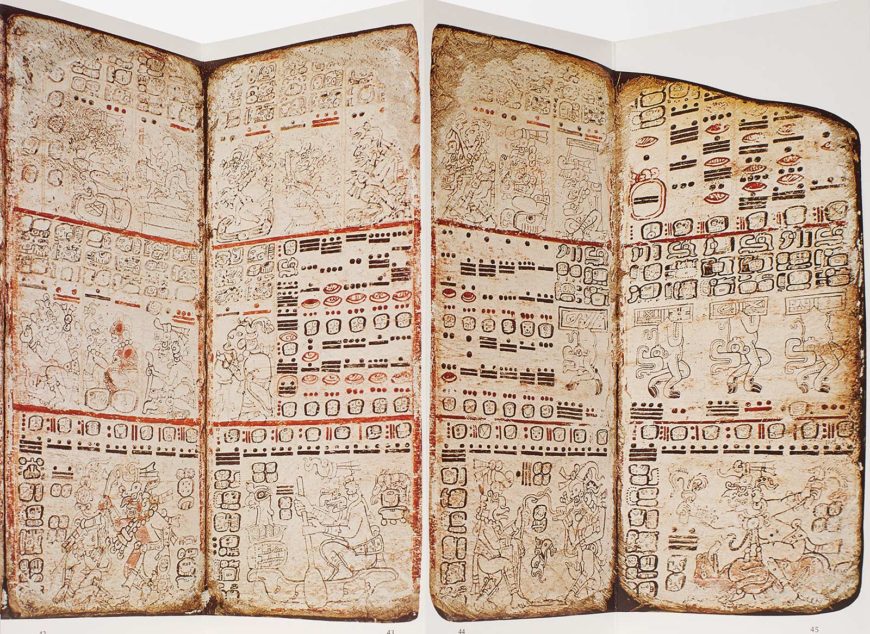

Facsimile of the Dresden Codex (detail), 13th or 14th century, made in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico (Dresden, Germany, Saxon State Library, Mscr.Dresd. R 310. The Getty Research Institute, 2645-271)

Manuscripts and printed books—like today’s museums, archives, and libraries—provide glimpses into how people have perceived the Earth, its many cultures, and everyone’s place in it.

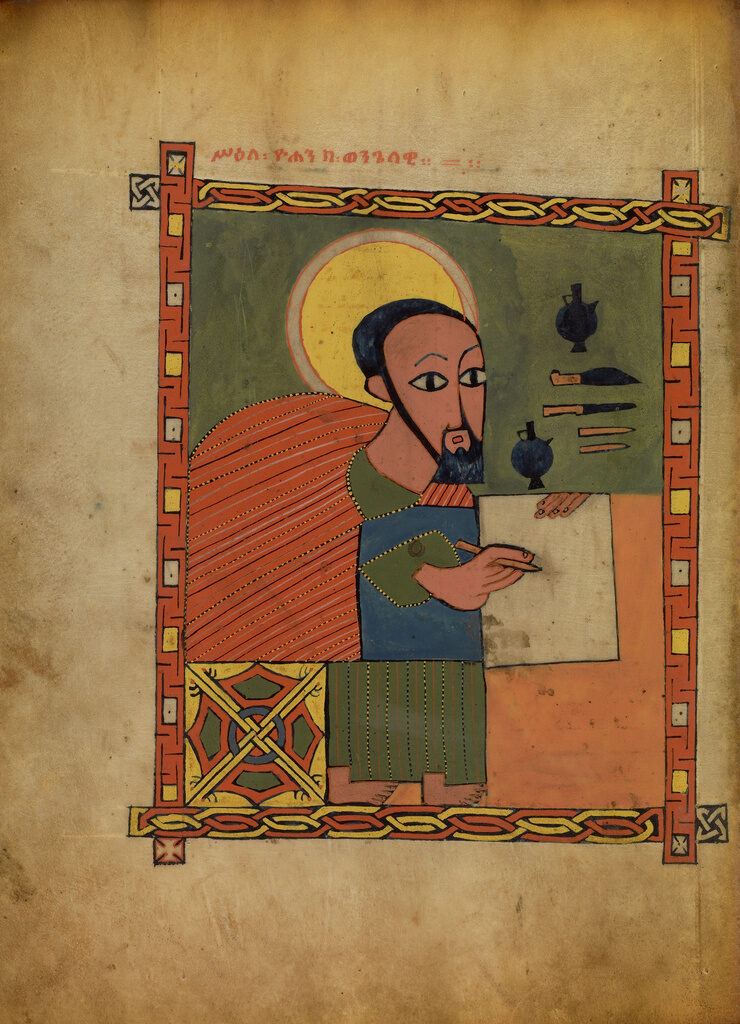

Gospel book, about 1480–1520, made in Gunda Gunde Monastery, Ethiopia (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 105, 2010.17)

