Forget what you know about Greek and Roman architectural orders—Etruscans had their own unique style.

Apulu (Apollo of Veii), from the roof of the Portonaccio temple, Italy, c. 510–500 B.C.E., painted terracotta, 5′ 11″ high (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome)

Reconstruction of an Etruscan Temple of the 6th century according to Vitruvius (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Etruscan temples have largely vanished

Among the early Etruscans, the worship of the Gods and Goddesses did not take place in or around monumental temples as it did in early Greece or in the Ancient Near East, but rather, in nature. Early Etruscans created ritual spaces in groves and enclosures open to the sky with sacred boundaries carefully marked through ritual ceremony.

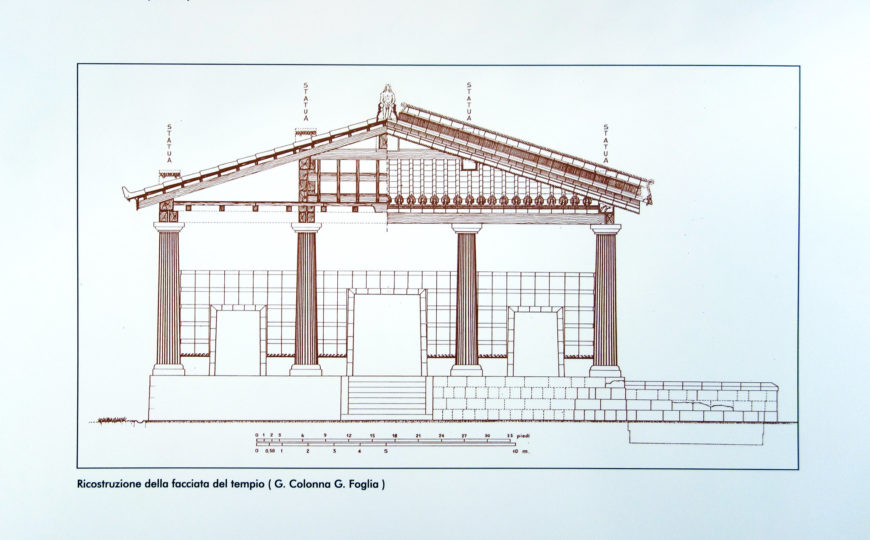

Around 600 B.C.E., however, the desire to create monumental structures for the gods spread throughout Etruria, most likely as a result of Greek influence. While the desire to create temples for the gods may have been inspired by contact with Greek culture, Etruscan religious architecture was markedly different in material and design. These colorful and ornate structures typically had stone foundations but their wood, mud-brick and terracotta superstructures suffered far more from exposure to the elements. Greek temples still survive today in parts of Greece and southern Italy since they were constructed of stone and marble but Etruscan temples were built with mostly ephemeral materials and have largely vanished.

How do we know what they looked like?

Despite the comparatively short-lived nature of Etruscan religious structures, Etruscan temple design had a huge impact on Renaissance architecture and one can see echoes of Etruscan, or ‘Tuscan,’ columns (doric columns with bases) in many buildings of the Renaissance and later in Italy. But if the temples weren’t around during the 15th and 16th centuries, how did Renaissance builders know what they looked like and, for that matter, how do we know what they looked like?

Fortunately, an ancient Roman architect by the name of Vitruvius wrote about Etruscan temples in his book De architectura in the late first century B.C.E. In his treatise on ancient architecture, Vitruvius described the key elements of Etruscan temples and it was his description that inspired Renaissance architects to return to the roots of Tuscan design and allows archaeologists and art historians today to recreate the appearance of these buildings.

