The Cleveland Apollo, c. 350–200 B.C.E., bronze, 1.5 m high (The Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Matching text to image

The Roman author Pliny the Elder finished writing Natural History, an encyclopedia of information about all aspects of the ancient world, in the 1st century C.E. In his discussion of Greek sculptors, Pliny mentions the famous Praxiteles, writing that “although [he was] more successful and therefore more celebrated in marble, nevertheless [he] also made some very beautiful works in bronze: […].” [1] Pliny then provides a list of Praxiteles’s bronze sculptures. Among them is a statue of the Greek god Apollo:

“Praxiteles also made a youthful Apollo called in Greek the Lizard-Slayer [Sauroktonos] because he is waiting with an arrow for a lizard creeping towards him.”Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 34.69, translated by H. Rackham

In the centuries since Pliny wrote his Natural History, many Roman marble copies of Praxiteles’s bronze Apollo Sauroktonos have been discovered. Art historians studied these marble copies closely to understand what they can tell us about Praxiteles’s style and the original they imitate. But these copies were made centuries after Praxiteles crafted his Apollo Sauroktonos, in an entirely different material, for an entirely different audience. While the Roman marble copies provide a general sense of what the original Apollo Sauroktonos looked like, they are distant from it.

The Cleveland Apollo, c. 350–200 B.C.E., bronze, 1.5 m high (The Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

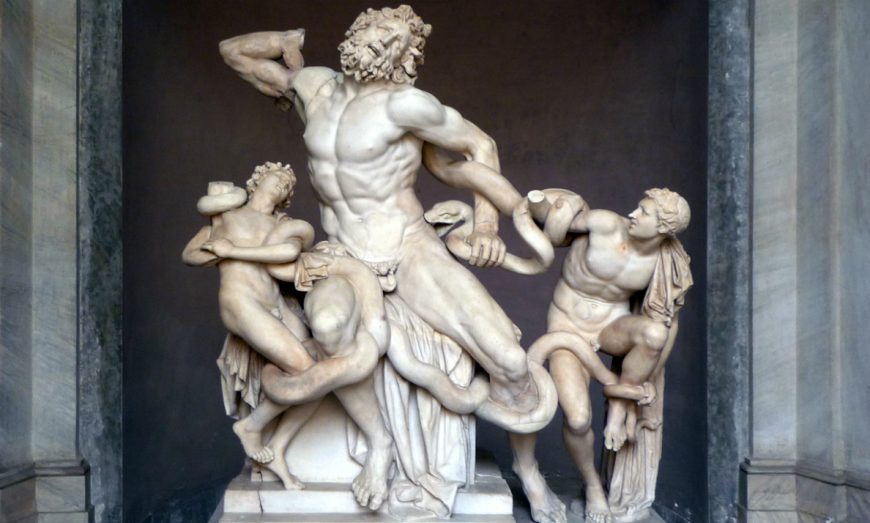

Our understanding of the Apollo Sauroktonos changed in 2003, when a controversial bronze sculpture was put up for sale by an art dealer in Switzerland. The statue had no real provenience, suggesting that it may have been illegally removed from its original context. Some scholars objected to its sale because of its murky origins. Despite these objections, the Cleveland Museum of Art purchased the statue. Their curators and conservators studied it closely and initially concluded that it was not just a Greek original, but in fact the original Apollo made by Praxiteles himself. While the statue is not perfectly preserved, the male figure can be reconstructed as leaning against a tree and perhaps holding an arrow that he points towards a lizard crawling up the tree’s trunk. The tree does not survive, but the lizard does, and is displayed along with the male figure at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Lizard-like creature from The Cleveland Apollo, c. 350–200 B.C.E., bronze, 14.8 cm (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

Not everyone has accepted the Cleveland Museum’s conclusion that this statue is an original by Praxiteles. Scholars continue to debate whether it is really Praxiteles’s work to this day. Even the Cleveland Museum now presents the statue in more nuanced terms, stating that it may be either by Praxiteles or a follower. In this essay, we will take a closer look at this statue to answer some of the most important questions it raises. What is Praxiteles’s style, and does this sculpture match it? Does it resemble other sculptures made during the Late Classical period in Greece? What do scientific analyses reveal about its origins? And finally, if this is not an original by Praxiteles, what is it?

