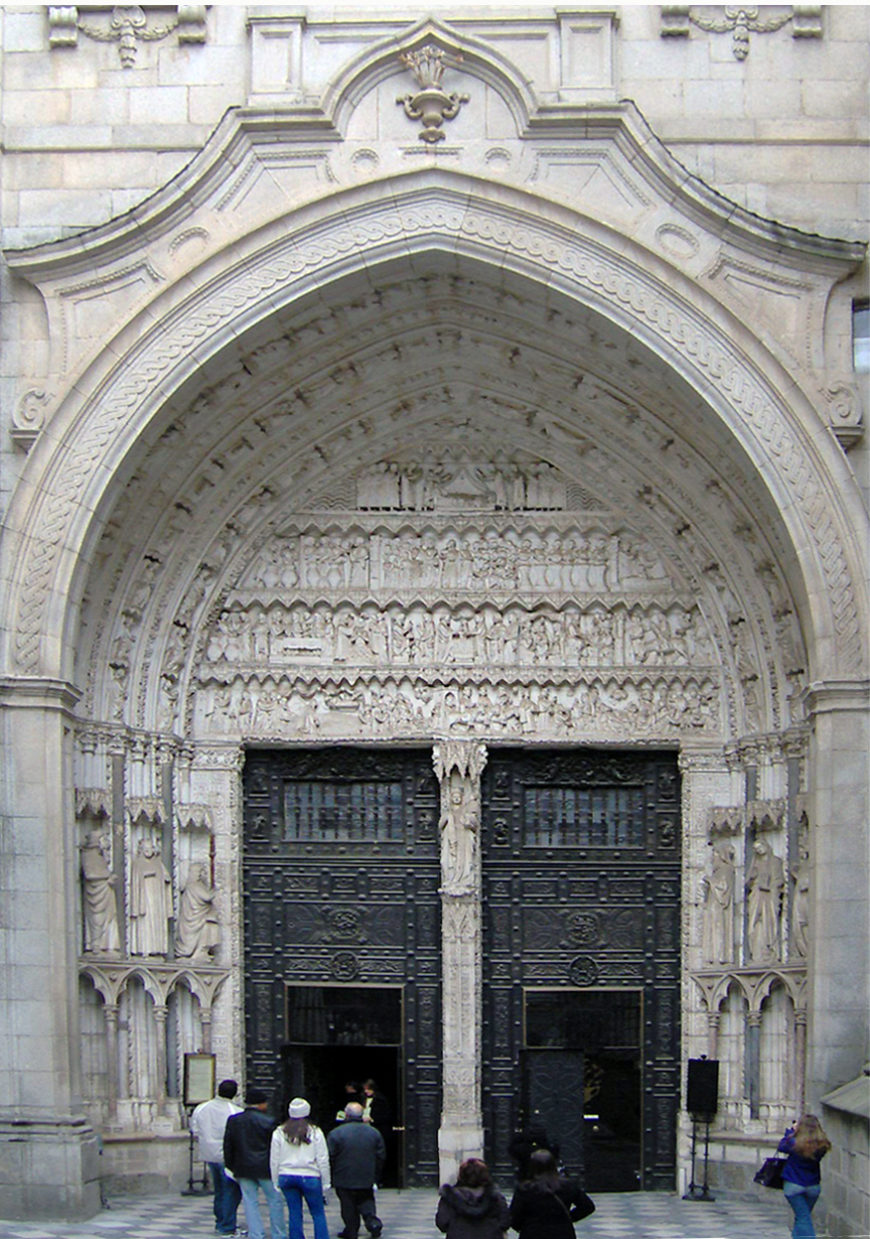

Toledo Cathedral, begun in 1227, Toledo, Spain (photo: Nikthestunned, CC BY-SA 3.0)

When Archbishop Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada decided to rebuild Toledo Cathedral in 1227, he knew that he was setting into motion something important. He was beginning construction on Spain’s first Gothic cathedral, and he made sure his actions would be remembered. In a chronicle he wrote, that details the history of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal today) from ancient times, he stated:

And the king and Archbishop Rodrigo placed the first stone in the foundations of the church of Toledo, which still remained in the form of a mosque from the times of the Arabs; its form was raised over many days, not without the great admiration of men. [1]

Like many major cities on the Iberian Peninsula, Toledo was in Islamic hands for many centuries after Umayyad forces conquered this area in 711 from the Christian Visigoths. It was several hundred years later (in 1085) when King Alfonso VI captured Toledo and it passed back into Christian hands. For the next 142 years, the city’s cathedral was housed in the Friday mosque (main mosque of an area that hosts Friday prayers) built by the city’s former Islamic rulers.

Toledo Cathedral, begun in 1224, Toledo, Spain (photo: Pedro, CC BY 2.0)

When Rodrigo began constructing a new cathedral, he was tearing away one of the most potent symbols of Toledo’s Islamic past and replacing it with a new style associated with France: a Gothic cathedral. Toledo Cathedral’s size, decorations, and treasury were unmatched by few other buildings constructed at the time—whether in Iberia or the rest of Europe.

In the following centuries, many other cities in Iberia rebuilt their cathedrals in the Gothic style, always fusing foreign French influences with local artistic traditions.

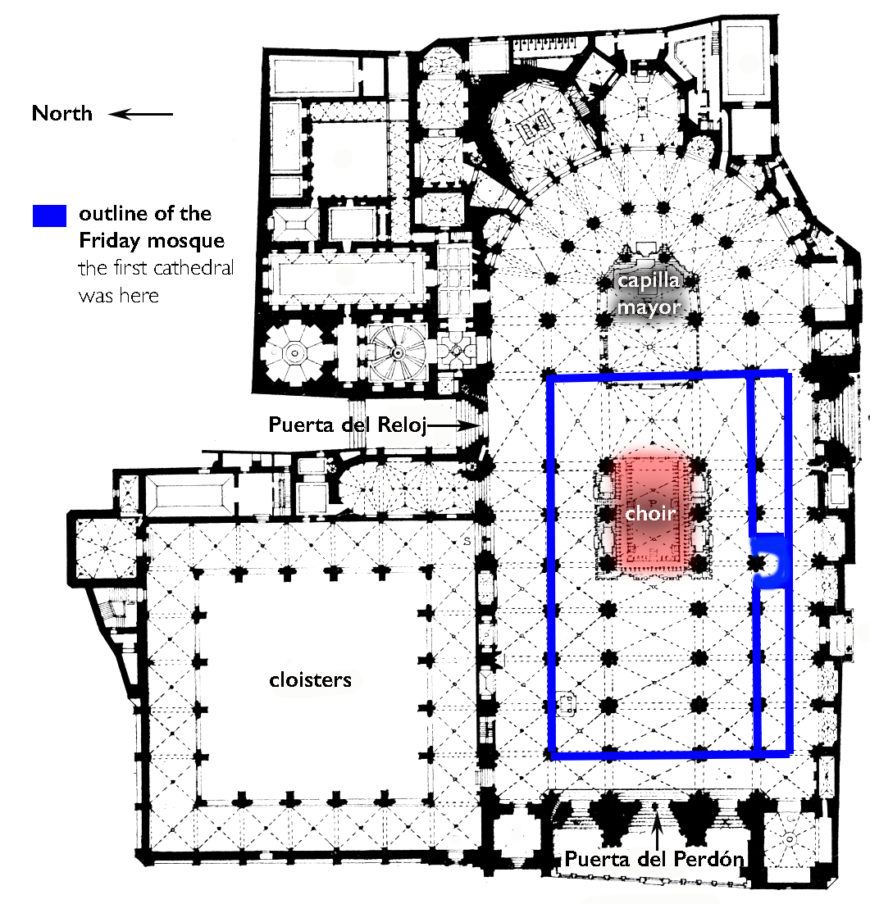

Plan of Toledo Cathedral as rebuilt in the Gothic style. Blue outlines indicate the former mosque. The mosque structure was repurposed for the original cathedral (before it was rebuilt in the Gothic style).