Archaeological evidence for the Temple of Minerva

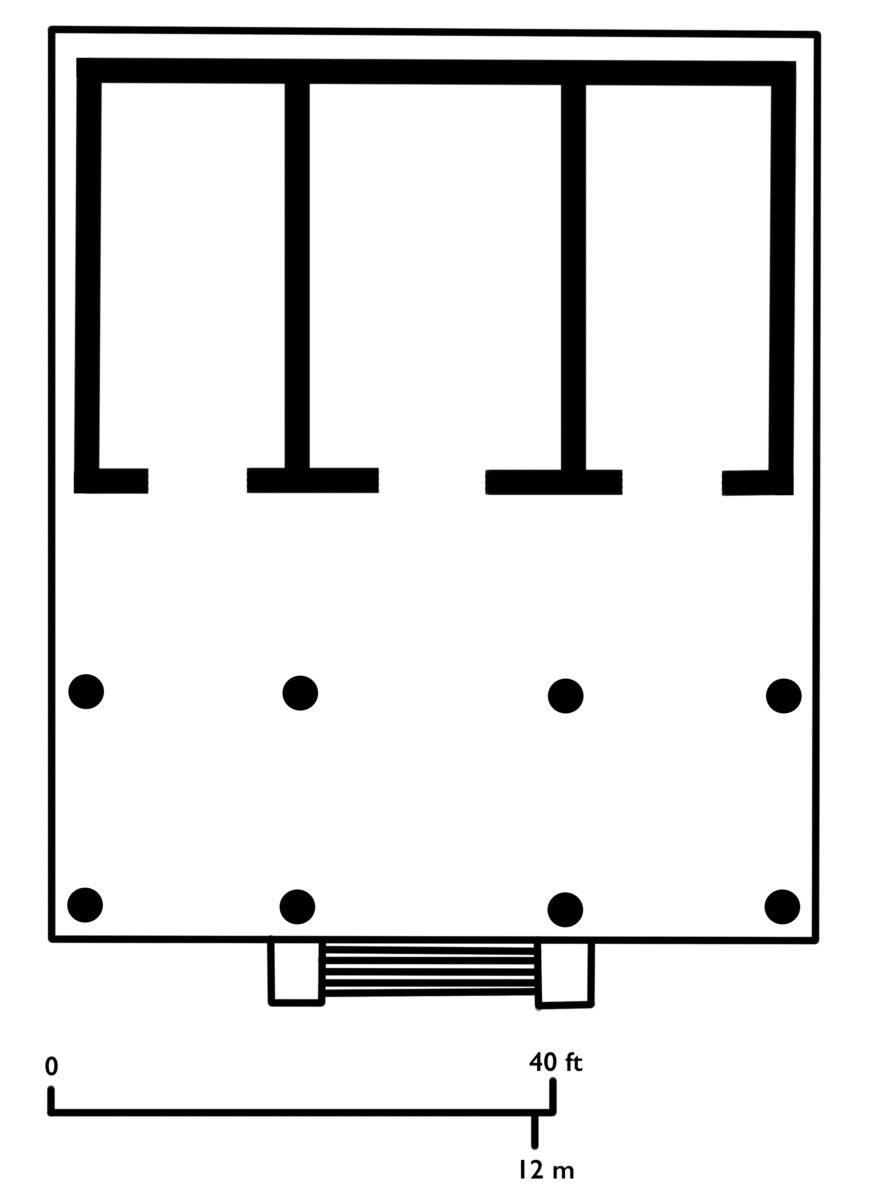

The archaeological evidence that does remain from many Etruscan temples largely confirms Vitruvius’s description. One of the best explored and known of these is the Portonaccio Temple dedicated to the goddess Minerva (Roman=Minerva/Greek=Athena) at the city of Veii about 18 km north of Rome. The tufa-block foundations of the Portonaccio temple still remain and their nearly square footprint reflects Vitruvius’s description of a floor plan with proportions that are 5:6, just a bit deeper than wide.

The temple is also roughly divided into two parts—a deep front porch with widely-spaced Tuscan columns and a back portion divided into three separate rooms. Known as a triple cella, this three room configuration seems to reflect a divine triad associated with the temple, perhaps Menrva as well as Tinia (Jupiter/Zeus) and Uni (Juno/Hera).

In addition to their internal organization and materials, what also made Etruscan temples noticeably distinct from Greek ones was a high podium and frontal entrance. Approaching the Parthenon with its low rising stepped entrance and encircling forest of columns would have been a very different experience from approaching an Etruscan temple high off the ground with a single, defined entrance.

Reconstruction of an Etruscan Temple of the 6th century according to Vitruvius identifying placement of terracotta sculpture (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Sculpture

Perhaps most interesting about the Portonaccio temple is the abundant terracotta sculpture that still remains, the volume and quality of which is without parallel in Etruria. In addition to many terracotta architectural elements (masks, antefixes, decorative details), a series of over life-size terracotta sculptures have also been discovered in association with the temple. Originally placed on the ridge of temple roof, these figures seem to be Etruscan assimilations of Greek gods, set up as a tableau to enact some mythic event.

Detail, Aplu (Apollo of Veii), from the roof of the Portonaccio Temple, Veii, Italy, c. 510–500 B.C.E., painted terracotta, 5 feet 11 inches high (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Aplu (Apollo of Veii), from the roof of the Portonaccio Temple, Veii, Italy, c. 510–500 B.C.E., painted terracotta, 5 feet 11 inches high (Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Apollo of Veii

The most famous and well-preserved of these is the Aplu (Apollo of Veii), a dynamic, striding masterpiece of large scale terracotta sculpture and likely a central figure in the rooftop narrative. His counterpart may have been the less well-preserved figure of Hercle (Hercules) with whom he struggled in an epic contest over the Golden Hind, an enormous deer sacred to Apollo’s twin sister Artemis. Other figures discovered with these suggest an audience watching the action. Whatever the myth may have been, it was a completely Etruscan innovation to use sculpture in this way, placed at the peak of the temple roof—creating what must have been an impressive tableau against the backdrop of the sky.

