Approximate boundaries of the Byzantine Empire at its greatest extent in the mid-6th century (underlying map © Google)

To speak of “Byzantine Art” is a bit problematic, since the Byzantine empire and its art spanned more than a millennium and penetrated geographic regions far from its capital in Constantinople. Thus, Byzantine art includes work created from the fourth century to the fifteenth century and encompassing parts of the Italian peninsula, the eastern edge of the Slavic world, the Middle East, and North Africa. So what is Byzantine art, and what do we mean when we use this term?

Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, 532–37 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

It’s helpful to know that Byzantine art is generally divided up into three distinct periods:

| Early Byzantine | c. 330–843 |

| Middle Byzantine | c. 843–1204 |

| Late Byzantine | c. 1261–1453 |

Early Byzantine (c. 330–843)

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George, sixth or early seventh century, encaustic on wood, 2′ 3″ x 1′ 7 3/8″ (St. Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt)

The Emperor Constantine adopted Christianity and in 330 moved his capital from Rome to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), at the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire. Christianity flourished and gradually supplanted the Greco-Roman gods that had once defined Roman religion and culture. This religious shift dramatically affected the art that was created across the empire.

The earliest Christian churches were built during this period, including the famed Hagia Sophia (above), which was built in the sixth century under Emperor Justinian. Decorations for the interior of churches, including icons and mosaics, were also made during this period. Icons, such as the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (left), served as tools for the faithful to access the spiritual world—they served as spiritual gateways.

Similarly, mosaics, such as those within the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, sought to evoke the heavenly realm. In this work, ethereal figures seem to float against a gold background that is representative of no identifiable earthly space. By placing these figures in a spiritual world, the mosaics gave worshipers some access to that world as well. At the same time, there are real-world political messages affirming the power of the rulers in these mosaics. In this sense, art of the Byzantine Empire continued some of the traditions of Roman art.

Justinian mosaic, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Generally speaking, Byzantine art differs from the art of the Romans in that it is interested in depicting that which we cannot see—the intangible world of Heaven and the spiritual. Thus, the Greco-Roman interest in depth and naturalism is replaced by an interest in flatness and mystery.

Middle Byzantine (c. 843–1204)

The Middle Byzantine period followed a period of crisis for the arts called the Iconoclastic Controversy, when the use of religious images was hotly contested. Iconoclasts (those who worried that the use of images was idolatrous), destroyed images, leaving few surviving images from the Early Byzantine period. Fortunately for art history, those in favor of images won the fight and hundreds of years of Byzantine artistic production followed.

The stylistic and thematic interests of the Early Byzantine period continued during the Middle Byzantine period, with a focus on building churches and decorating their interiors. There were some significant changes in the empire, however, that brought about some change in the arts. First, the influence of the empire spread into the Slavic world with the Russian adoption of Orthodox Christianity in the tenth century. Byzantine art was therefore given new life in the Slavic lands.