Rear view of the Cleveland Apollo, c. 350–200 B.C.E., bronze, 1.5 m high (The Cleveland Museum of Art)

Praxiteles’s style

Praxiteles was a Greek sculptor who worked in the middle of the 4th century B.C.E., probably between 375 and 335. [2] The most celebrated of his many famous sculptures was the Aphrodite of Knidos, the first life size ancient Greek sculpture of a nude female. None of Praxiteles’s original work survives (except, perhaps, the Apollo now in Cleveland). Despite this, we have a good sense of Praxiteles’s typical style from the many Roman copies of his work and literary descriptions of the originals.

The main characteristics of Praxiteles’s style are visible in the bronze sculpture in Cleveland. The male figure leans forwards and far to his left. In fact, he bends so far to the side that he must have originally leaned on a support to keep himself upright. This leaning posture results in the figure’s body resembling an S, positioning him in what is often called the “Praxitelean S curve” because it is so typical of Praxiteles’s figures. [3] Another typical Praxitelean trait evident in this sculpture is the smoothness of the muscles, which seem almost underdeveloped. [4] The male figure is presented as a boy, not a fully grown adult man. This somewhat androgynous portrayal of a young male was characteristic of Praxiteles.

Head (detail), The Cleveland Apollo, c. 350–200 B.C.E., bronze, 1.5 m high (The Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

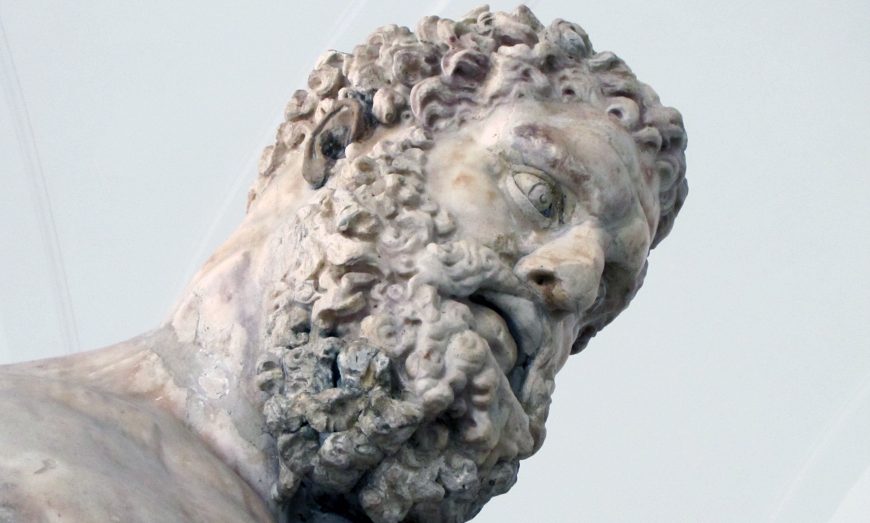

The bronze statue’s head and face also seem typical of Praxiteles’s style as we understand it today. The boy has an elaborate hairstyle which is partially held back by a headband. His eyes are inlaid with stone and his lips are inlaid with copper, making him appear more lifelike. [5] He has a dreamy expression that is intensified by his bright white eyes. He gazes down, likely towards the lizard that climbed up the now-missing tree he once leaned on, without much emotion. Many of Praxiteles’s figures have this kind of detachment.

Our understanding of Praxiteles’s sculptural style is somewhat limited because we can only study it through Roman marble copies and written descriptions. However, what we know of it matches well with the style of the statue in Cleveland.

Late Classical style and Roman imitations

The Cleveland bronze also has traits that are typical of the Late Classical style more broadly. Late Classical sculptors had a particular interest in showing Greek gods in intimate moments that make them appear almost approachable. This interest is evident in Praxiteles’s portrayal of Apollo. In order to better envision what the statue originally looked like, we can look at a Roman marble copy that preserves a portion of the tree trunk the god leans on and the lizard climbing up it.