An artist by the name of Vulca?

Since Etruscan art is almost entirely anonymous it is impossible to know who may have contributed to such innovative display strategies. We may, however, know the name of the artist associated with the workshop that produced the terracotta sculpture. Centuries after these pieces were created, the Roman writer Pliny recorded that in the late 6th century B.C.E., an Etruscan artist by the name of Vulca was summoned from Veii to Rome to decorate the most important temple there, the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. The technical knowledge required to produce terracotta sculpture at such a large scale was considerable and it may just have been the master sculptor Vulca whose skill at the Portonaccio temple earned him not only a prestigious commission in Rome but a place in the history books as well.

Additional resources

This sculpture at the Villa Guila, Rome

Apollo de Veio and its 2004 restoration

Etruscan art on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”Portonaccio Temple,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:04] The ancient Etruscans built temples that in some ways look like Greek and Roman temples but are also distinct.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:12] When we look at them from the front, they certainly look like ancient Greek temples, but they’re really different.

Dr. Zucker: [0:18] For one thing, the Etruscans did not use the Greek orders, that is, Doric or Ionic or Corinthian. For another, they had very deep porches, and the temples tended to be more square.

Dr. Harris: [0:28] And they’re not made of stone the way ancient Greek temples were.

Dr. Zucker: [0:31] We’re looking at the fragments of four large-scale terracotta figures from the temple at Veii, which was a principal city of the Etruscans, and we’re seeing them in the Etruscan Museum in Rome.

Dr. Harris: [0:42] In ancient Greek architecture, we might expect to see figures like this occupy the pediment, but instead these figures lined the rooftop.

Dr. Zucker: [0:51] Like ancient Greek sculpture, they were very highly painted.

Dr. Harris: [0:55] It’s such an interesting moment in Italy in the 6th century [B.C.E]. We have Greek colonies in the south of Italy. We have the Romans in Rome, although ruled by Etruscan kings. Then, up in the northern part of Italy, we have a confederacy of about a dozen Etruscan city-states. Italy is a complicated place in the 6th century B.C.E.

Dr. Zucker: [1:14] These are slightly larger than life. Although they were placed equidistantly, they do enact a specific scene.

Dr. Harris: [1:20] This is a scene from ancient Greek mythology. It’s the third labor of Hercules. Hercules is sent out to capture a very large deer with golden horns. Now, this deer is very special to the goddess Artemis. Actually, the idea is that the person who sent Hercules on this labor wants to annoy Artemis.

Dr. Zucker: [1:39] So that she punishes Hercules. Now, Hercules is known in the original Greek as Herakles. He’s shown here with the golden hind under him. He has been able to capture it. Now, he’s being confronted by both Artemis and her brother, Apollo.

Dr. Harris: [1:53] They want the deer back.

Dr. Zucker: [1:55] Hercules promises to release it once he shows it to the king who sent him on this labor.

Dr. Harris: [2:00] Something we find in Etruscan sculpture is this sense of movement and liveliness. We see that in the “Sarcophagus of the Spouses,” for example. We see that here with the figure of Apollo, who is striding forward, and Hercules, too, whose body is leaning forward and whose knee is raised. We see that sense of musculature and animation.

Dr. Zucker: [2:22] These are terracotta, that is, they’re clay. They would’ve been modeled in an additive process.

Dr. Harris: [2:27] Apollo wears that Archaic smile that we’re used to seeing from the kouros figures, but he’s still very different than the Greek figures. His smile is a little bit more animated. His proportions of his body are different.

Dr. Zucker: [2:41] The look on his face is not one that is looking out into a generalized space. He is catching the eye of Hercules. He is engaged directly, and therefore engages us.

Dr. Harris: [2:52] Just like their faces are stylized, their bodies are also highly stylized. There’s almost a sense of twisting at the hips, and the shoulders are overly rounded and broad. This is not a naturalistic depiction of the body.

Dr. Zucker: [3:06] The artist seems to favor detail. For instance, look at the way that the drapery falls flat, creating these lovely little loops. Look at the marvelous detail of the feet.

[3:16] This is such a tease, because here we have this engaging, lively sculpture from a culture whose literature has been lost and who we know so little about.

[3:25] [music]