Krishna Uprooting the Parijata Tree from a Bhagavata Purana manuscript, 1525–50, made in Delhi region or Rajasthan, India, opaque watercolor and ink on paper, 7 1/4 × 9 1/2 inches (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, from the Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Museum Associates Purchase, M.72.1.26, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA)

The word “paradise” often describes an idyllic place of unmatched beauty, but it can also refer to a mindset of harmony and bliss. Several world religions share these conceptions of paradise, but the paths for locating it—whether in a physical environment, a metaphysical realm like heaven, or a state of transcendence—have varied greatly. The image above shows the blue-skinned Hindu deity Krishna (an incarnation of Vishnu, “the preserver”) transplanting the sacred parijata tree from heaven. He carries the plant to earth along with his wife Satyabhama, who ride together atop an eagle-like mythical being called Garuda. At right, the many-eyed god Indra and his consort witness the event.

A Global Middle Ages

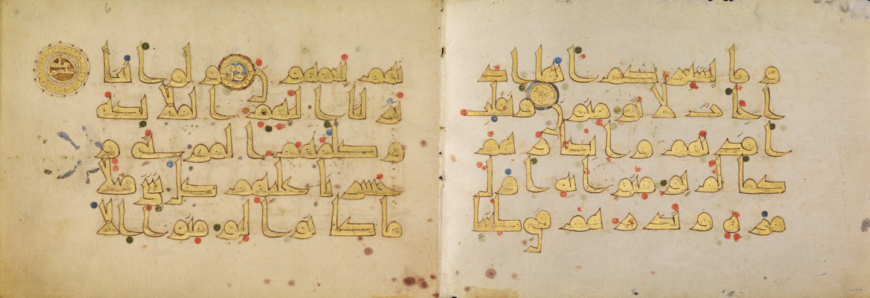

Text Pages from a Qur’an (Surah 6:109-111), ninth century (third century AH), made in North Africa. Pen and ink, gold paint, and tempera colors, 5 11/16 × 8 3/16 in. (each leaf) (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig X 1 (83.MM.118), fols. 5v-6)

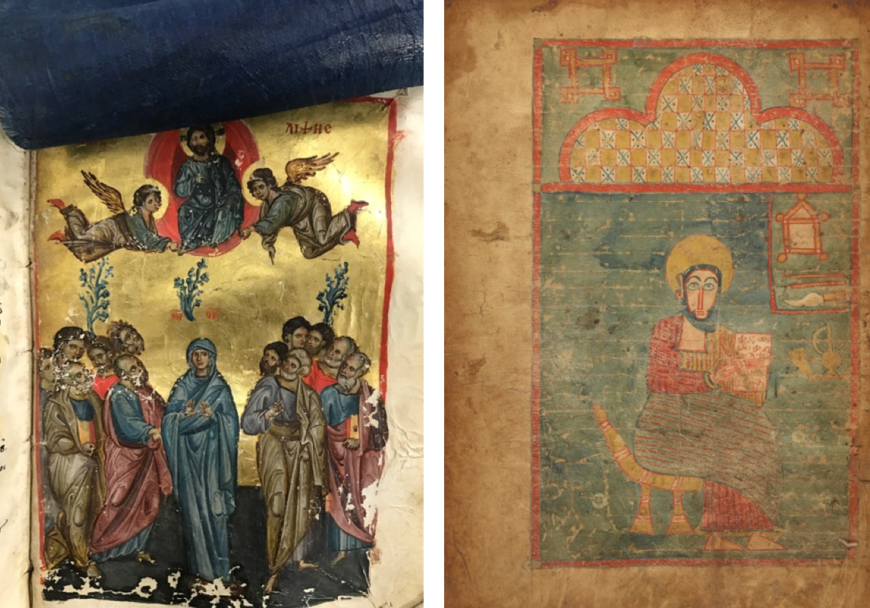

The majority of the manuscripts in the Getty’s collection were produced in Western Europe from the ninth through the sixteenth century, with additional examples from important centers of the Byzantine world (the Eastern Roman Empire), Armenia, Ethiopia, and elsewhere. Exhibitions allow us to expand the traditional narratives about a European Middle Ages to consider a global Middle Ages of trasnational connections. By doing so, our holdings of a ninth-century Qur’an from Tunisia (above), a silk veil in a thirteenth-century Byzantine Gospel book, and a page from a fifteenth-century Gospel book from Ethiopia (both below) find new relationships alongside leaves from Buddhist manuscripts on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art—all of which include areas painted or dyed with the blue pigment indigo, which was largely sourced in India at the time.