Praxiteles, Apollo Sauroktonos, Roman marble copy of a Greek bronze original from c. 350 B.C.E., 1.67 m high (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

The best preserved Roman copy of the Apollo Sauroktonos is in the Louvre. [6] Apollo leans far to the left, his elbow on a tree trunk. Almost all of his weight is on his right leg while his left leg remains free, its heel raised up from the ground. This pushes Apollo’s right hip outwards into the Praxitelean S curve posture. His gaze is directed towards the lizard climbing up the tree. If we accept Pliny’s description of the Apollo Sauroktonos, we can imagine Apollo holding an arrow in his right hand. His left hand is also positioned as if it was holding something, perhaps a cord tethered to the lizard. [7]

Praxiteles, Apollo Sauroktonos, Roman marble copy of a Greek bronze original from c. 350 B.C.E., 1.53 m high (Pio Clementino Museum, Vatican City; photo: Fabrizio Garrisi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Another Roman replica shows Apollo in nearly the exact same posture. Once again, the god’s attentive, downwards gaze draws us into the scene represented. [8] But what is actually going on here? Pliny describes Apollo as a “Lizard-Slayer,” but there is no aggression in his gaze. He seems to be teasing the lizard rather than preparing to kill it. [9] The moment is calm. Some scholars believe that this is a representation of an important moment in Apollo’s childhood, when he killed a monstrous snake named Python that was living at Delphi in order to make room for the construction of his own famous sanctuary on the site. [10] But other scholars point out that Apollo Sauroktonos is looking towards a lizard, not a snake, and not a very monstrous lizard at that. [11] They do not accept that this is a representation of such an important battle in Apollo’s life. [12] Although the sculpture seems to embody the Late Classical tendency to show gods in everyday moments, its precise meaning remains unknown.

Roman gem engraved with Apollo Sauroktonos, c. 1st–3rd century C.E., plasma, 1.4 x 1 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Moreover, the many Roman copies of the Apollo Sauroktonos suggest that this kind of intimate portrayal of the Greek god appealed to a Roman audience long after the end of the Greek Late Classical period. Roman artists replicated the Apollo Sauroktonos in marble statues and in smaller scale artworks, like the carved gem pictured above. The image may have been popular amongst the Romans because it represents a beautiful, androgynous young boy in the smooth Late Classical style, not because it was believed to carry any particular religious significance. [13]

In sum, although the Apollo Sauroktonos has many stylistic traits typical of the Late Classical period, these traits were appreciated and imitated long after the Late Classical period ended. We cannot rely on their presence to definitively identify the bronze in Cleveland as a Late Classical Greek original by Praxiteles.

The Cleveland Apollo, c. 350–200 B.C.E., bronze, 1.5 m high (The Cleveland Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Scientific analyses

Scientific analyses of the bronze in Cleveland have shed some more light on its possible origins but have not completely answered the question of when it was made. All of its metal pieces belong together, though its base might be slightly newer than the rest of it. [14] It seems to have undergone two major periods of weathering, the first very long and the second relatively short. [15] It was made in pieces using the indirect lost-wax casting technique, a process employed by many ancient sculptors. [16] These technical assessments of the sculpture do not disprove that the bronze sculpture in Cleveland was made in the 4th century B.C.E., but they don’t definitively confirm its ancient origins, either. We can never be sure of how advanced forgers’ work has become. Until we develop more advanced scientific technologies or discover more information about the statue’s original context, we cannot be sure that it was made by Praxiteles, or in the Late Classical period.

The problem of the “original”

While some scholars accept the bronze statue in Cleveland as Praxiteles’s original Apollo Sauroktonos, others are more hesitant. [17] The statue undoubtedly uses some Praxitelean stylistic features, including the S curve posture, smooth androgyny, and detached gaze. Its depiction of a god (if this is indeed Apollo) in an intimate moment is typical of the Late Classical period more broadly. But the image took on a life of its own in ancient Rome, where it was repeatedly replicated. The difficulties with identifying this statue as an original reflect some of the problems that arise when we only have literary descriptions and Roman imitations to guide our search for a missing Greek sculpture. We can’t be sure that this statue is the Apollo Sauroktonos described by Pliny the Elder, but we can still appreciate it as a remarkable artwork in its own right.