Charlemagne, King of the Franks and later Holy Roman Emperor, instigated a cultural revival known as the Carolingian Renaissance. This revival used Constantine’s Christian empire as its model, which flourished between 306 and 337. Constantine was the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity and left behind an impressive legacy of military strength and artistic patronage.

Charlemagne saw himself as the new Constantine and instigated this revival by writing his Admonitio generalis (789) and Epistola de litteris colendis (c.794–797). In the Admonitio generalis, Charlemagne legislates church reform, which he believes will make his subjects more moral and in the Epistola de litteris colendis, a letter to Abbot Baugulf of Fulda, he outlines his intentions for cultural reform. Most importantly, he invited the greatest scholars from all over Europe to come to court and give advice for his renewal of politics, church, art and literature.

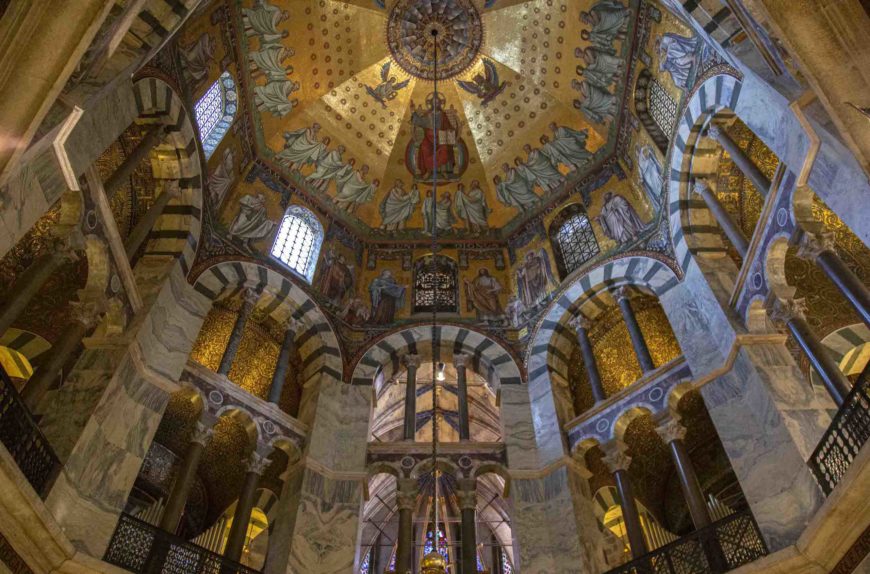

Odo of Metz, Palatine Chapel Interior, Aachen, 805 (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Carolingian art survives in manuscripts, sculpture, architecture and other religious artifacts produced during the period 780–900. These artists worked exclusively for the emperor, members of his court, and the bishops and abbots associated with the court. Geographically, the revival extended through present-day France, Switzerland, Germany and Austria.

Charlemagne commissioned the architect Odo of Metz to construct a palace and chapel in Aachen, Germany. The chapel was consecrated in 805 and is known as the Palatine Chapel. This space served as the seat of Charlemagne’s power and still houses his throne today.

The Palatine Chapel is octagonal with a dome, recalling the shape of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy (completed in 548), but was built with barrel and groin vaults, which are distinctively late Roman methods of construction. The chapel is perhaps the best surviving example of Carolingian architecture and probably influenced the design of later European palace chapels.

Charlemagne had his own scriptorium, or center for copying and illuminating manuscripts, at Aachen. Under the direction of Alcuin of York, this scriptorium produced a new script known as Carolingian miniscule. Prior to this development, writing styles or scripts in Europe were localized and difficult to read. A book written in one part of Europe could not be easily read in another, even when the scribe and reader were both fluent in Latin. Knowledge of Carolingian miniscule spread from Aachen was universally adopted, allowing for clearer written communication within Charlemagne’s empire. Carolingian miniscule was the most widely used script in Europe for about 400 years.

Figurative art from this period is easy to recognize. Unlike the flat, two-dimensional work of Early Christian and Early Byzantine artists, Carolingian artists sought to restore the third dimension. They used classical drawings as their models and tried to create more convincing illusions of space.

St. Mark from the Godescalc Gospel Lectionary, folio 1v., c. 781–83 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

This development is evident in tracing author portraits in illuminated manuscripts. The Godescalc Gospel Lectionary, commissioned by Charlemagne and his wife Hildegard, was made circa 781–83 during his reign as King of the Franks and before the beginning of the Carolingian Renaissance. In the portrait of St. Mark, the artist employs typical Early Byzantine artistic conventions. The face is heavily modeled in brown, the drapery folds fall in stylized patterns and there is little or no shading. The seated position of the evangelist would be difficult to reproduce in real life, as there are spatial inconsistencies. The left leg is shown in profile and the other leg is show straight on. This author portrait is typical of its time.

The Ebbo Gospels were made c. 816–35 in the Benedictine Abbey of Hautvillers for Ebbo, Archbishop of Rheims. The author portrait of St. Mark is characteristic of Carolingian art and the Carolingian Renaissance. The artist used distinctive frenzied lines to create the illusion of the evangelist’s body shape and position. The footstool sits at an awkward unrealistic angle, but there are numerous attempts by the artist to show the body as a three-dimensional object in space. The right leg is tucked under the chair and the artist tries to show his viewer, through the use of curved lines and shading, that the leg has form. There is shading and consistency of perspective. The evangelist sitting on the chair strikes a believable pose.

St. Mark from the Ebbo Gospels, folio 60v., c. 816–35 (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Charlemagne, like Constantine before him, left behind an almost mythic legacy. The Carolingian Renaissance marked the last great effort to revive classical culture before the Late Middle Ages. Charlemagne’s empire was led by his successors until the late ninth century. In early tenth century, the Ottonians rose to power and espoused different artistic ideals.

Additional resources:

Carolingian Art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

A Carolingian Masterpiece: the Moutier-Grandval Bible from the British Library