Three Lions (detail), Large Parade Fibula (rear chamber, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, Cerveteri), 670–650 B.C.E., gold, 29.2 cm long (Museo Gregoriano Etrusco, Musei Vaticani) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The interconnectedness of the ancient Mediterranean world

The material culture of the Mediterranean basin in the seventh century B.C.E. affords us a glimpse of a dynamic and increasingly interconnected world. This Proto-Archaic phase of the Mediterranean world (also sometimes still referred to as the “Orientalizing” period) offers evidence of techniques—and possibly even artists and makers themselves—transmitted and transported from one region to another. Funereal architecture and associated material objects deposited in tombs, often referred to as “grave goods,” provide important indications about contemporary customs, materials, and monuments and serve as revealing indicators of the priorities and preferences of a culture.

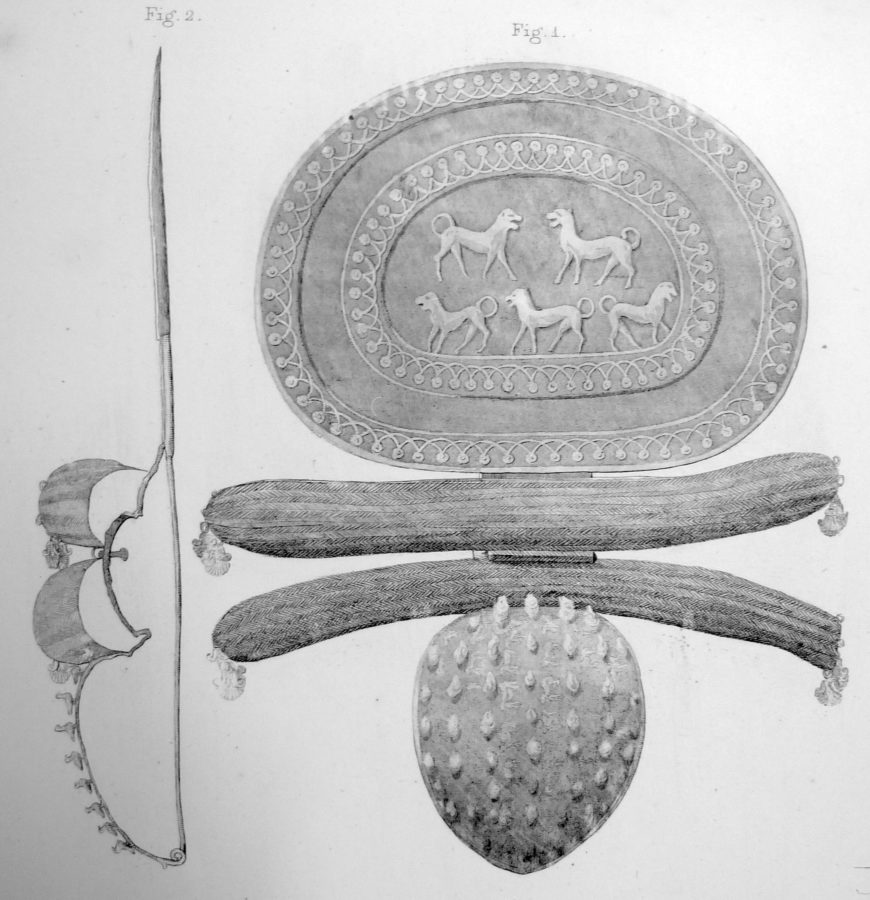

Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675–650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut, and granulated (Museo Gregoriano Etrusco, Musei Vaticani) (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An Etruscan tomb

In 1836 an Etruscan tomb located in the Sorbo necropolis of ancient Caere (now Cerveteri, Italy) was opened and its contents revealed. The tomb was of the tumulus-type, meaning a tomb covered with a mound of earth, and was of the sort used by the members of the social elite of the Etruscan culture. The seventh-century B.C.E. tomb had remained intact and undisturbed since antiquity (a fortuitous circumstance since such tombs are frequently discovered in a disturbed or looted state).