The production of books is a collaborative undertaking. In the premodern period, this process could involve the makers of writing surfaces, binding supports, scribes, procurers and creators of pigment, merchants, artists, patrons, and eventually the readers, viewers, or listeners. Toward a Global Middle Ages includes essays by twenty-six authors who are specialists of the art of the book.

Books produced during a global Middle Ages reveal a vast variety of structures and styles. Pages from a Prajnaparamita (The Perfection of Wisdom) manuscript (detail), 1025, made in Bihar, India (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.86.185a-d)

Whose Middle Ages?

What do we mean by a global Middle Ages (or medieval period)? Writing about the Middle Ages has traditionally centered on the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities in Europe, Western Asia, and the greater Mediterranean between the years 500 and 1500. The term “Middle Ages” was used in the nineteenth century to describe a medium aevum, a middle age between the Roman Empire and the Renaissance.

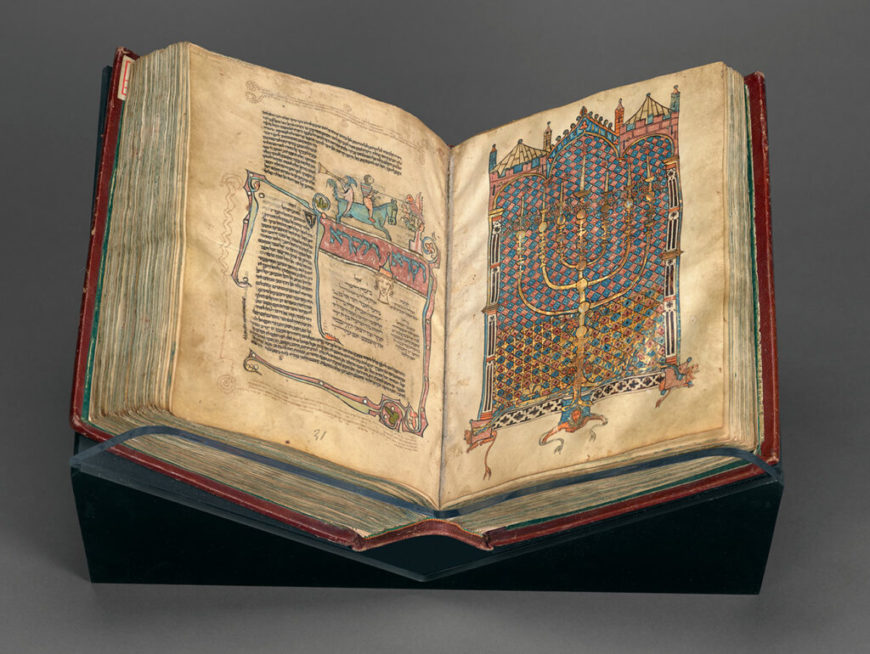

The Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France and/or Germany (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, 2018.43)

For decades, scholars have challenged this Eurocentric view of the past, turning attention to a global Middle Ages that includes Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Austronesia. Some of these scholars seek to uncover networks, pathways, routes, or links between people and places. In doing so, an aim has been to reveal the lives of those who have been silenced by history or tradition: women, enslaved individuals, Indigenous peoples, queer or disabled groups. Others take a comparative approach, examining similar phenomena in different places at the same time or over time. Toward a Global Middle Ages expands upon these perspectives.

