Created at the end of the Byzantine Empire, this image looks back to the achievements of an earlier empress.

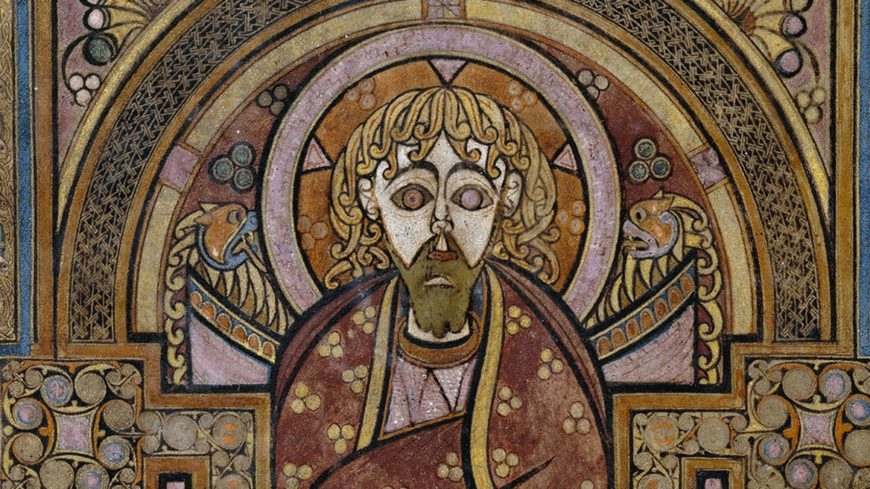

Icon with the Triumph of Orthodoxy, c. 1400 (Byzantine), tempera and gold on wood, 39 x 31 cm (The British Museum, London)

[0:00] [music]

Rachel Ropeik: [0:05] Here we are at the British Museum. We are looking at the “Icon of The Triumph of Orthodoxy,” which was made in about 1450 in Istanbul, not Constantinople, although it was Constantinople then. Because we’re still in the time of the Byzantine Empire when this was made.

Pippa Couch: [0:20] At that time.

Rachel: [0:23] I think what always grabs me the first about looking at icons is the contrast of the colors against the gold background.

Pippa: [0:31] Yes.

Rachel: [0:33] Makes the colors kind of seem that much more vibrant, but also it draws your attention to the gold background itself.

Pippa: [0:39] The gold, of course, is the spiritual. It’s the heaven. It’s what you’re not supposed to represent, because we’re looking at Byzantine art, we must remember that what happened was there’s a period, otherwise known as iconoclasm, where there was a war fought over images and image producing became completely illegal.

[0:55] People went around destroying icons, images, church imagery. There was a good 150 years where people couldn’t make art. They fought wars for it and they destroyed art because they felt that you shouldn’t be representing Christ in any way because of “Thou shalt not worship false idols” in the Bible.

Rachel: [1:10] So not that different from the Islamic idea of not representing figural folks.

Pippa: [1:15] The same idea from the same book, same words, exactly. What we have in this icon is very interesting. It doesn’t function simply like the traditional icon, where you look at it and you’re worshiping through it, you’re meditating on it and having it as a channel to the figure represented on the panel.

[1:30] This has also got some commentary about the history of icons itself. The name of this is the “Triumph of Orthodoxy,” and it’s split into two registers.

[1:39] If we look at the upper one, quite obviously there’s an icon within an icon in the middle. It’s being held by two angels, surrounded in red material.

Rachel: [1:47] So if they’ve been destroying images for a good long time there, then here is not only an image, but they’re showing an image within the image. They’re emphasizing that it’s OK now to paint these images again.

Pippa: [1:58] To the left-hand side we’ve got Empress Theodora. Her name is written above her there, identifying who she is. On the lower register, we have a whole list of figures there. You’ve got your priests and monks, and there’s one single woman on the left-hand side as well.

Rachel: [2:13] She’s holding a little tiny image. It looks like it’s Christ in there I think because it’s got…

Pippa: [2:17] Because you see it’s got the cross nimbus. That’s not just a normal halo, it’s got the cross in the background. That’s how you know that’s definitely Christ.