The Ascension in a Gospel book, with silk veil (top) used to protect the sacred image, early and late 13th century, made in Nicea or Nicomedia, Turkey. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment, 8 1/8 × 5 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig II 5 (83.MB.69), fol. 188. Saint John from a Gospel book, late fourteenth–early fifteenth century, made in Ethiopia. Tempera colors on parchment, 13 1/4 × 9 3/16 inches (The J. Paul Getty Museum, gift of Sam Fogg, Ms. 89 (2005.3), verso).

Empires in the Indian subcontinent, the Hindu Kush, and the Tibetan or Himalayan Plateau shared intertwined histories with principalities to the west, from the Greeks and Romans to the Persianate, Christian, and Islamic kingdoms of Central Asia or East Africa. Similarly, peoples throughout Europe and the Mediterranean had contact with and developed imagined ideas about the land of India—its peoples, religions, and natural wonders—since ancient times. Art from Gandhara (present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan), for example, combined elements from Greece, Rome, Persia, and local traditions, demonstrating the long history of contact at this crossroads of civilizations.

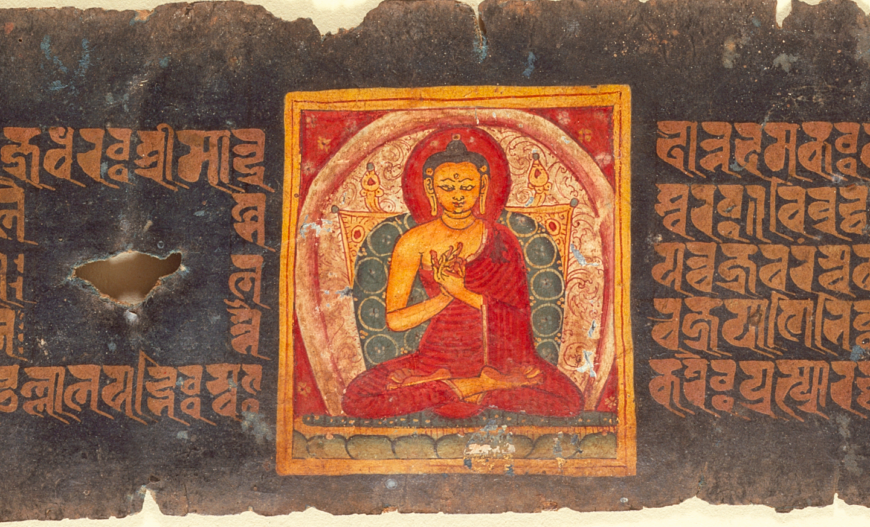

Buddha Shakyamuni (detail) from a Paramartha Namasangiti manuscript, about 1200, made in Nepal. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 3 × 10 7/8 in. (full sheet) (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Peter Smoot in memory of Herbert R. Cole, M.83.7.1)

Head of a Bodhisattva, third century, made in Gandhara. Schist, 9 in. high. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Gift of Dr. Sidney and Idelle Port, 83.AJ.390)

In the exhibition, a beautifully carved Gandharan head of a bodhisattva—an enlightened follower of the Buddha who helps others reach Nirvana (release from cycles of desire and suffering)—greets visitors upon entering the gallery. A mostly complete statue from the Norton Simon Museum gives a sense of the various cultural influences (the bodhisattva Maitreya wears a Greco-Roman style toga), and a relief from LACMA shows Buddha Shakyamuni seated near a Corinthian column, another instance of Roman inspiration.