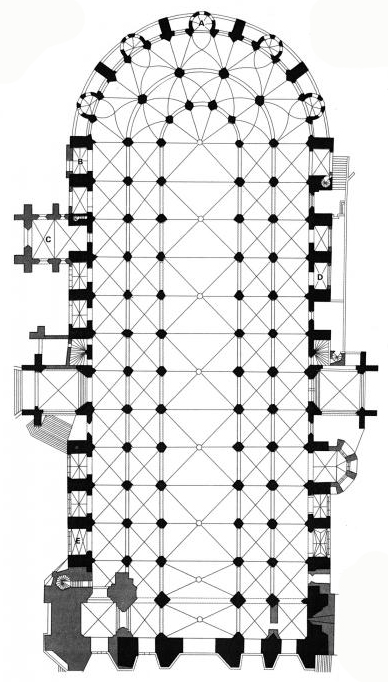

Ground Plans

Many Gothic cathedrals in Iberia— not just Toledo’s—were constructed over the remains of their city’s Friday mosque, and this left a lasting impact on the shape of cathedrals’ structure. When a cathedral replaced a mosque, it was typical for the new building to be very wide because it followed the footprint of the preceding mosque. For example, Toledo Cathedral is as wide as the mosque was—59 meters—and its cloister was built within the confines of the mosque’s ṣaḥn (courtyard). This was also the case with other cathedrals in Zaragoza, Valencia, Seville, Jaén, and Murcia.

Though built over the remains of mosques, these buildings were emphatically Gothic cathedrals and they followed many of the conventions established in France. Archbishop Rodrigo traveled to France around the year 1200, and saw firsthand the new architectural style at places like Notre-Dame in Paris. He even visited the birthplace of the Gothic style, the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis just north of Paris. What he saw there influenced how he rebuilt Toledo’s cathedral. It is likely that he had a French architect design the new cathedral. As in France, building a cathedral took considerable time and at Toledo, it took more than 100 years to complete. As a result, Spanish Gothic cathedrals can reveal how tastes changed, and how structures evolved over time. At Toledo Cathedral, for instance, many additions and alterations from the 14th century onward have changed its appearance.