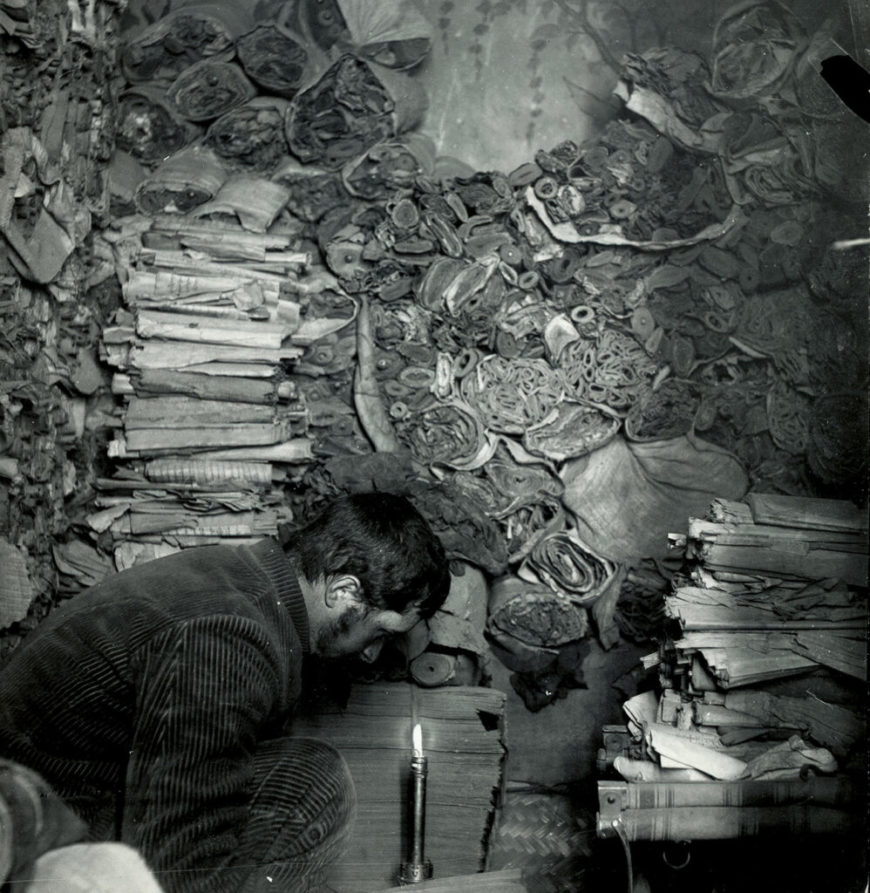

Mogao Caves 16-17 (Library Cave), Dunhuang, Gansu Province, China, 862; sealed around 1000 (photo: Dunhuang Academy)

There are also discussions about the meaning of “global” at a local level, and whether it is possible to speak of early globalities prior to the sustained transatlantic contacts between Europe, the Americas, and Africa in the late fifteenth century (it should be acknowledged that the latter view still largely centers on Europe—as indicated below and in the volume, peoples of northeastern China and Siberia had contacts with First Nation peoples, including those who inhabited the Aleutian Islands).

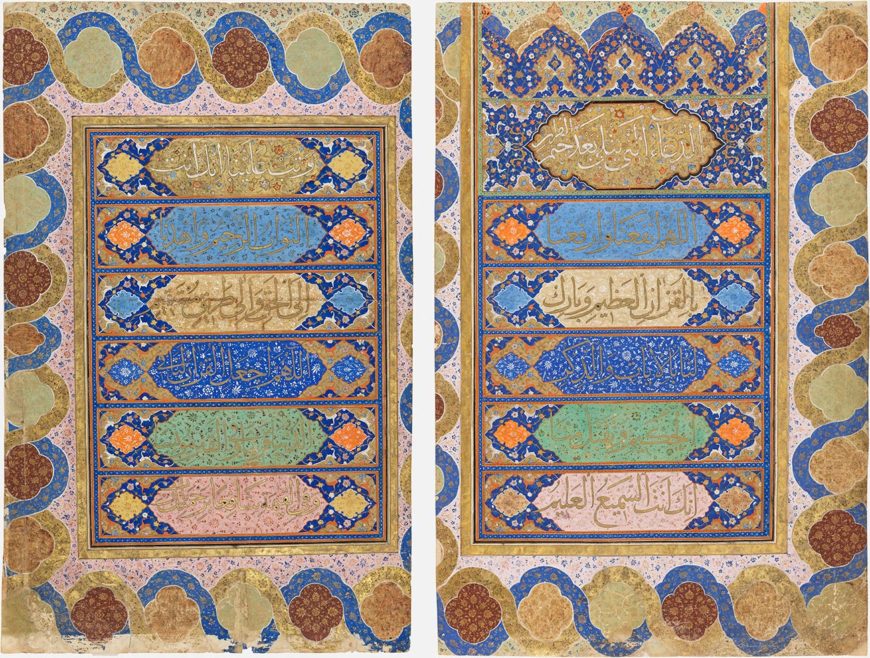

Folios from a Qur’an, Shiraz, Iran, 1550–75 (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2010.54.1)