The Middle Ages (about 500–1500) witnessed increased movement between Europe, Byzantium, the Islamic world, and India. One of the historical figures whose legacy links these cultures is Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.E.), whose military campaigns took him from Macedonia to Northwest India. This range explains some of the transculturation in art from regions like Gandhara. Few contemporary accounts survive about the Macedonian world ruler, but classical and medieval writers in Europe, Central Asia, and India preserved his memory through histories, chronicles, and romances.

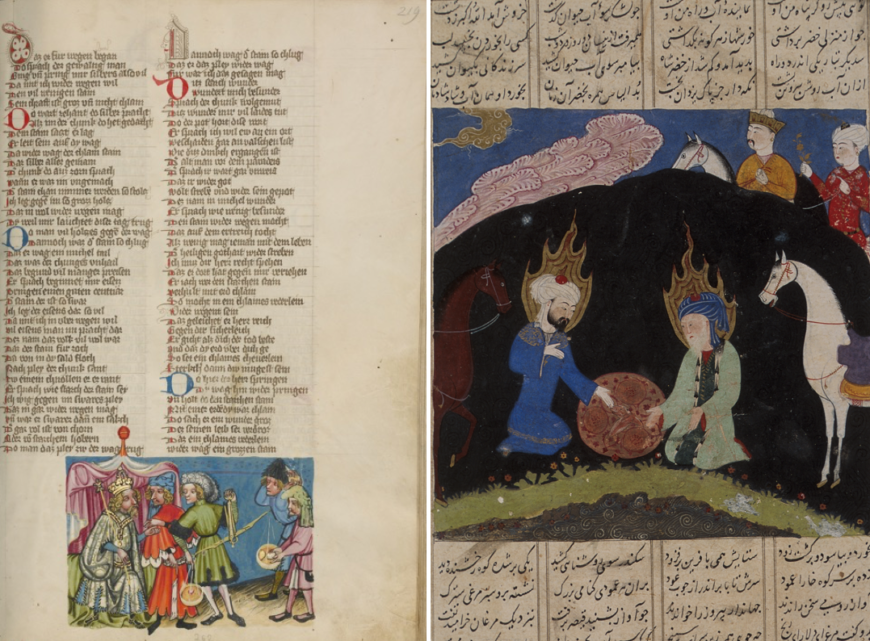

Rudolf von Ems (about 1200–1254) based this German World Chronicle on Roman sources, which cast Alexander as an ideal ruler from “the East.” According to the text, Alexander sought the mythical earthly paradise during his military campaigns across Asia. On one journey, an elderly man presented the ruler with a precious gem said to be from paradise, which weighed more than any other jewel. When the stone was ground into a powder, it became light and worthless. The message to Alexander was that his reign would be great in life but forgotten in death, a paradox given his enduring fame today.

Left: Alexander the Great Has the Stone of Paradise Weighed from Rudolf von Ems’s World Chronicle, about 1400–10, made in Regensburg, Bavaria. Tempera colors, gold, silver paint, and ink on parchment,13 3/16 × 9 1/4 in. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 33, 88.MP.70), fol. 219; right: Iskandar Finds Khizar and Ilyas at the Fountain of Immortality from Nizami’s Khamza, 1485–95, made in Shiraz, Iran. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 8 7/8 x 6 inches (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky, M.73.5.590)

The cross-cultural legacy of Alexander the Great is also present in a fifteenth century Persian text from Iran called the Khamsa of Nizami (1141–1209). Following military campaigns in Eastern Africa, India, and China, the world-ruler Iskandar (Persian for Alexander the Great) began a journey to find the Fountain of Immortality. Nizami wrote that the magical youth-granting waters flowed from the North Pole. The prophets Khizar and Ilyas guide Iskandar through a place called the Land of Gloom or Darkness but they also conceal the stream of the Fountain. The rich traditions for illuminated manuscripts about Alexander/Iskandar connected distant regions of Eurasia from ancient to Early Modern times, especially episodes about his more fantastic exploits or encounters, such as his journeys under the sea or into the sky.