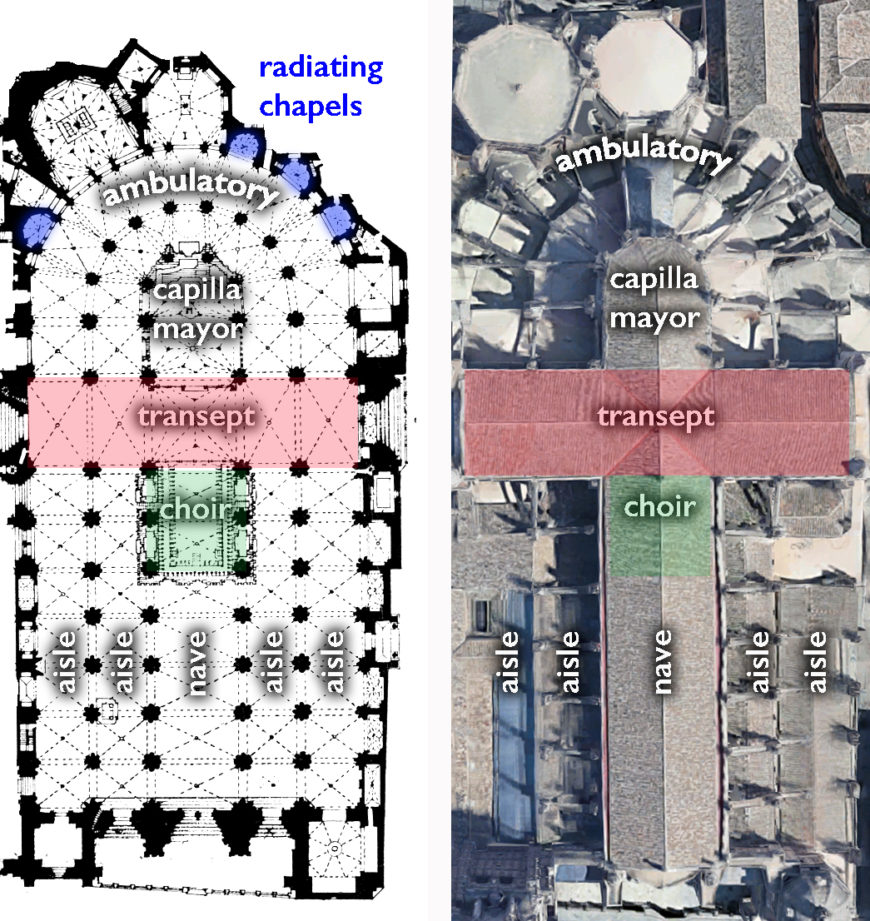

Plan of Toledo Cathedral with aerial view of the cathedral (underlying image of the cathedral © Google)

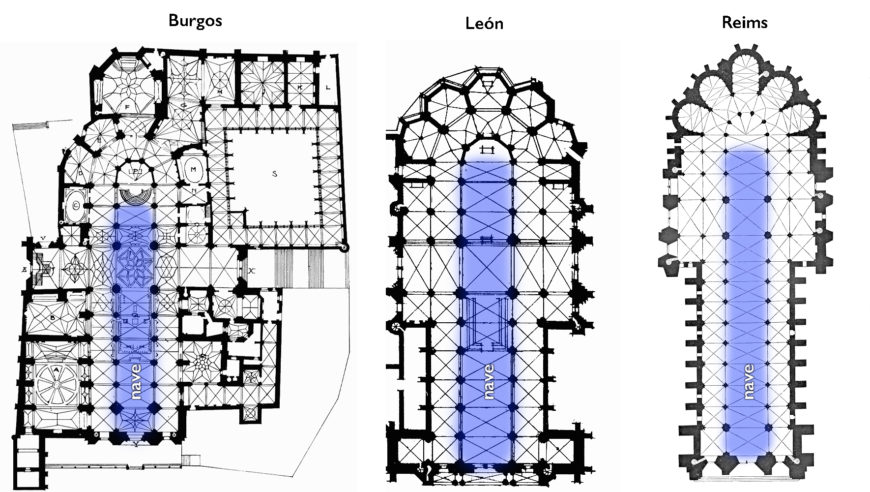

Like most Gothic cathedrals, Toledo Cathedral is made up of a long nave, a transept (a second long hall that crosses the nave), as well as a semi-circular space at the east end called the apse (the high altar is also located at the east end of the church). The ground plan is reminiscent of Saint-Denis in the double aisles and continuous ring of chapels (radiating chapels) around the apse (off the ambulatory). Toledo Cathedral also closely followed the ground plan of Bourges Cathedral, with a sleek outline created by short transept wings.

The Choir and the capilla mayor

Despite the clear influence of French Gothic churches on Spanish cathedrals, many of the cathedrals built on top of old mosques share an unusual feature for a Gothic church: the choir (the enclosed space reserved for the clergy during services) is located in the nave.

In the typical French Gothic cathedral, the choir is commonly located in the apse at the furthest eastern end of the church (although there are exceptions, such as at Reims). Iberian cathedrals instead often have their choir west of the transept in the nave, more in the center of the church such as we see if we look at a ground plan of Toledo Cathedral. This plan can be seen in earlier Romanesque churches such as St. Sernin in Toulouse.

Some believe this may be the consequence of using converted mosques as churches. Mosques were not oriented in the same direction as churches and, as a result, when they were initially consecrated as churches (as Toledo’s cathedral had been after 1085), the high altar (the primary altar of a church) was often in a more central location in the building rather than at the east end of the church (as we see in the later Gothic building).