Rachel: [2:24] So we’ve got lots of images within images here.

Pippa: [2:28] This is an icon made in the 1400s with a load of people and an empress from 800.

Rachel: [2:34] Why are they looking back? What are they doing? It seems like the emphasis really is on that tradition of image making, and putting Theodora in there makes sense because she’s the one who was responsible for bringing back the tradition of images.

Pippa: [2:48] She’s restored image making. She was the one that brought about the triumph of orthodoxy, the fact that we could worship images again. It’s interesting, because the image in the icon within the icon there that the angels are holding is one of a type called the Hodegetria. It means “she who shows the way.”

[3:06] You see the way she’s holding her hand and she’s pointing to her son, the Christ Child on her lap. Look at her face. She’s sorrowful. She’s very sad and she’s, with her hand if you see, she’s pointing to him and her face is jumping ahead to what she knows is going to happen next, that he’s going to be crucified.

Rachel: [3:23] And it is a very common type of Virgin and Child that you see in icon paintings specifically.

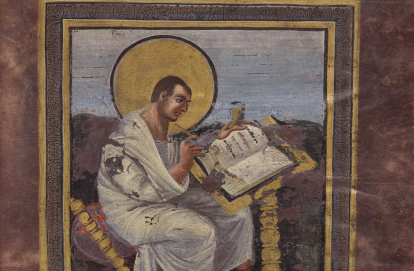

Pippa: [3:28] It’s very important, because the original version of this, they say, was painted by Saint Luke from life, from Mary.

Rachel: [3:35] Saint Luke the Evangelist of the Four Evangelists — Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This is Luke.

Pippa: [3:41] Yes, and he’s the patron saint of painters now, because of this. They said that this particular icon, the original one, that they said that Saint Luke had painted, was kept in Constantinople. They did lots and lots of copies of that icon. Each icon you copied would be the same more or less, but it would take the inherent property of the original one, that power that Saint Luke had put into it.

[4:02] The lower register, then, if we’re looking at the top when they’re celebrating the empress who brought this back on the upper register. To the lower register, we have this whole array as we said before of monks and saints and the lady on the left-hand side. They are all people who were martyred in the cause of trying to protect imagery during the iconoclastic years.

Rachel: [4:21] They’ve all got this kind of lovely beards, except for of course our one lady on the end. Look at all their robes as well, the kind of vertical lines of all these robes, kind of putting them into rank and making a unit of them. Like, look at all of the many people who’ve been martyred for this important cause.

Pippa: [4:37] The question again is then why in 1400 are they looking back to a scene from 843 that they’ve kind of composed? We know that maybe not all those martyrs would have been born at that time, some of them were martyred later on. Why would they do that in 1400?

Rachel: [4:52] Let’s think about what was kind of happening with the Byzantine Empire at the time.

Pippa: [4:56] It had reduced. They inherited the Roman Empire. It was vast. It’s reduced now to just basically the area we would now call modern-day Turkey. Of course, the Islamic people have been coming across and barraging them. Their faith doesn’t use imagery and they’re battering these people. And they’ve run out of wealth, they’ve run out of money at the Byzantine Empire.

[5:16] They’re going around and they’ve even coming to the courts in the West, of France, traveling great distances asking for support and money to help them fight these armies, and they say no.

Rachel: [5:25] This is, in a way maybe, trying to connect to a previous time in the Byzantine Empire’s past where they were stronger, and the image saved them.

Pippa: [5:36] With having all the help removed from them and other powers in Europe saying, “No, we’re not helping you, we’re not giving you money, we’re not supporting you.” They go back to, “Well, we better just try the images again.” So they make their special image, with an image of triumph and power and glory, and hope that that will save them from the onslaught.

Rachel: [5:51] It doesn’t really work, sadly. The Byzantine Empire doesn’t really survive. I’m struck by that emphasis on the power of image making and images themselves, because as art historians, that’s something we kind of continue to believe to this day.

Pippa: [6:05] The power that drove people to kill each other, because of the power of the image.

[6:09] [music]