Some scholars select a hemispheric focus—referring to a hemispheric Middle Ages—that concentrates on Africa, Europe, and Asia on the one hand, and the Americas on the other. With this approach, we can still find connections through comparisons if we look to astronomy or astrology, for example, as I discuss in Toward a Global Middle Ages and have outlined briefly before; we might also consider global climate change (evidenced through ice cores and testimony from manuscripts or oral traditions) and the spread of diseases or the relationship between botany and linguistic development of words for popular trade goods, such as sweet potato or tea. Whichever methodology seems most applicable to the scope of a given study, one recommendation is to continually resist Eurocentrism and to cross boundaries—of periodization, discipline or specialization, historical or present-day geography, language (of documents and of academic training), and so forth.

It takes time to redirect the writing of history. The authors of this book therefore describe what we do as working toward a global Middle Ages.

Paper, Parchment, and Palm Leaves

Books were key modes of cultural expression and exchange throughout the Middle Ages. Manuscript means “handwritten,” from the Latin words manus (“hand”) and scriptus (“written”). Lavish examples were often embellished with metallic leaf or paint that shimmered in the light, which gives us the term “illuminated.” Print technology allowed images and texts to be replicated, and some global traditions combined manuscript and print.

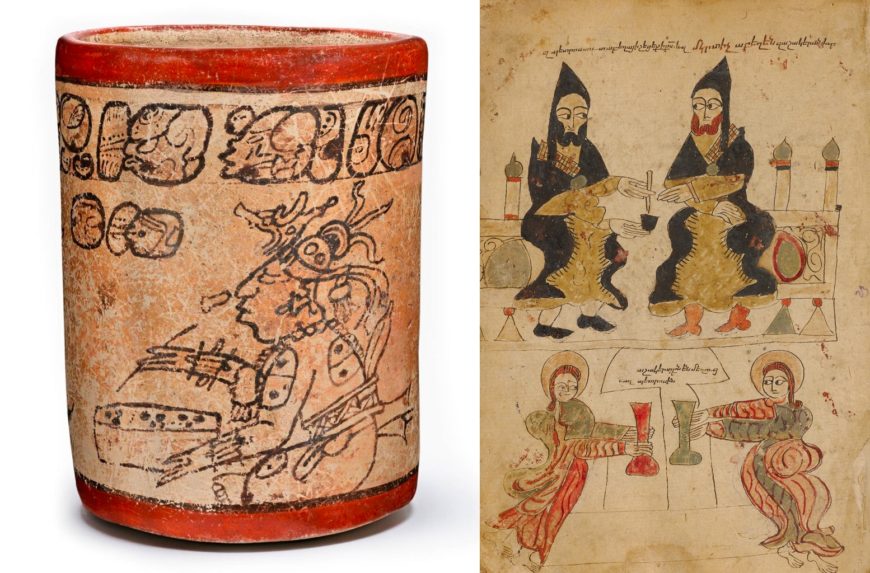

Two images on different supports depicting scribes at work, illustrating the collaborative undertaking of book-making. Left: Codex-Style Cylinder Vessel with Scribes, 650–800, Guatemala or Mexico, Northern Petén or Southern Campeche, Maya, ceramic (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2010.115.562); right: Gospel book, 1386, made in Lake Van, historic Armenian kingdom, black ink and watercolor on paper, 9 7/16 × 6 1/2 inches (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig II 6 (83.MB.70), fol. 13v.)

Across Afro-Eurasia, the Americas, and Austronesia during the medieval period, bookmakers used a variety of supports and structures, including paper, parchment, and palm leaves. Each of these could be gathered together in various ways: bound as a codex, rolled as a scroll, or folded as an album. In some instances, we have to look at other types of artworks for glimpses of book or writing traditions (as with the Maya, whose long history of codex creation was decimated by the Spanish conquest yet ceramic vessels provide evidence for early manuscript production in Mesoamerica). The examples shown in this post hint at the diversity of book types and formats.

Manuscripts and books operated alongside other forms of literacy and visual storytelling throughout the Middle Ages. These include glyphic and graphic examples—characters or symbols carved or painted onto a surface, such as stone, ceramic, or the body—as well as oral traditions and memory aids. Such varied objects shed light on the many ways in which the book, broadly defined, functioned in multiple contexts in the past, and on the relationship between the visual arts and language, storytelling, and the commemoration of the past.

