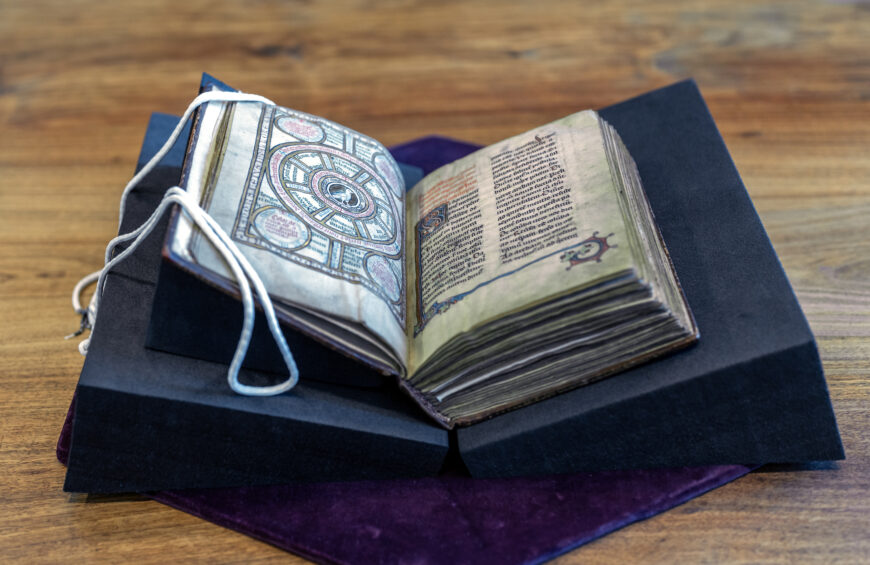

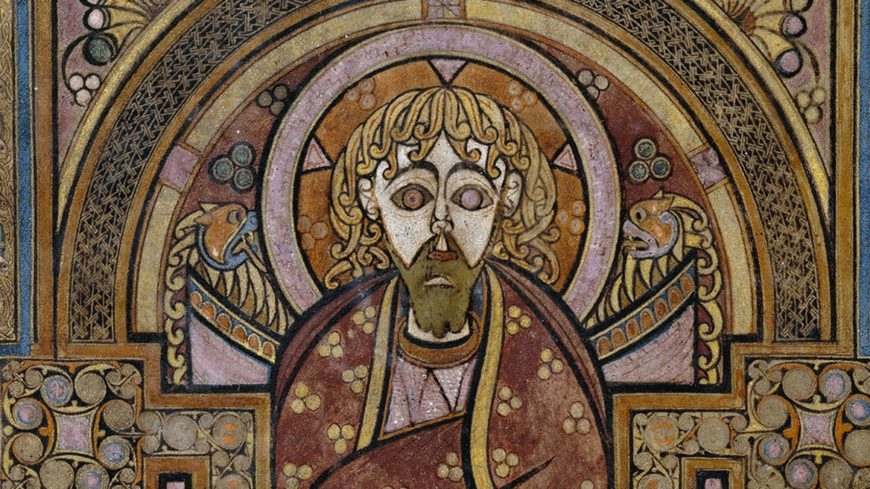

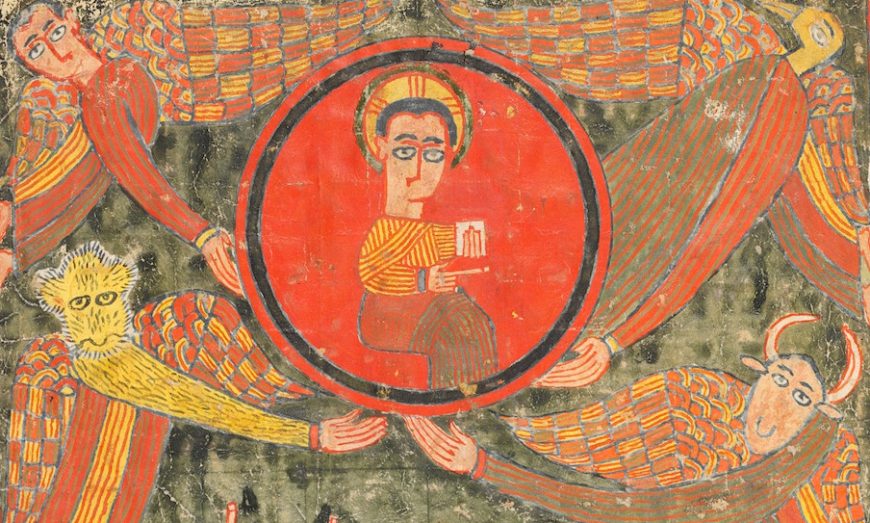

One of the oldest surviving bibles was made in England but has clear visual ties to traditions from the ancient Mediterranean.

Codex Amiatinus, before 716, Wearmouth-Jarrow, 50.5 x 34.0 cm (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, MS Amiatino 1). Speakers: Dr. Claire Breay, Head of Ancient, Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts and Dr. Beth Harris