Mapping the Premodern World: A View from Europe

Portolan Chart, 1516, Vesconte Maggiolo, made in Naples. Parchment, 102 x 152 cm. (The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California, HM 427)

A nearly-five-foot-long map designed by cartographer Vesconte Maggiolo (1478–1530) in 1516 provides a point of connection. From India and Central Asia in the East to the Caribbean and the Americas to the West, the map presents an extensive view of the world as understood by a man living in Naples in the early sixteenth century (explore a high-resolution version of the map here).

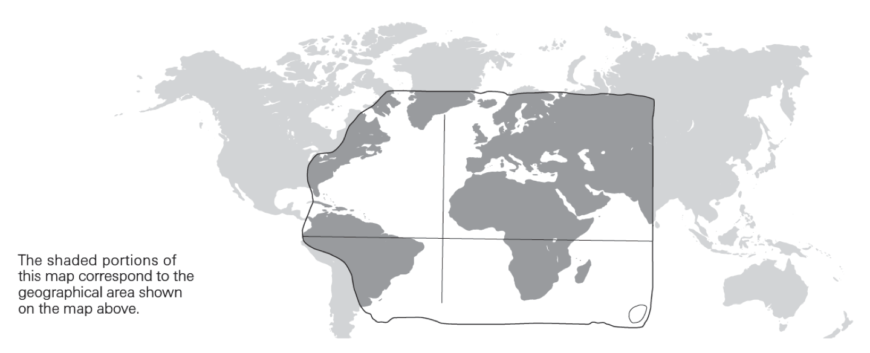

Schematic diagram of the Portolan Chart showing its position on a world map (credit: Jennifer Minasian)

Across Afro-Eurasia, Vesconte Maggiolo depicted tents and enthroned rulers to mark the major kingdoms known to him, including Morocco, France, and Persia. Multicolored islands indicate fabled sites of gem mining, silk production, and the spice trade, all of which derive from a long literary and visual tradition in the Mediterranean. A roundel of the Virgin and Child, situated in the Atlantic Ocean near several ships returning to Europe, suggests the missionary and mercantile agendas of the period.

Details of Portolan Chart showing the Virgin and Child in the Atlantic with ships, and the Kingdom of Prester John and the Garden of Eden (The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California, HM 427)

