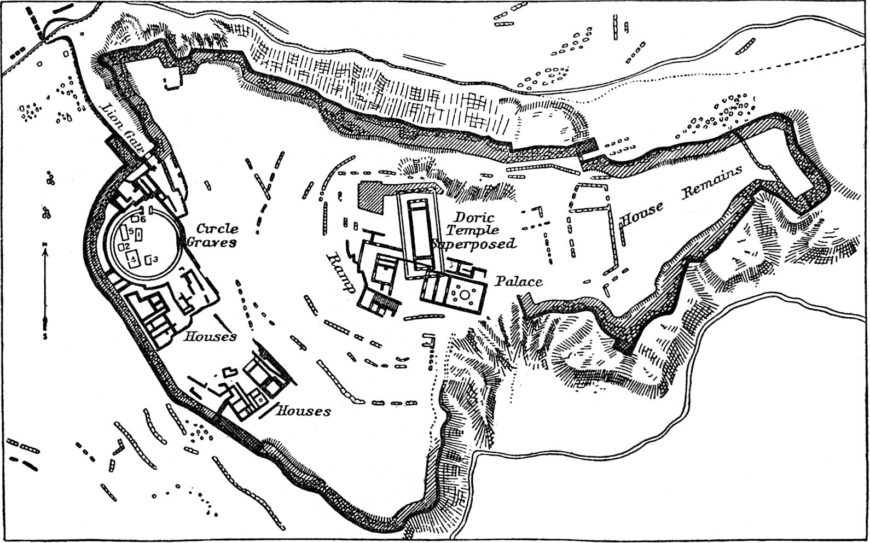

The ancient citadel (fortified city) at Mycenae is located on top of an isolated hill and provides truly spectacular views of the surrounding area, making it an ideal location for a defensive stronghold. Mycenaean culture dominated southern Greece, but is perhaps best known for the site of Mycenae itself, which includes the citadel (with a palace), and is surrounded by different forms of tombs and other structures. Mycenaean culture firmly establishes itself in the late Bronze Age, specifically, around 1600 B.C.E.

At around 1600 B.C.E.—seemingly out of nowhere—the shaft graves at the site of Mycenae are built. These are two circular walled plots containing graves, built some 50 years apart, close to the fortification wall of the citadel. Archaeologists named these “Grave Circle A” and “Grave Circle B.” Grave Circle B is earlier than A (but A was discovered first) and contained some 14 shaft graves with 24 burials; Grave Circle A held 6 shaft graves with 19 burials. These burials contained men, women, and children who were related to one another, recent DNA analysis has shown.

Mask of Agamemnon, from shaft grave V, Grave Circle A, Mycenae c.1550–1500 B.C.E., gold, 12″ / 35 cm (National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

More importantly, along with the burials one of the largest deposits of precious metals, especially gold (including the Mask of Agamemnon), ever found in ancient Greece was discovered. An even wealthier single shaft grave has been recently discovered near the Mycenaean palace at Pylos. The wealth of the shaft graves is shocking, a huge change from the earlier rather modest remains of Bronze Age mainland Greece, and initiates an era of Mycenaean activity and power which stretches across most of the region.

The focus sites of this era are Mycenaean palaces which all have several aspects in common: a central megaron or throne room with a large hearth which is adjacent to an open court, commanding views of an agricultural plane, colorful and often figural wall painting, and associations with grand burial structures such as tholoi (beehive tombs). These types of sites can be found not only at Mycenae but also at Tiryns, Iolkos, Orchomenos, Gla, Pylos, Thebes, and on the acropolis at Athens.

Written and visual records

We know a lot about the Mycenaeans because they left written records which can be read. They wrote in a script called Linear B (related to the early Minoan Linear A) which recorded an early form of the Classical Greek language. At the sites of Mycenae, Pylos, Tiryns, and Thebes clay tablets inscribed in Linear B have been found describing a theocratic administration, very similar to the one described in the Linear B tablets found at Knossos on Crete. A Wanax (the central figure of authority in Mycenaean society) presided over a complex religious and economic system which, at Pylos, was centered around a perfume oil and textile industry.