Later, when many of these churches were being transformed (and enlarged) into Gothic cathedrals, the decision to place the choir in the center of the nave was likely a practical one: it was located where the preceding church (and former mosque) was located. At Toledo, for instance, the altar of the Virgin had been the main altar in the converted mosque, but as the Gothic cathedral was built the altar was left in what became a choir altar (churches often have multiple altars).

The high altar and retablo mayor (begun 1498) in the capilla mayor, Toledo Cathedral, Toledo, Spain (photo: British Province of Carmelites, CC BY 2.0)

In the rebuilt Gothic church, the apse (the semicircular space at the east end) housed the capilla mayor (main chapel). This chapel was the site of the high altar; the earlier placement of the high altar was thus moved. The capilla mayor was considered the most sacred location in any church because it is where the most important rites—including the Eucharist—were performed. It would be distinguished from other chapels by its monumental retablo mayor (main altarpiece), though most retablos that survive today were produced centuries later during the Renaissance.

View from the right of the choir, looking at the space before the capilla mayor. Today, the screen closes off access to the capilla mayor. Toledo Cathedral, Spain (photo: Graeme Churchyard, CC BY 2.0)

In most Gothic cathedrals in Spain, this set-up often left a large open space between the capilla mayor in the apse and the choir in the nave in an area called the crossing (at the intersection between the nave and the transept). Congregants would gather in this space and watch the services taking place. While Gothic cathedrals elsewhere in Europe might block off visual access to the sacraments with large choir screens, Iberian devotees could see almost everything that took place in both the choir and the capilla mayor. Being able to more easily witness the miracle of transubstantiation—the bread and wine transforming into the body and blood of Christ during Mass—would have been a revelation for congregants. It was only in 1215 that transubstantiation was officially defined at the Fourth Lateran Council (a meeting of the Catholic Church), and afterwards an increased focus on the Eucharist ensued.

Some cathedrals—especially those not built on old mosques—followed the French model more closely. Both Burgos and León looked to Notre-Dame de Reims for their ground plan, which resulted in much longer apses. León originally had its choir in the apse, but both cathedrals would eventually follow the examples of their Iberian counterparts, and the capilla mayor would be located in the apse.

Vaulting at the crossing, Seville Cathedral, Seville, Spain (photo: Pom, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Decorating the Cathedral

Puerta del Reloj with tympanum of the life of Mary, 13th century, north transept, Toledo Cathedral, Toledo, Spain (photo: Johnbojaen, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Like Gothic structures throughout the rest of Europe, Iberian cathedrals were stunning in the richness of their ornamentation, from the delicate tracery (lace-like ornamental stonework) that framed stained glass windows to the figural sculpture that adorned the façades. The structure of the walls dissolved into sculpted bodies, painted glass, tracery, crockets. (stylized leaves applied to stonework), and stone interlace patterns.