Detail, Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675–650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut and granulated (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The funereal objects (now in the Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums), demonstrate how objects and materials can communicate messages about a person’s social or economic status. The the assemblage of objects in the Regolini-Galassi tomb represents a broad geographic range and an aesthetic that indicates the influence of the ancient Near East. This is especially evident in metal-working techniques used to produce objects in the tomb and, in the broader landscape of funereal culture, objects either imported from the Near East or manufactured by Near Eastern craftspeople for elite consumption (such as their use as grave goods). Social elites not only desired to own and display such objects but also used them to reinforce their status and that of their family. The conspicuous deposition of these objects in the tomb would indicate to viewers or onlookers that not only was the deceased an important person but also that her surviving family members were important people in the community. In this way, the objects themselves facilitate a conversation about wealth and status among the Etruscans.

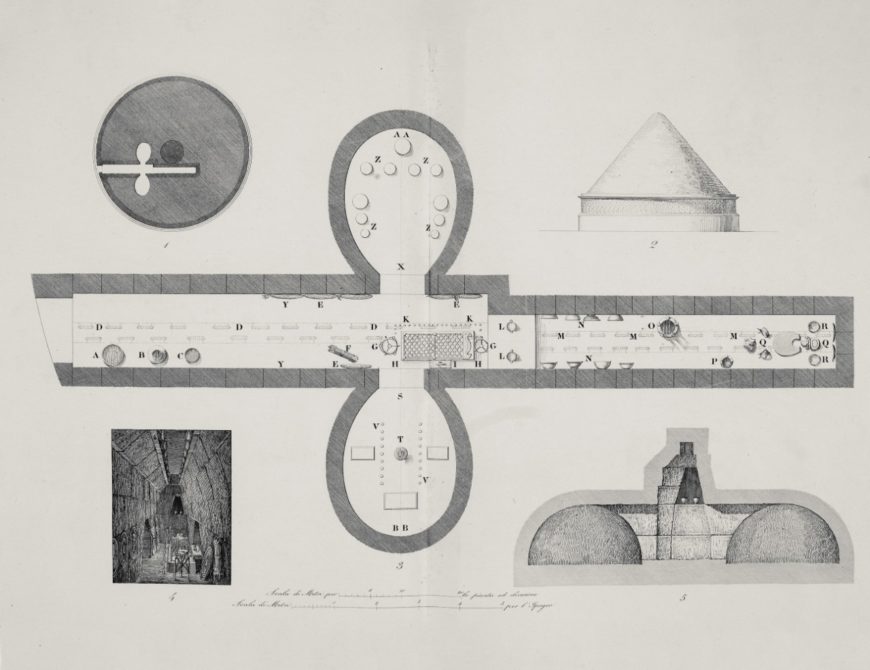

The architecture of the tomb and its context

The explorers of the tomb—General Vincenzo Galassi, a military officer, and Alessandro Regolini, the archpriest of Cerveteri—discovered that the tomb’s primary occupant was an adult female and that, judging both by the tomb architecture and the grave goods, she would have numbered among the social elite of ancient Caere.

The tomb is monumental in scale and was partially carved from the tuff bedrock of Caere. The tomb is approached by a short, narrow dromos and is composed of a 37-meter long corridor off of which two side chambers open. A corbelled vault covers the dromos. The exterior of the tomb was covered by an initial mound of earth known as a tumulus that measured some 46 meters in diameter; a second tumulus covered the tomb in the sixth century B.C.E. when additional tombs were added.

Once built, the tomb was stocked with grave goods to accompany the descendants; no fewer than 327 objects have been recorded. Many of these objects were manufactured of precious metals, including a significant quantity of gold. The tomb’s side chambers were used, respectively, for storage and the burial of a cremated male. The closed chamber at the end of the lateral corridor contained the principal burial, that of an elite female, and the majority of the grave goods (no. 1 to 226 in Pareti’s documentation). Some of the grave objects are inscribed mi larthia, meaning “I am the property of Larth.” This suggests that Larth, being a male, is the father of the deceased woman. Additional epigraphic evidence has led to the identification of the woman herself as one Larthia Velthurus. The parade fibula was found associated with this female burial, although precise documentation of the findspot is unclear since the tomb’s opening predates modern archaeology. The conventional date for the tomb and its contents is c. 675 to 650 B.C.E., although some scholars will move the date forward to the 640s B.C.E.

