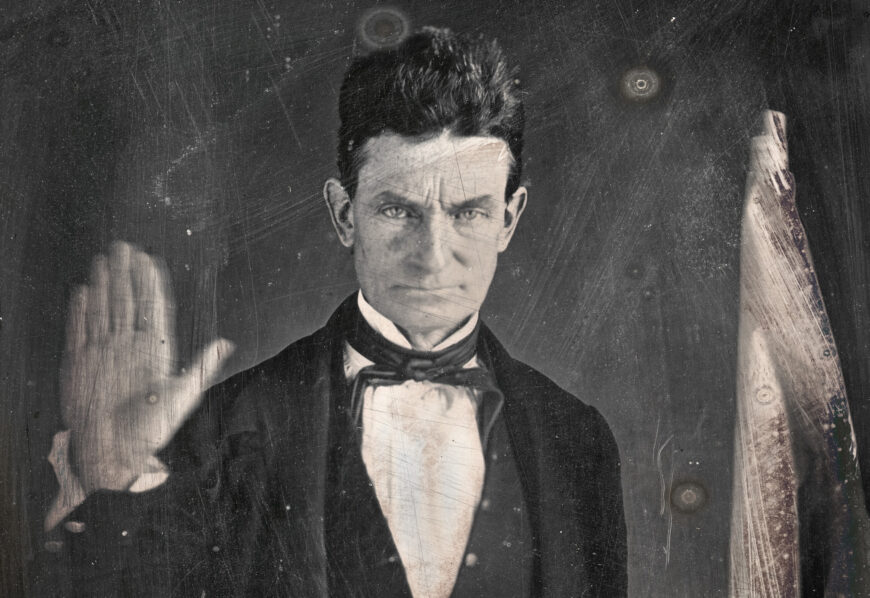

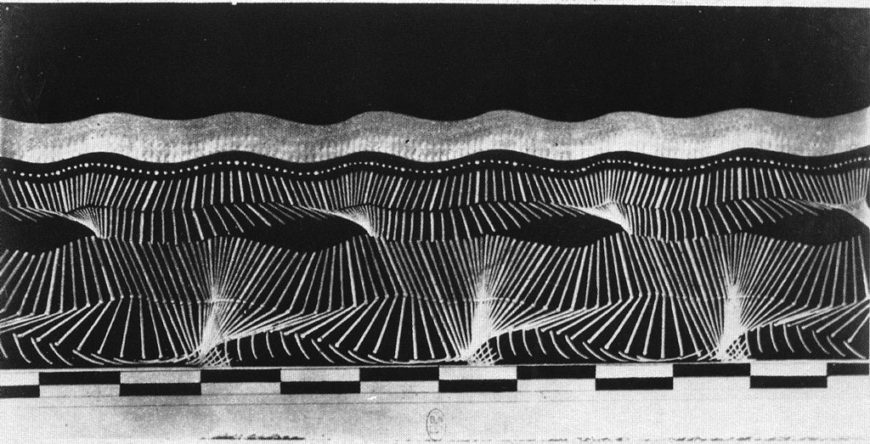

Étienne-Jules Marey, Joinville Soldier Walking, 1883, geometric chronophotograph (Paris College de France)

A series of slanted gray lines and a row of dots appear against a black background in wavy bands that reach the side edges of the picture plane. A thick gray stripe undulates along the top. The title of the photograph, Joinville Soldier Walking, suggests that this image of lines and dots in wavy bands represents a walking soldier. But how?

