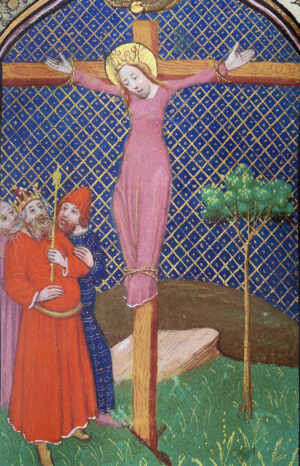

Saint Wilgefortis, Book of Hours and Psalter, c. 15th century, ink and gold on vellum (The University of Manchester Library, Rylands Collection, Latin MS 20, sheet 78)

Though you may have never heard of Saint Wilgefortis, she was once popular enough in Europe to rival the Virgin Mary. Religious reforms and controversies resulted in the destruction of shrines, paintings, and statues dedicated to her and she was almost forgotten. [1] The surviving artworks depicting her attest to a strong cult, especially in Central Europe in the early modern period. A great deal of Wilgefortis’s appeal lay in her specialty: relieving women of unwanted husbands. Images of Wilgefortis depict a crowned woman with a beard on a cross uncannily reminiscent of imagery of Christ on the cross. Sometimes there is little visual differentiation between Christ and Wilgefortis on the cross save a feminine dress.

A complex figure, Wilgefortis speaks to medieval and early modern understandings of gender beyond a simplistic binary and often undocumented histories of women suffering abuse. [2] Recent interest in Wilgefortis has been buoyed by interest in queer histories. In accordance with current scholarly literature, this essay uses female pronouns for Wilgefortis following medieval and early modern texts while recognizing textual pronouns are but one part of Wilgefortis’s legend.

Saint Wilgefortis, Book of Hours, c. 1440 (The Morgan Library and Museum, MS W.3, folio 200 verso)

Legend of Wilgefortis

The legend seems to have appeared around the 14th or 15th centuries. With the exception of the facial hair detail, the legend follows standard virgin martyr tropes. Wilgefortis was a princess, the daughter of the pagan king of Portugal. She had converted to Christianity and taken a vow of virginity. She expressed a desire to be married only to Christ himself and remain a virgin bride her whole life. Wilgefortis resisted the marriage her father had arranged with the king of Sicily. Enraged, her father imprisoned his daughter. In some versions of the story, he tortures her as well. Wilgefortis prayed for a physical transformation that would render her too unattractive for marriage. Miraculously she grew a beard and the King of Sicily withdrew from the betrothal agreement. At this point, the King of Portugal decided to crucify his bearded daughter. During her crucifixion, Wilgefortis prayed that those who remembered her martyrdom be delivered from their burdens. Wilgefortis has been considered a patron saint of prisoners, the ill, soldiers, female health issues (including childbirth and uterine cancer), sexual abuse survivors, and women trapped in bad relationships.

Wilgefortis’s role as a saint who frees people from their burdens is expressed in the variety of names by which she is known. In Dutch she is known as “Ontcommer” and English “Uncumber,” monikers that literally name the saint as an “unencumberer.” Some French cults of the saint referred to her as “Débarras,” from the verb “débarrasser,” meaning “to get rid of.” The Tyrolian name Kümmernis likely derives from the German word “Kummer,” meaning “grief” or “sorrow.” Wilgefortis might be a German transliteration of the Latin “virgo fortis,” meaning “strong virgin,” or alternatively from the German “hilge vratz,” meaning “holy face.”

Volto Santo, c. 770–880, polychrome wood and gold, 2.4 m high (Cathedral of San Martino, Lucca; photo: Holly Hayes, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Like Christ

In visual art we typically see Wilgefortis in a standing position affixed to a wooden cross, often wearing a crown. Shoulder-length hair and a beard heighten the comparison to Christ. Her calm demeanor is suggestive of the Christus triumphans type of crucifix, with the iconography of Christ standing upright rather than sagging. In this form, Christ stretches his own arms into the familiar T shape rather than hanging on the nails affixing him to the cross, emphasizing Christ’s triumph instead of his suffering, and his voluntary acceptance of the crucifixion. [3]

An example of the Christus triumphans crucifix can be seen in the famous miracle-working wooden Volto Santo (Holy Face) crucifix housed in the Cathedral of San Martino in Lucca, Italy in which Christ appears alive, standing, crowned, and wearing robes of kingship and priesthood. This figure’s attire already appeared somewhat feminine to late medieval viewers. The additional clothes, ornaments, and shoes added to the sculpture for special feast days furthered the perception that the statue might portray a woman. [4] It’s possible that the cult of Wilgefortis, the crucified bearded princess in a crown, emerged from devotional practices around the Volto Santo (supporting their connection of Volto Santo and Wilgefortis is a legend associated with them both that involves a musician and the gift of a golden shoe).

Saint Wilgefortis, c. 1750–1800, wood, 254 cm high (Museum of the Diocese Graz-Seckau, Graz; photo: Gugganij, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Wilgefortis’s similarity to Christ in art visually expresses broad medieval and early modern Christian cultural understandings of gender and the divine. The princess saint grows a beard and becomes more Christ-like in advance of her crucifixion that imitates Christ’s own. [5] The beard was not perceived as a transgression of femininity, but rather as confirmation of her holiness. Since medieval and early modern Christian European culture viewed masculinity as superior to femininity, we might expect praise for women saints who imitated Christ by performing masculine actions. The Virgin Mary and some female martyrs were praised for what were perceived to be manly virtues. What might be more surprising are historic ideas concerning Christ’s feminine qualities.