Regolini-Galassi Tomb plan (image: Vatican Museums)

The so-called Parade Fibula and its design

The so-called parade fibula itself measures 31.5 cm high by 24.4 cm thick; the disc ranges in thickness from 0.11 to 0.19 mm. The fibula weighs 173 grams (6.1024 ounces). While a normal-sized fibula would have functioned as a pin to fasten garments together (much like a modern safety pin operates), the functionality of this example, given its size and splendor, has long been debated. It is possible that this example was prepared especially as a grave offering for the deceased female.

Scholars have debated the function of the parade fibula since the tomb’s discovery. Various theories have been proposed, including that the fibula could have been displayed as a sort of headdress (and so not a fibula at all?), including one that imagines it positioned atop the face and forehead of the decedent. Most interpretations pair the fibula with the so-called gold pectoral from the same tomb that similarly demonstrates the influence of Near Eastern metal-working techniques and geometric patterns.

Three elements make up the so-called parade fibula. These are, from bottom to top, an oval-shaped, arched element, a flat semi-circular disc, and a pair of transverse, hollow cylinders that are attached to the other elements by a hinge. A long pin is attached to the back of the fibula.

Decorative techniques

Detail, Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675-650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut and granulated (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Fibula decorated with zigzag lines and incised labyrinths (Proto-Etruscan), c. 825–775 B.C.E., gold, 7.4 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

The techniques that were used to decorate the surface of the fibula are indicative of artistic trends and technologies originating in the ancient Near East that were overspreading the Mediterranean basin. These techniques—granulation, filigree, and repoussé —all originated in the east, with granulation appearing in tombs at Ur in Mesopotamia by c. 2500 B.C.E. The granulation technique is attested in Etruria beginning in the middle of the eighth century B.C.E.

The decorative motifs that reference the afterlife, including the presence of the Egyptian goddess Hathor seem to confirm the fibula’s funeral function. Hathor is visible on the terminus of the lower element of the fibula. Although the Regolini-Galassi parade fibula is unique, it finds comparison with other contemporary disc fibulae such as the one in the collection of The British Museum.

Five lions (detail), Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675-650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut and granulated (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A group of five lions occupies the center of the semicircular disc of the fibula. These lions were made by the use of stamps and then attached to the disc of the fibula. A border achieved with the granulation technique frames the lions. The surface of the horizontal tubular elements are covered with granulation, while the lower ovoid element includes patterns like a frieze of griffins that indicates the influence of the ancient Near East. The composition of the iconography of the fibula stresses elite themes and status, since an item of foreign manufacture that reinforces royal icons reinforces the status and activities of social elites and the behaviors they used to maintain their position. Ritual themes are important as well and, overall, the group of grave goods represents the outlook of Mediterranean social elites of the Proto-Archaic period.

Frieze of griffins (detail), Large Parade Fibula, Cerveteri, Regolini-Galassi Tomb, from the main tomb in the lower chamber, 675-650 B.C., gold: embossed, punched, cut and granulated (Gregorian Etruscan Museum of the Vatican Museums) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A world increasingly connected

The iconographic motifs (the griffins and lions) of the parade fibula speaks to the influence of the ancient Near East and possibly even to manufacture by artisans from Syro-Palestine.

Taken as part of the larger assemblage of artifacts, the fibula speaks volumes about the needs of Etruscan elites in the seventh century B.C.E. These elites felt it necessary to communicate and reinforce their own socio-economic status by accumulating and displaying certain types of objects that matched their apparent status. Not only were many of these objects crafted from intrinsically valuable materials like gold they also had the appeal of being examples of imported and exotic items. Similar items likely were to be found in the homes and tombs of the social peers of the occupants of the Regolini-Galassi tomb, as proto-archaic elites jockeyed for position and used objects and materials acquired by means of long-distance supply chains to signal their primacy and relevance in a world that was increasingly interlinked and moving ever more quickly.

