Related works of art

In the Ancient Mediterranean

Masks

Active in c. 5000 B.C.E.–350 C.E. around the World

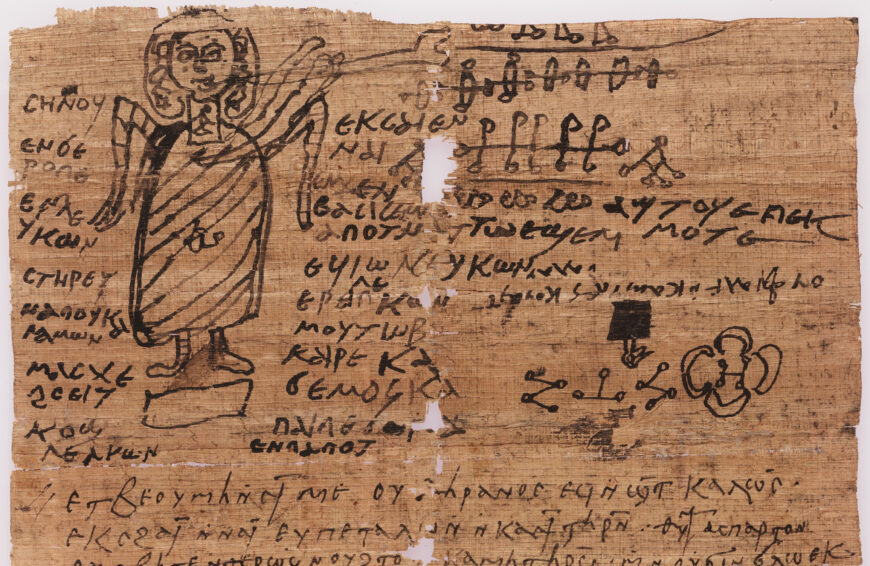

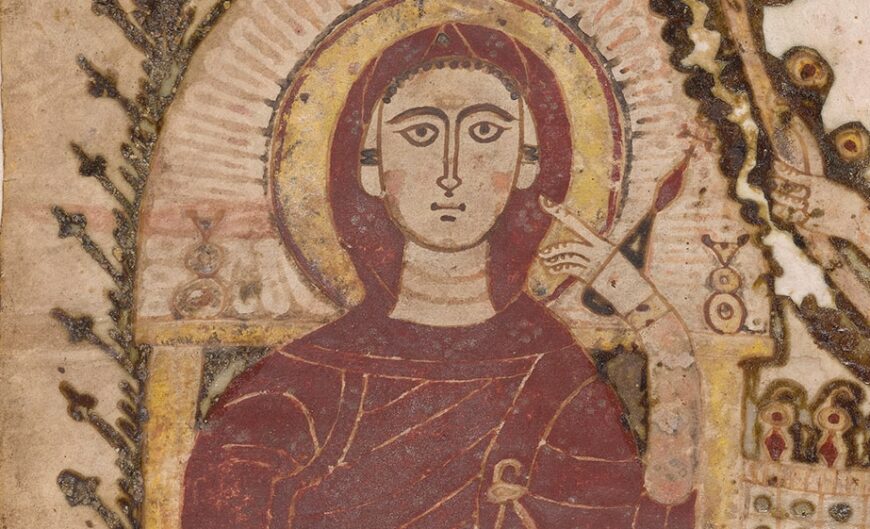

In North Africa

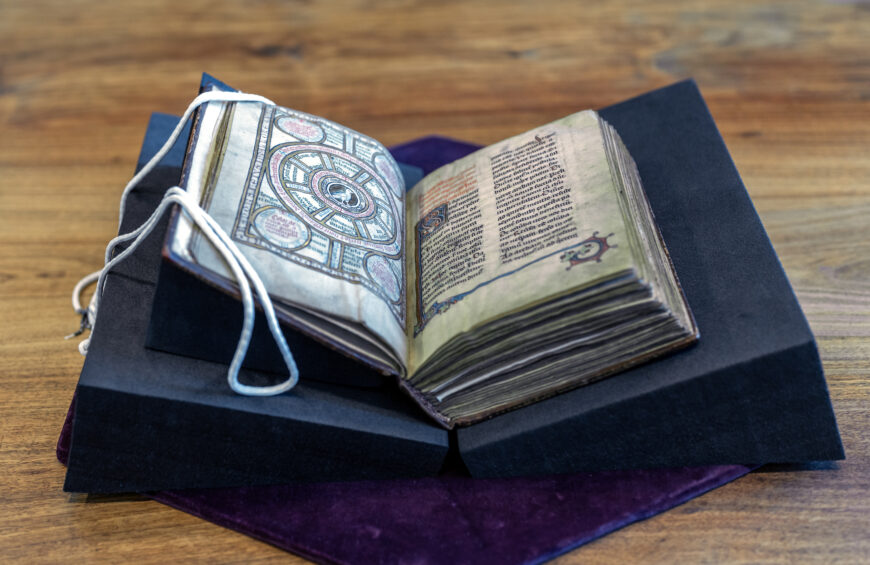

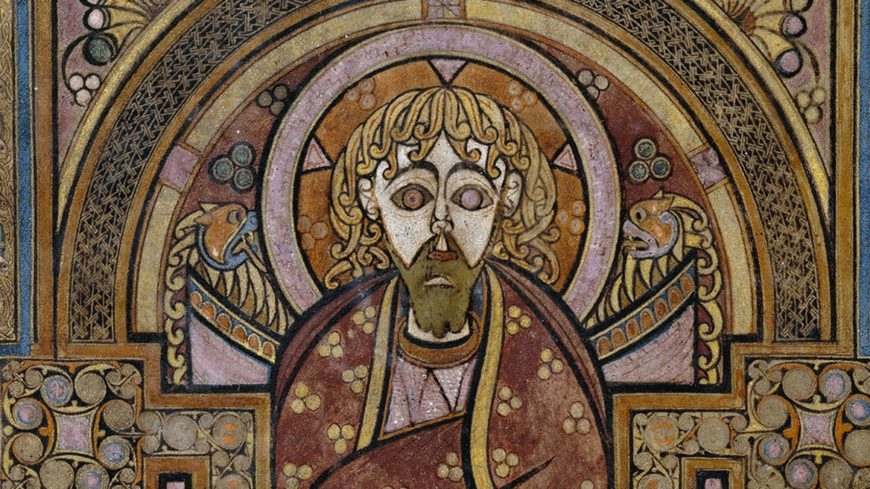

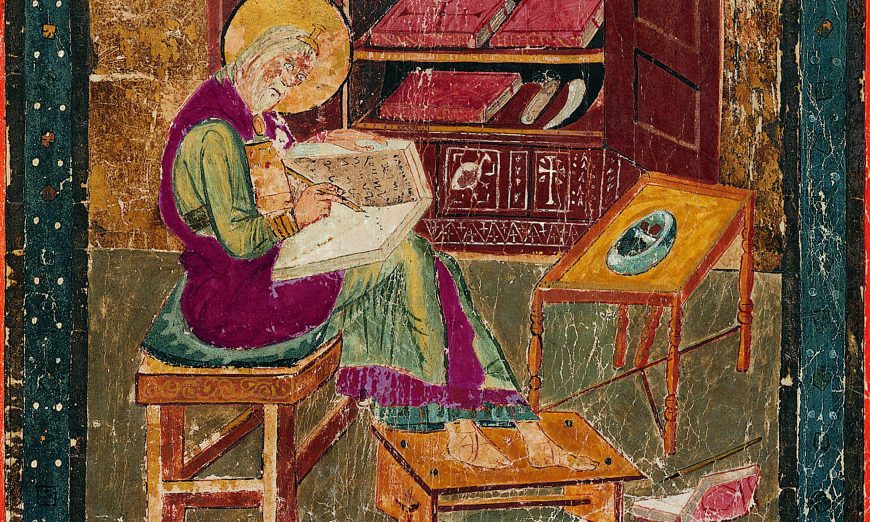