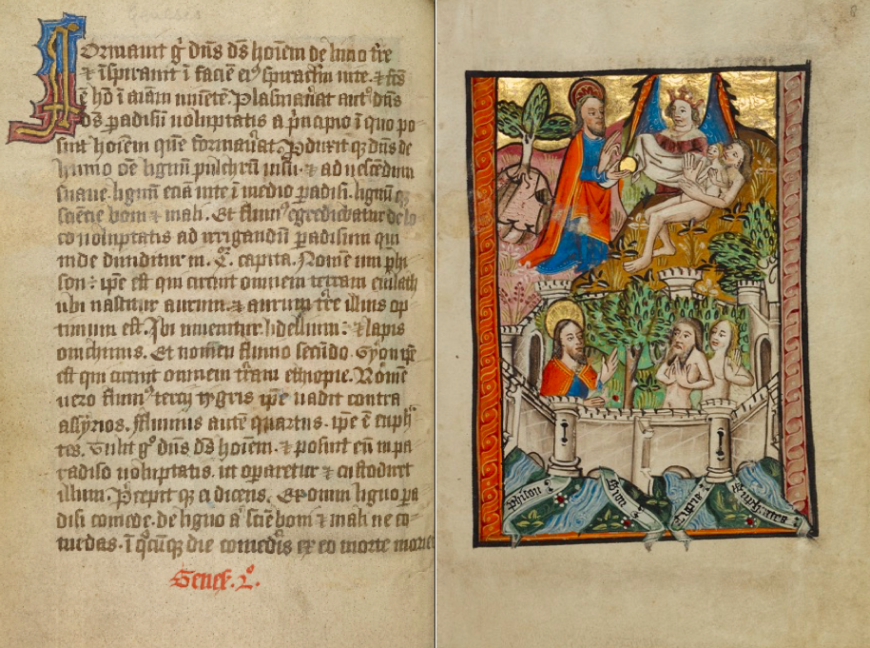

On the map, the earthly paradise known as the Garden of Eden emerges in the kingdom of Prester John, a mythical Christian king shown here in Africa (in the vicinity of Ethiopia) but who was also associated with India or lands farther east. The biblical book of Genesis describes the paradisiacal garden at the source of four rivers: the Pison (possibly in Syria), the Gihon (said to be in Ethiopia), and the Tigris and Euphrates (in ancient Mesopotamia, primarily in present-day Iraq). The artist of a devotional manuscript made in East Anglia, England labeled the rivers and showed them surging forth from a walled orchard where God placed Adam and Eve.

The Garden of Eden in an illustrated Vita Christi with devotional supplements, about 1490, made in East Anglia, England (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 101, 2008.3), fols. 7v–8.

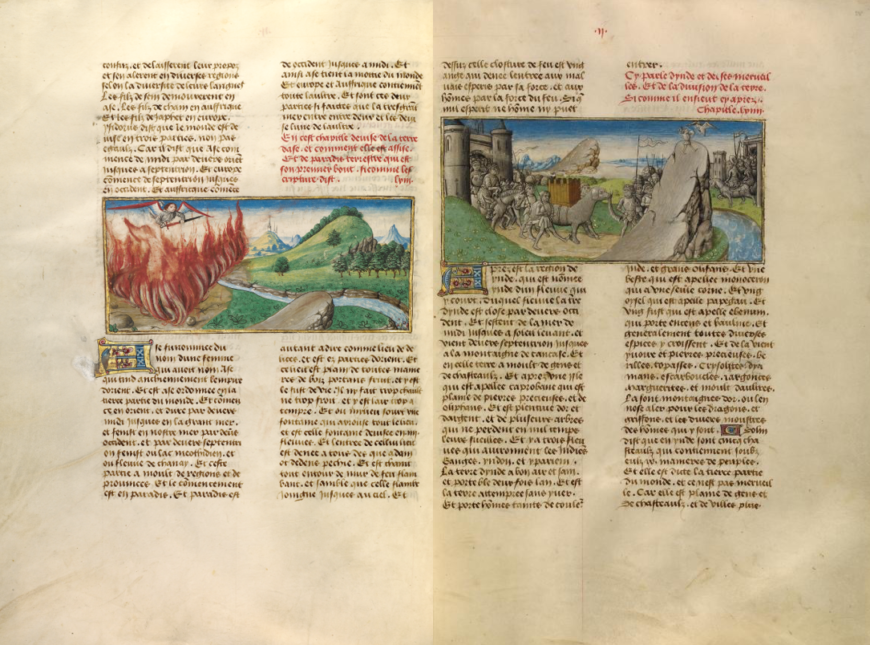

The Dominican writer Vincent of Beauvais (1184–1264) wrote a comprehensive world history that began with the biblical creation story and extended to the year 1254. He derived his knowledge of the East from a range of sources, including the Roman author Solonius (third century) and the Franciscan missionary John of Plano Carpini (about 1185–1252). Accordingly, Vincent of Beauvais locates the Garden of Eden not in Ethiopia but beyond the land of India and the Island of Taprobane (Sri Lanka). In other words, paradise was a place that was virtually inaccessible in the spatial imagination of sedentary writers, readers, and viewers in Europe.

The Angel of Paradise with a Sword and The Land of India in Vincent of Beauvais’s Mirror of History, Ghent, about 1475. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment, 17 1/4 × 12 inches (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XII 5, 83.MP.148), vol. 1, fols. 54v–55.

The Angel of Paradise with a Sword (detail) in Vincent of Beauvais’s Mirror of History, about 1475, made in Ghent. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment, 17 1/4 × 12 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XII 5 (83.MP.148), vol. 1, fol. 54v.

Based on the descriptions in the text, the illuminator rendered an elephant, a griffin, and blue-skinned people wearing indigo-dyed clothing. Additionally, the author mentions exports from East Asia that include spices and ivory, as well as gems believed to come from the rivers of paradise (the detail shows purple, red, and green jewels within one of the rivulets). The relationship between gems and India is a theme explored in the exhibition through a range of objects produced from the Rhine-Meuse region in Europe to Jammu and Kashmir in India.