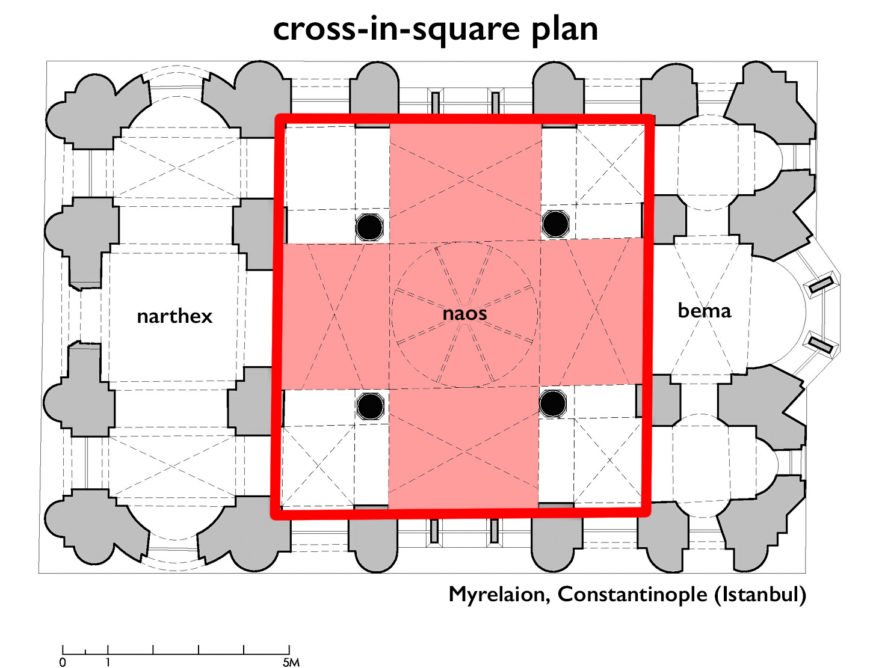

Cross-in-square plan, the Myrelaion church (Bodrum Mosque), c. 920, Constantinople (Istanbul) (adapted from plan © Vasileios Marinis)

Architecture in the Middle Byzantine period overwhelmingly moved toward the centralized cross-in-square plan for which Byzantine architecture is best known.

Central dome and squiches, 11th century, mosaic, narthex, katholikon, Hosios Loukas, Boeotia (photo: Evan Freeman, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Hosios Loukas, Greece, early 11th century (photo: Jonathan Khoo, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

These churches were usually on a much smaller-scale than the massive Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, but, like Hagia Sophia, the roofline of these churches was always defined by a dome or domes. This period also saw increased ornamentation on church exteriors. A particularly good example of this is the tenth-century Hosios Loukas Monastery in Greece.

Harbaville Triptych, ivory, traces of polychromy, 28.2 x 24.2 cm (Louvre)

Lower register (detail), Harbaville Triptych, ivory, traces of polychromy, 28.2 x 24.2 cm (Louvre; photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen)

This was also a period of increased stability and wealth. As such, wealthy patrons commissioned private luxury items, including carved ivories, such as the celebrated Harbaville Tryptich, which was used as a private devotional object. Like the sixth-century icon discussed above (Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George), it helped the viewer gain access to the heavenly realm. Interestingly, the heritage of the Greco-Roman world can be seen here, in the awareness of mass and space. See for example the subtle breaking of the straight fall of drapery by the right knee that projects forward in the two figures in the bottom register of the Harbaville Triptych (left). This interest in representing the body with some naturalism is reflective of a revived interest in the classical past during this period. So, as much as it is tempting to describe all Byzantine art as “ethereal” or “flattened,” it is more accurate to say that Byzantine art is diverse. There were many political and religious interests as well as distinct cultural forces that shaped the art of different periods and regions within the Byzantine Empire.

Late Byzantine (c. 1261–1453)

Between 1204 and 1261, the Byzantine Empire suffered another crisis: the Latin Occupation. Crusaders from Western Europe invaded and captured Constantinople in 1204, temporarily toppling the empire in an attempt to bring the eastern empire back into the fold of western Christendom. (By this point Christianity had divided into two distinct camps: eastern [Orthodox] Christianity in the Byzantine Empire and western [Latin] Christianity in the European west.)

Anastasis (Harrowing of Hell), c. 1310–20, fresco, Church of the Holy Savior of Chora/Kariye Museum, Istanbul (photo: Till.niermann, CC BY-SA 3.0)

By 1261 the Byzantine Empire was free of its western occupiers and stood as an independent empire once again, albeit markedly weakened. The breadth of the empire had shrunk, and so had its power. Nevertheless Byzantium survived until the Ottomans took Constantinople in 1453. In spite of this period of diminished wealth and stability, the arts continued to flourish in the Late Byzantine period, much as it had before.