Additional resources

Large Parade Fibula, Musei Vaticani, Large parade Fibula (Vatican Museum)

Etruscanning: digital encounters with the Regolini-Galassi Tomb with blog posts.

Massimo Botto and Alessandro Naso, eds. Caere orientalizzante: nuove ricerche su città e necropoli (Studia Caeretana; 1) (Rome: CNR, Istituto di studi sul Mediterraneo antico; Paris: Musée du Louvre, Département des antiquités grecques, étrusques et romaines, 2018).

Francesco Buranelli and Maurizio Sannibale, “Non piu solo ‘Larthia’. Un documento epigrafico inedito dalla Tomba Regolini-Galassi di Caere,” in Aei mnestos: miscellanea i studi per Mauro Cristofani, edited by B. Adembri (Florence: Centro Di, 2005) pp. 220-31..

Richard Daniel De Puma, “Ch. 18. Gold and Ivory,” in Caere, edited by Nancy Thomson de Grummond and Lisa C. Pieraccini (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016), pp. 195–208.

Adriana Emiliozzi, “La tomba Regolini-Galassi e i suoi carri.” in Caere orientalizzante: nuove ricerche su città e necropoli, edited by Alessandro Naso and Massimo Botto (Rome; Paris: CNR Istituto di studi sul Mediterraneo antico, 2018), pp. 195–304.

F. W. v. Hase, “The ceremonial jewellery from the Regolini-Galassi tomb in Cerveteri: Some ideas concerning the workshop,” in Prehistoric Gold in Europe: Mines, Metallurgy and Manufacture, edited by Giulio Morteani and Jeremy P. Northover (Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995) pp. 533–559.

Tamar Hodos, The Archaeology of the Mediterranean Iron Age: A Globalising World c.1100–600 B.C.E. (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Luigi Pareti, La tomba Regolini-Galassi del Museo gregoriano etrusco e la civiltà dell’Italia centrale nel sec. VII a.C. (Vatican City: Tip. poliglotta vaticana, 1947).

Elfriede Paschinger, “Über ein mögliches familiäres Verhältnis der in der Tomba Regolini — Galassi bestatteten Personen,” Antike Welt, vol. 24, no. 2 (1993), pp. 111–124

Ingrid Pohl, The Iron Age Necropolis of Sorbo at Cerveteri (Skrifter utgivna av Svenska Institutet i Rom; 4,32.) (Stockholm: Svenska Institutet i Rom, 1972).

Christie A. Ray, “Natural interaction in VR environments for cultural heritage: the virtual reconstruction of the Regolini-Galassi tomb in Cerveteri,” in Archeologia e calcolatori 24 (2013) pp. 231-247.

Christie A. Ray, J. Vos, and P. Retèl, Etruscanning: Digital Encounters with the Regolini-Galassi Tomb (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum, 2013).

Laura Maria Russo, “Dalla Tomba Regolini Galassi alle hydrie ceretane: il ruolo di Cerveteri nell’assimilazione del bestiario fantastico orientalizzante in Etruria,” in Nuovi studi sul bestiario fantastico di età orientalizzante nella penisola italiana (Trento: Tangram Edizioni Scientifiche, 2015) pp. 275–302.

Maurizio Sannibale, “Gli ori della Tomba Regolini-Galassi: tra tecnologia e simbolo. Nuove proposte di lettura nel quadro del fenomeno orientalizzante in Etruria.” Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome 120,2 (2008) pp. 337–367.

Maurizio Sannibale, “Iconografie e simboli orientali nelle corti dei principi etruschi,” Byrsa 7, 1 / 2 (2008), pp. 85–123.

Maurizio Sannibale, “Orientalizing Etruria,” in The Etruscan World, edited by Jean MacIntosh Turfa (London: Routledge, 2014). pp. 99–133.

Jean MacIntosh Turfa, “Ch. 3. International contacts: commerce, trade, and foreign affairs,” Etruscan life and afterlife: a handbook of Etruscan studies, edited by Larissa Bonfante (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1986) pp. 66–91.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”vatfib,”]