A World Without a Center

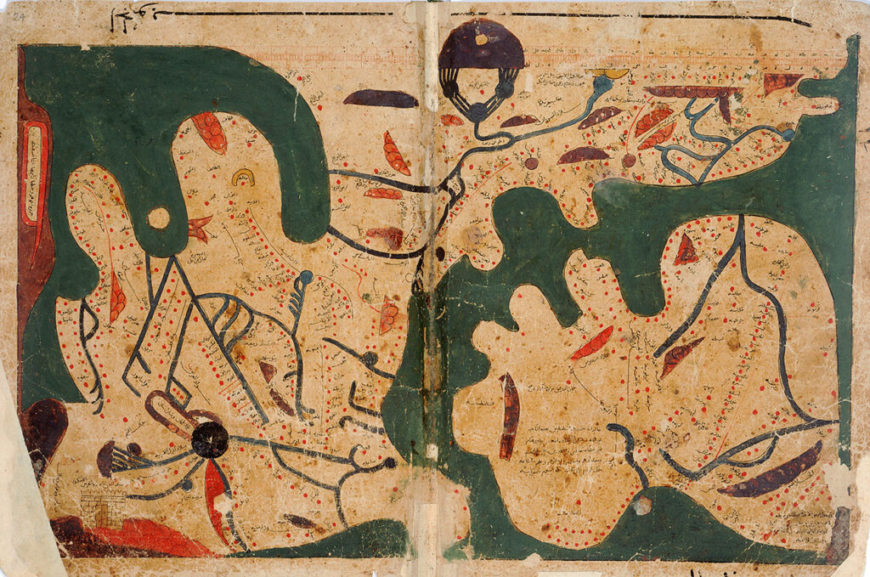

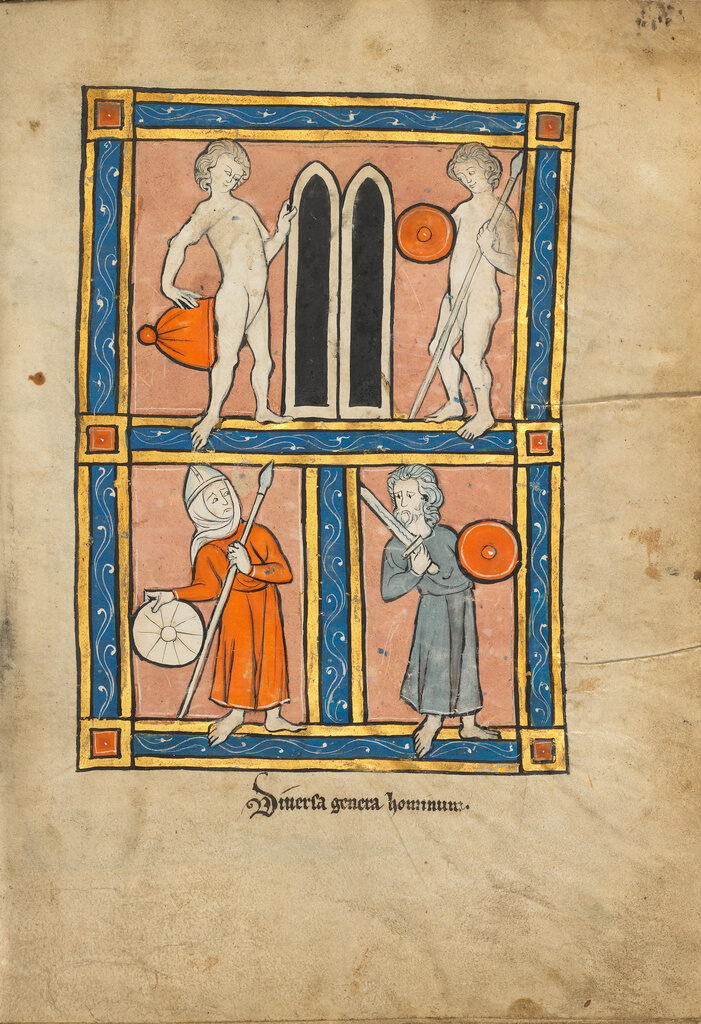

Across the medieval globe, people depicted the world as they knew it, including maps, luxury goods from local and distant lands, legendary peoples, “new worlds,” the “known world,” or even of the universe. World map from the Book of Curiosities of the Sciences and Marvels for the Eyes, Egypt, 1020–50 CE / 410–41 AH (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Arab c.90)

Maps are another focus of the new publication. Like manuscripts, maps present world views, including views of self and others; they also change frequently and are often political.