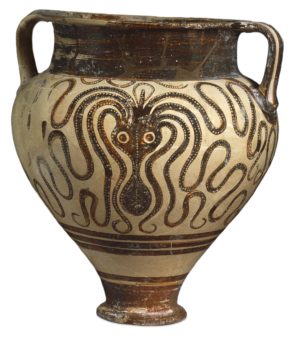

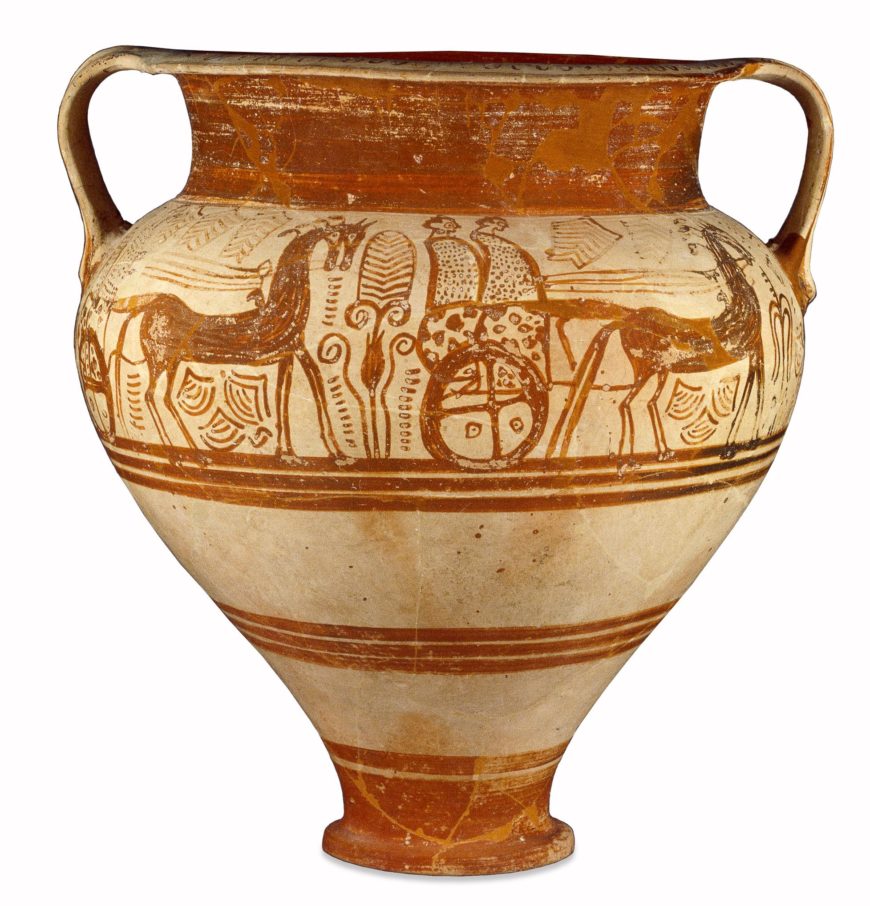

At that time there was regular contact and exchange between Mycenaean elite and the Pharaonic court in Egypt. Stirrup jars, the uniquely branded vessels of the wildly successful Mycenaean perfume oil trade, are found all over the Mediterranean basin. The design and decoration of Mycenaean pottery riffs off older Minoan styles in almost modernist abstractions and produces the first narrative pottery painting tradition in the ancient Greek world.

The motif of armed combat, hand-to-hand (parry and thrust), was perfected by Mycenaean artists, and can be seen beautifully represented in the minute scale of gem engraving.

Two warriors in hand-to-hand combat, Pylos Combat Agate, discovered in the Grave of the Griffin Warrior at Pylos, c. 1450 B.C.E., 1.5 inches wide

At the same time, Mycenaean architects and engineers embraced a massive scale with huge hydraulic projects, far-flung road works, and defensive walls so gigantic they never succumb to burial, remaining largely intact and providing the inspiration for mythological explication until the modern era.

Around 1200 B.C.E. nearly all major Mycenaean sites experienced massive destruction, the cause of which is unclear. Many sites were quickly reinhabited, but the elite areas, such as the spaces where it is believed the Wanax ruled, were not rebuilt. For the next 50 to 75 years, pottery production and even wall painting continues but becomes less fine and increasingly regional, eventually ceasing all together. Burial practice changes as well, from shaft graves to small individual cist graves (small below-ground stone boxes) containing cremated remains.By 1050 B.C.E., at the end of the Bronze Age, the Greek world (the Cycladic islands, Crete, and the Mainland), have only memories left of the once wealthy and far reaching polities which had ruled for nearly a millennium, an era soon to be beautifully enshrined in the oral epic tradition of Homer.

Additional resources

Mycenaean culture on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Archaeological Sites of Mycenae and Tiryns (UNESCO)