Medieval Christian writings often attributed feminine qualities to Christ’s body. Mystical interpretations of Christ’s side wound likened it to a vulva and vaginal opening, associating Christ’s life-giving blood with the life-giving blood of childbirth. His body was understood as both male and female: male as the son of God, female as flesh made by the body of his mother Mary. [6] Wilgefortis’s dual masculine and feminine qualities only enhanced her laudable imitation of Christ.

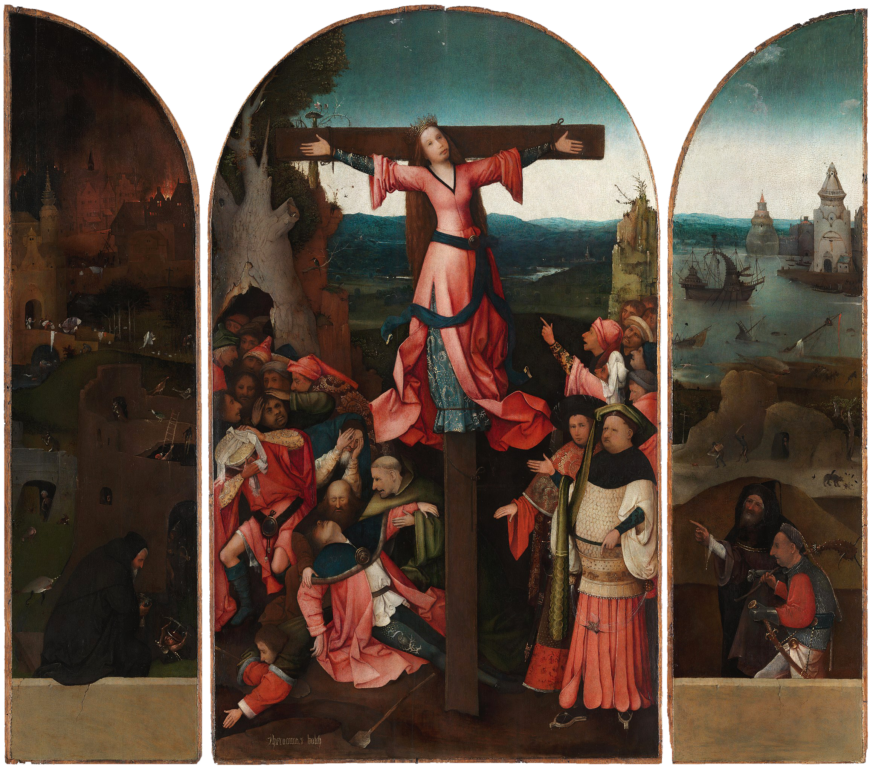

Hieronymus Bosch, The Crucifixion of Saint Wilgefortis, c. 1497, oil on panel, 104 x 119 cm (Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice)

In the cultural context of European Christian thought, Wilgefortis was not anomalous. The visual arts present her as a serious figure without sensationalizing her possession of a beard for spectacle—no circus “freaks” here. [7] Even Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych depiction—recently recognized as portraying Wilgefortis—presents the saint in markedly feminine attire with long hair and a light beard, keeping the focus on the martyrdom of Wilgefortis rather than playing up her facial hair. In an anonymous 18th-century German painting, Wilgefortis stands on a pedestal with only a horizontal beam suggesting a crucifix behind her. Her beard matching her hair color exists simply on her face. The same straightforward presentation can be found in the earlier images. The 15th-century Morgan illumination depicts Wilgefortis’s angry father in red shaking a scepter at his daughter high on the cross, but the saint herself is presented serenely, bearded, gazing down at her father. Images of Wilgefortis contrast with sexualized images of female saints who were stripped (Saint Catherine in the Belles Heueres) or faced sexualized torture (Saint Agatha whose breasts were removed with pincers).

Wilgefortis now

Wilgefortis was never officially canonized by the Catholic Church. In 1969, following Vatican II, her feast day was removed from the Catholic calendar. Nevertheless, she was an important saint to many people centuries ago—and recently too. LGBTQ+ communities in particular have embraced Wilgefortis as a testament to queer histories and queer holiness. Contemporary artists continue to find Wilgefortis fascinating; for example, queer Chicana artist Alma Lopez included Wilgefortis in a “Queer Santas: Holy Violence” series she painted in the 2010s. [8] A news article about the exhibition asked, “Were some Catholic saints transgender?”

Art historians ask instead, “how did people relate to the figure of Wilgefortis and what can we learn about that through the history of art?” As with all culture, especially cultural figures that have remained relevant over time, there is no ultimate determination that can define what Wilgefortis is or was historically. As art historians, we describe how a symbol, story, or figure functioned in a culture and how people responded with historical practices. Cultural responses change over time as do understandings and beliefs. What can be said with certainty is that Wilgefortis’s gender expression outside of a strict gender binary formed a fundamental aspect of her appeal in the medieval and early modern periods and continues to generate interest in the figure today.