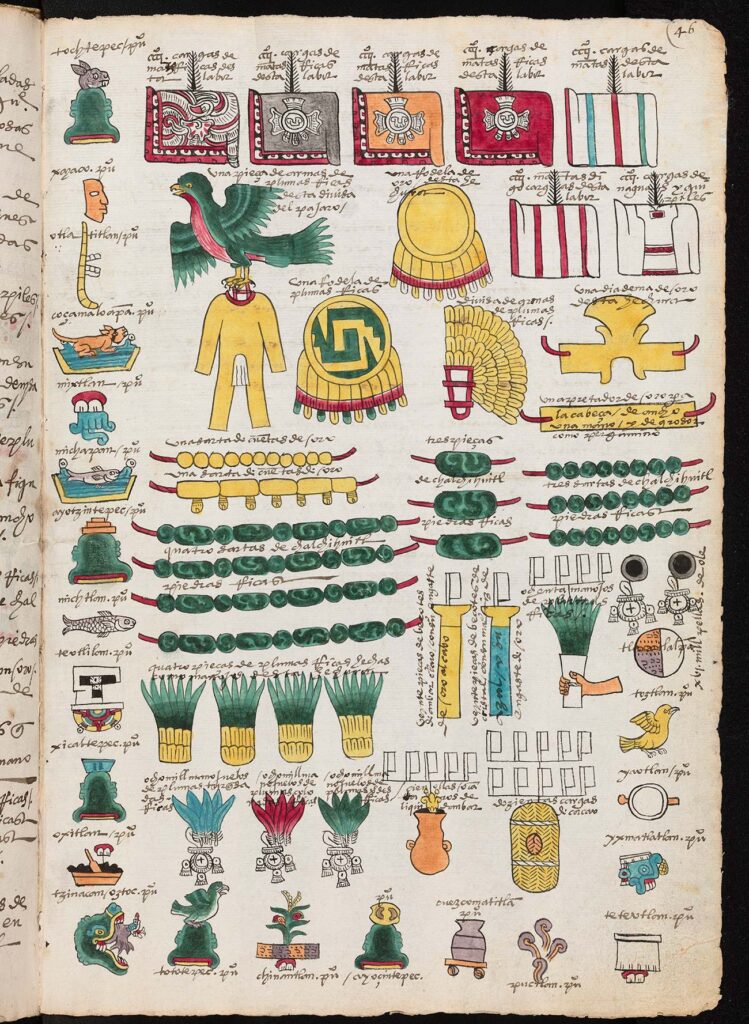

Codex Mendoza, 1542, possibly Francisco Gualpuyogualcal and Juan Gonzalez (artists), Nahua and Spanish culture, made in Mexico City (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Arch. Selden A.1)

Fascinating parallels emerge when looking at maps across cultures. The 11th-century “Book of Curiosities” from Egypt, for example, describes legendary peoples and creatures that also appear in a 13th-century European compendium of Latin texts. The Ottoman admiral-mapmaker Piri Reis and the Korean scholar Kwon Kun created maps that include portions of the Americas (Brazil and the Aleutian Islands of present-day Alaska, respectively).

Bestiary, 1277 or after, made in Thérouanne (Flanders), present-day France. Tempera colors, pen and ink, gold leaf, and gold paint on parchment, 9 3/16 × 6 7/16 in. (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 4, 83.MR.174, fol. 120)

Mapping can also take many forms. On the Shoshone-Bannock Map Rock in Idaho, for example, Indigenous mapmakers charted astrological and geographic information onto the surface of rocks. The 1542 Codex Mendoza features a Nahua map of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan and visualizes the tribute from the provinces as luxury items of jade and feathers.

Piri Reis world map (detail), Isbantul 1513 CE / AH 919 (Istanbul, Topkapi Sarayi Museum, No. H 1824)

Through these and many other examples of maps, manuscripts, and related book arts, Toward a Global Middle Ages demonstrates that geographic and cultural boundaries were and are porous, fluid, and permeable.

Kangnido Map, 1402, copy from the late 15th century (Honkoo-ji Tokiwa Museum of Historcal Materials, Shimabara, Nagasaki prefecture, Japan)

Map Rock Petroglyph, Shoshone-Bannock People, Givens Hot Springs, Canyon County, southwestern Idaho, 1054 or later (photo: Rosemarie Ann and Kenneth D. Keene)

This essay first appeared on the iris (CC BY 4.0).