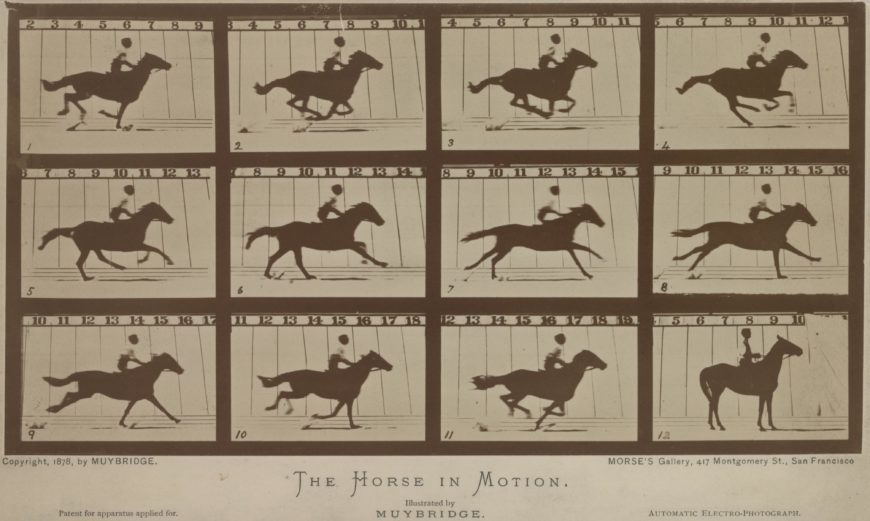

After seeing the publication of photographs of moving horses by Eadweard Muybridge in periodicals in 1878, French physiologist/medical doctor/biomechanics engineer Étienne-Jules Marey looked to photography as a tool for graphing the movement of objects across space and time, for later scientific analysis.

Eadweard Muybridge, gravure of Horse in Motion, published in La Nature (Dec. 1878). Muybridge’s published images often (but not always) featured sequential images of the same subject. For example, the bottom right corner image of Horse in Motion was spliced into the series, and was not from a photograph made 1/1000th-of-a-second after the image directly to its left. Unlike Marey, who sought scientific precision in photography, Muybridge’s chief concern was giving closure to the horse’s run. (Library of Congress)

Muybridge’s published images often (but not always) featured sequential images of the same subject. For example, the bottom right corner image of Horse in Motion was spliced into the series, and was not from a photograph made 1/1000th-of-a-second after the image directly to its left. Unlike Marey, who sought scientific precision in photography, Muybridge’s chief concern was giving closure to the horse’s run.

Photography, Marey noted, could halt thin slices of time’s passage, and these “atomized” views that surpassed the sensitivity of unaided human vision might prove useful for analyzing the mechanics of human and animal movement. [1] Marey’s goal, like that of other late-nineteenth-century motion photographers such as Muybridge, was to find a new understanding of time—a universal experience, but also one that is impossibly fleeting and elusive even as its passage is felt, and its effects apparent all around us. Making lasting images of the mechanics of moving bodies, Marey hoped, would lead to a better understanding of human locomotion. This might allow for the greater efficiency of body mechanics, in order to maximize both human movement and time.

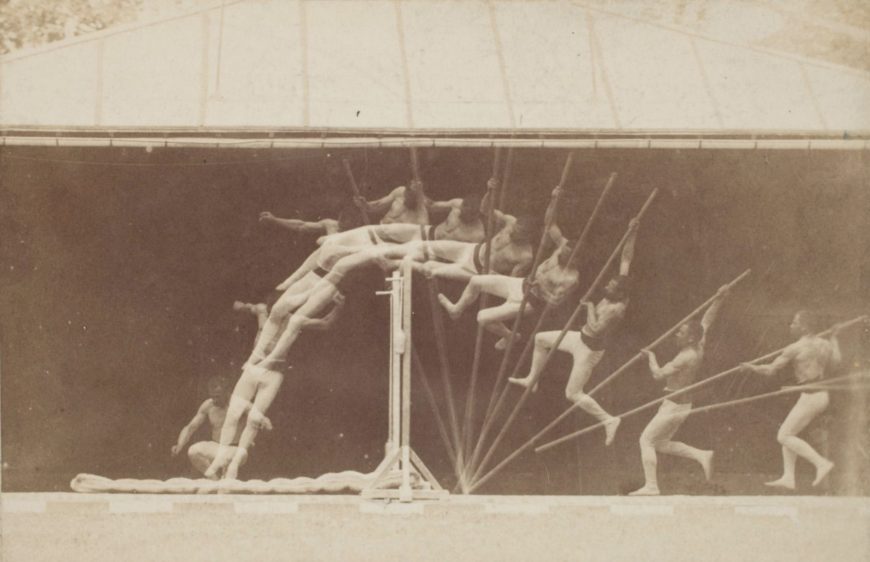

In 1882, Marey invented chronophotography, the capturing of multiple separate and sequential movements of an object. Marey took two approaches to chronophotography, one involving multiple pictures of the same naturalistic and recognizable subject superimposed and overlapping on the same plate, exemplified by Chronophotographic Study of Man Pole Vaulting.