Infinite Gems: The Auspicious Çintemani

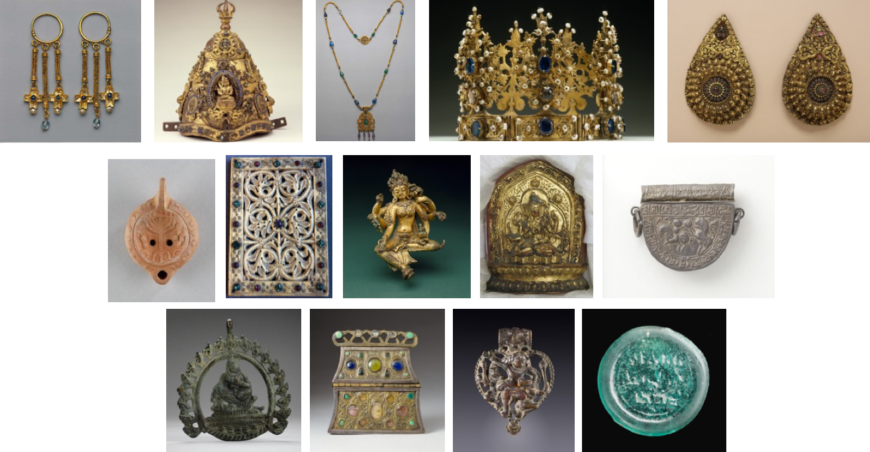

People, manuscripts, and luxury items moved with considerable frequency throughout the premodern world. An ivory plaque (middle row, below, second from left), for example, likely came from the tusk of an African elephant, and once carved, it adorned the cover of a Gospel book from Central Europe. The colored glass pieces were likely meant to simulate rubies and emeralds, precious gemstones often sourced from Central Asia and India, and which symbolically referred to descriptions of Heavenly Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation.

Top row, left to right: Earrings, sixth–seventh century, Byzantine. Ferrell Collection. Ritual Crown, twelfth century, made in Nepal (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of The Ahmanson Foundation, M.81.67). Pendant and Necklace, sixth–seventh century, Byzantine (Ferrell Collection). Articulated Crown, fifteenth century, Bohemia (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of the Judas Collections, M.84.200). Pair of Oversize Earrings for an Image, sixteenth century, made in Tibet (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Helene and Dr. Joseph Pollock, M.89.112.2a-b). Center row, left to right: Lamp, first–fourth century, Roman, made in Asia Minor (The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.AQ.377.273). Ivory Plaque from the binding of a Carolingian lectionary (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IV 1, 83.MD.73). The Buddhist Goddess Vasudhara, twelfth century (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, from the Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection, Museum Associates Purchase, M.79.9.5). Center row, fourth from left: The Buddhist Goddess Ushnishavijaya, eigtheenth century, Tibet or China (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Klejman of New York, M.71.26.7). Amulet, eleventh century, made in Iran.( Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Camilla Chandler Frost, M.2002.1.545.a-b). Bottom row, left to right: Pendant with a Siddha, eighth–ninth century, made in Jammu and Kashmir, India (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Daniel Ostroff, AC1999.239.1). Carolingian Burse-Reliquary, eighth century, made in German (The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.SE.53). Pendant with Narasimha, ninth–tenth century, made in Jammu and Kashmir, India (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by The Smart Family Foundation in memory of Florence Smart Richards, M.91.38). Weight with Arabic Script, ninth–twelfth century, made in Afghanistan (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Neil Kreitman, M.90.175.8)

Other raw materials such as sapphires, turquoise, gold, and silver were especially prized trade goods. Many cultures and religions ascribe magical or healing properties to gems or metals, and these associations often involved ideas about the divine and the afterlife. While some precious goods—such as jewelry, amulets, and reliquaries—were highly portable and therefore had the potential to traverse great distances, other objects—including crowns, oil lamps, and votive statues—could serve local audiences at court, in temples, or in shrines.