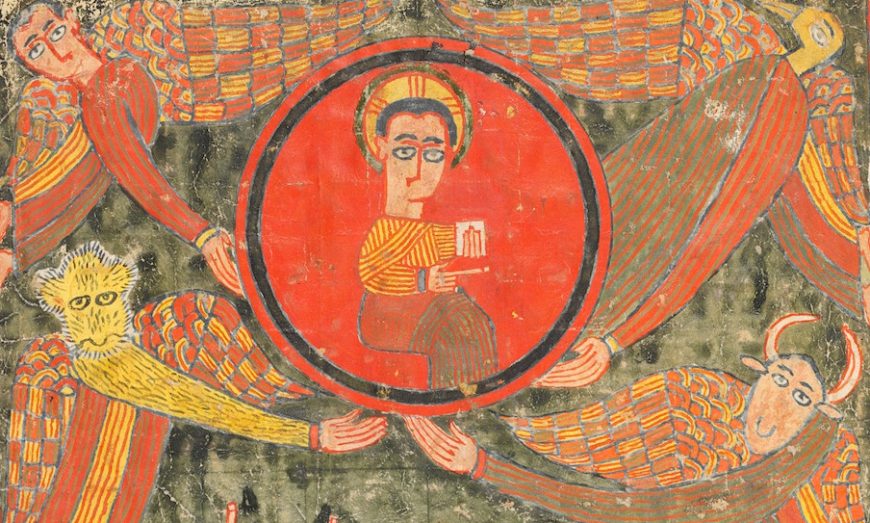

De Natura Avium; De Pastoribus et Ovibus; Bestiarium; Mirabilia Mundi; Philosophia Mundi; On the Soul

Getty Conversations

written and compiled in the late 12th century, manuscript produced in 1277 or after

France

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!