Étienne-Jules Marey, Chronophotographic Study of Man Pole Vaulting, c. 1890, albumen silver print, 6.9 × 10.6 cm (Eastman Museum)

To make Chronophotographic Study of Man Pole Vaulting and Joinville Soldier Walking, Marey used a camera with a single, light-sensitive plate, equipped with a motor-driven rotary-disc shutter that turned and rapidly opened and closed the shutter, controlling the flow of light, intermittently. The camera recorded the appearance, in a fractions of a second, of an object sequentially moving across a picture plane.

Rotary disk shutter (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Marey’s other approach to chronophotography, “geometric chronophotography,” still included multiple overlapping exposures of a single subject, taken sequentially, as it moved across the frame. But in “geometric chronophotographs” like Joinville Soldier Walking, the subject appears as an abstract pattern of lines and dots. To achieve this effect, Marey photographed a subject wearing a black “motion suit” with white stripes down the sleeves and legs, and spots on the heads and active joints of the body, as we see in Marey’s photograph of assistant Georges Demenÿ. The suited subject walked or ran in front of a black backdrop as the camera recorded sequential movements. Instead of seeing whole bodies frozen in sequential superimposed motions, geometric chronophotographs revealed abstracted expressions of movement as undulating stripes of slanted lines, dots, and wavy bands as we see in Joinville Soldier Walking.

Marey and Demenÿ made Joinville Soldier Walking at a military school in Joinville, France, to analyze the fit young men’s walking and running movements to determine their efficiency, and adjust training programs, as needed. With the support of the French Ministry of War, they hoped to help gather data at Joinville to evaluate the effectiveness of military training. [2] However, Marey’s intended purpose for the photographs—to rigorously and scientifically study the biomechanics of human movement by analyzing the pictures like graphs—eluded him. Frustrated, Marey commented that the photographs failed as scientific inscriptions because they only offered “an approximate idea of the sequence of the various phases of movement, because its record is one of intermittent indications, instead of the continuous record of a curve.” [3]

Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912, oil on canvas, 151.8 x 93.3 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Marey’s influence on fine art: capturing motion, the Unseen

Even though the chronophotographs were not as scientifically valuable as he would have liked, Marey’s experiments unintentionally inspired not only the creation of cinema, but a generation of fine artists. [4] His work influenced the motion-implying, abstraction-embracing Orphic Cubists Robert and Sonia Delaunay, and František Kupka, as well as Suprematists Kazimir Malevich and Natalia Goncharova, who evoked the fourth dimension (time) in their work. [5]

In addition, as the Italian Futurists sought to visually arrest the dynamism and energy of the industrial/machine age, they looked to Marey’s repeated forms, abstracted shapes, and linear dynamism as a means of implying motion on a still surface (see the artwork of Luigi Russolo, Umberto Boccioni, or Giacomo Balla’s Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash from 1912).

Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase revealed a dynamic, brown-toned Cubo-Futurist rendition of the successive steps of abstracted movement of a body fractured into successive planes that simultaneously appear as it descends several steps of stairs. [6] Limbs are fractured, abstracted, and repeated in Duchamp’s painting, just as the slanted bands of wavy lines likewise are fractured, reduced to a vocabulary of geometries, and reiterated in Marey’s Joinville Soldier Walking.

Chronophotographs such as Joinville Soldier Walking were, to Marey, only somewhat useful for the scientific analysis of biomechanics. Despite their limitations, they freed the imaginations of many artists and their legacy arguably was far greater.