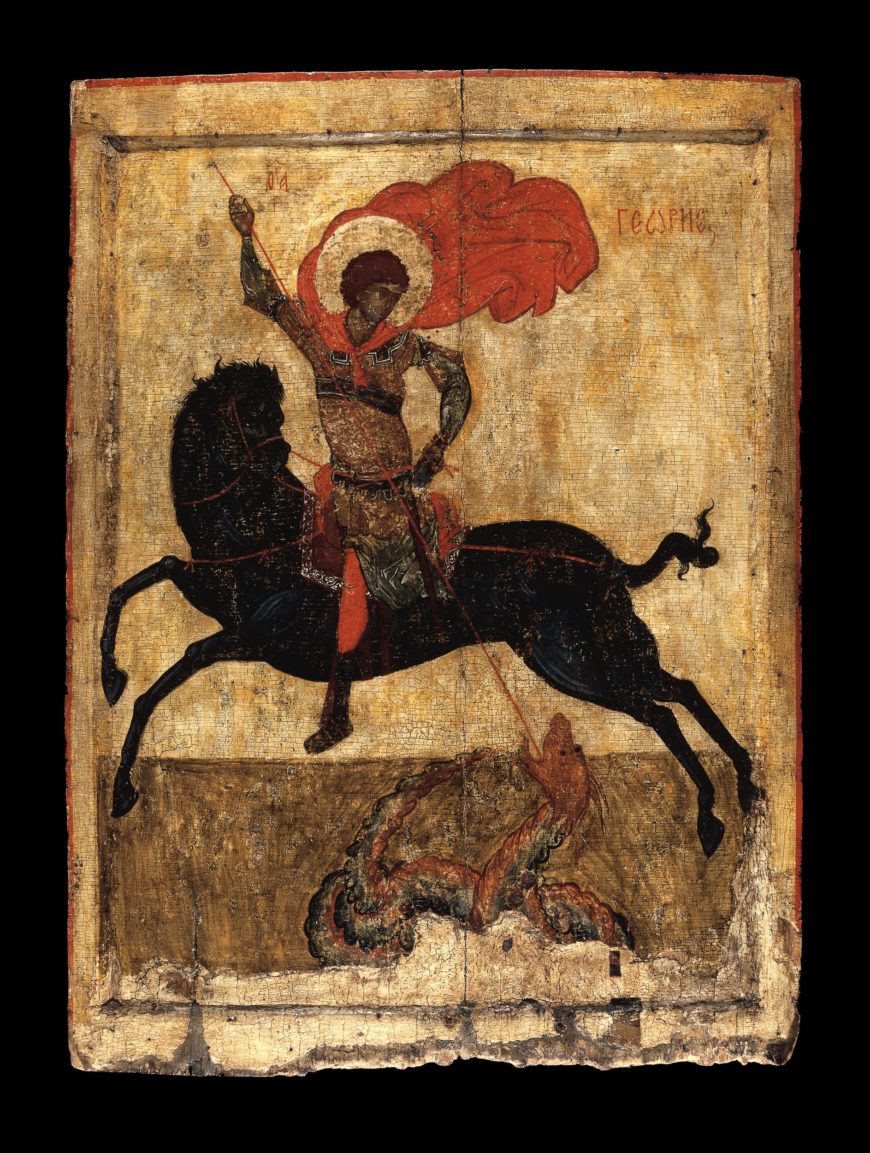

Icon of St. George (‘The Black George’), c. 1400–50, tempera on panel, 77.4 x 57 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Although Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453—bringing about the end of the Byzantine Empire—Byzantine art and culture continued to live on in its far-reaching outposts, as well as in Greece, Italy, and the Ottoman Empire, where it had flourished for so long. The Russian Empire, which was first starting to emerge around the time Constantinople fell, carried on as the heir of Byzantium, with churches and icons created in a distinct “Russo-Byzantine” style (left). Similarly, in Italy, when the Renaissance was first emerging, it borrowed heavily from the traditions of Byzantium. Cimabue’s Madonna Enthroned of 1280–90 is one of the earliest examples of the Renaissance interest in space and depth in panel painting. But the painting relies on Byzantine conventions and is altogether indebted to the arts of Byzantium.

So, while we can talk of the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, it is much more difficult to draw geographic or temporal boundaries around the empire, for it spread out to neighboring regions and persisted in artistic traditions long after its own demise.