Installation views of the exhibition Pathways to Paradise: Medieval India and Europe showing objects in the section “The Power of Gems and Precious Materials”

Buddhist priests in Nepal, for example, wore crowns shaped to recall the division of the universe into earth, atmosphere, and heaven, a cosmological theme complemented by gem settings. A small gilt copper votive sculpture of the Buddhist goddess Vasudhara, bejeweled with semiprecious stones, holds grain, a waterspout, a gem, and a sacred manuscript, all symbols of paradise and prosperity.

Stories from the life of the Buddha reached European audiences through a lengthy process of translation from Sanskrit to Arabic, Georgian, Greek, and eventually Latin and German. Vignettes from the life of the Indian “enlightened one” became part of the hagiography of Christian Saints Josaphat and his spiritual mentor, Barlaam (The name Josaphat derives from the Sanskrit word bodhisattva). The author Rudolf von Ems (c. 1200–1254) wrote that an Indian prince called Josaphat meditated beneath a tree after witnessing illness, old age, and death for the first time, having lived his entire life until that point in a palace. In a sacred grove, Josaphat met the Christian missionary and merchant Barlaam, who offered Josaphat a precious gem (known as the çintemani in Sanskrit or the triratna in Pali).

Josaphat Speaking to the Merchant Barlaam about the Precious Gem in Rudolf von Ems’s Barlaam and Josaphat, 1469, follower of Hans Schilling, made in Hagenau, Alsace, ink, colored washes, and tempera colors on paper, 11 1/4 × 8 in. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 9, 83.MR.179), fol. 43v. Buddha Shakyamuni from an Ashtasarika Prajnaparamita manuscript, fifteenth century, made in Central Tibet (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Pratapaditya Pal, M.82.60)

In a thirteenth-century Tibetan Ashtasarika Prajnaparamita (The Perfection of Wisdom) manuscript, the çintemani design of three dots can be seen in the background of all three pages, as well as on the cloth that extends from the Buddha’s throne (at top). The same pattern can be seen on the thirteenth-century Nepalese Paramartha Namasangiti manuscript shown above. The concept of a wish-granting or protective jewel originated in Hindu and Buddhist sacred texts, but eventually, the motif became a favorite pattern on luxury textiles throughout the Persian Empire, the Islamic world, East Asia, and Europe. As medievalist Jaroslav Fulda has demonstrated, representations in sculpture can be found on the Sasanian tombs at Naqsh-e Rustam, northwest of Persepolis, Iran, and the textile pattern was represented on garments of holy figures as early as the ninth century in the Book of Kells.

I have also found pictorial depictions of the design in Buddhist paintings from Dunhuang to Tibet, Bihar, and elsewhere. The borders around the Prajnaparamita scenes are closely related to cotton and silk textiles from India and the Islamic world, specifically in Persia, suggesting that the çintemani pattern was transmitted by way of the sericulture trade. In the exhibition, a selection of objects highlight these global connections.

Left: Çintemani Lokeshvara, c. sixteenth century, made in Nepal, wood with paint, 52 1/2 inchess high (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Anna Bing Arnold, M.84.93); right:Fragment of a Dress or Furnishing Fabric with Çintemani Design, mid-sixteenth century, made in Bursa or Istanbul (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Edwin Binney the 3rd Collection of Turkish Art, M.85.237.1).

In Nepal, Çintemani Lokesvara is one of the many forms of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, who represents compassion. He grasps in one hand the wish-granting gem—the çintemani—and with the other welcomes all devotees, who would have visited the sculpture in a shrine. A fragment of a dress or furnishing fabric with the çintemani design from Bursa or Istanbul is a focus point in the exhibition—the silver metallic threads on gold and crimson silk satin is truly stunning.

With twenty manuscripts, over twenty coins, fifteen luxury objects, three sculptures, and a textile, the exhibition included numerous potential pathways to paradise. I encourage you to reflect on your own ideas about how to achieve a state of absolute perfection in a busy world.

This essay was first published on the iris (CC BY 4.0)