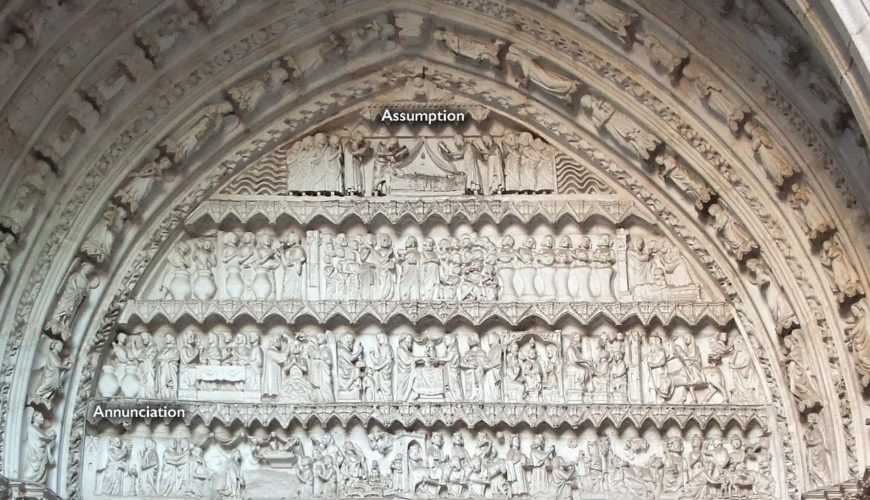

Large-scale statues of saints and biblical figures flanked the doors. Narratives from the Bible, Apocrypha (unofficial books of the Bible of questionable authenticity), or saints’ lives filled the space above. On Toledo Cathedral’s only remaining portal from the 13th century (Puerta del Reloj on the north transept), the tympanum (here a pointed semicircle above the door) is filled with four registers of countless bodies, creating a scrolling narrative that begins in the lower left with the Annunciation (when the Archangel Gabriel announces to Mary that she will bear the son of God) and ends with the Assumption of the Virgin (when Mary is assumed into Heaven) at the very top.

Tympanum, 13th century, Puerta del Reloj, Toledo Cathedral, Toledo, Spain (photo: Javi Guerra Hernando, CC BY-SA 4.0)

This sculptural imagery served a number of purposes. It marked the entranceway into the cathedral as the transition point between the mundane world outside and the sacred space within, encouraging churchgoers to enter a more devotional state of mind. It could also identify the most important saints and stories in local history.

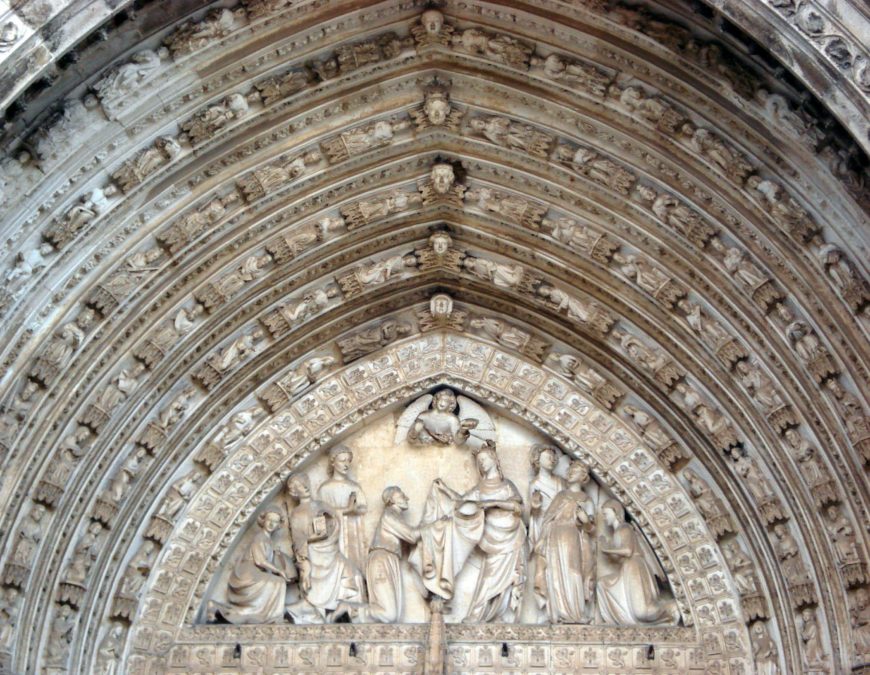

Puerta del Perdón tympanum, 14th century, west façade, Toledo Cathedral, Toledo, Spain (photo: MayaSimFan, CC BY-SA 3.0)

For instance, sculpted above an early 14th-century door (Puerta del Perdón) on the Toledo Cathedral’s west façade is the story of the Virgin Mary offering a miraculous garment to Saint Ildefonso, a 7th-century bishop from the city of Toledo.

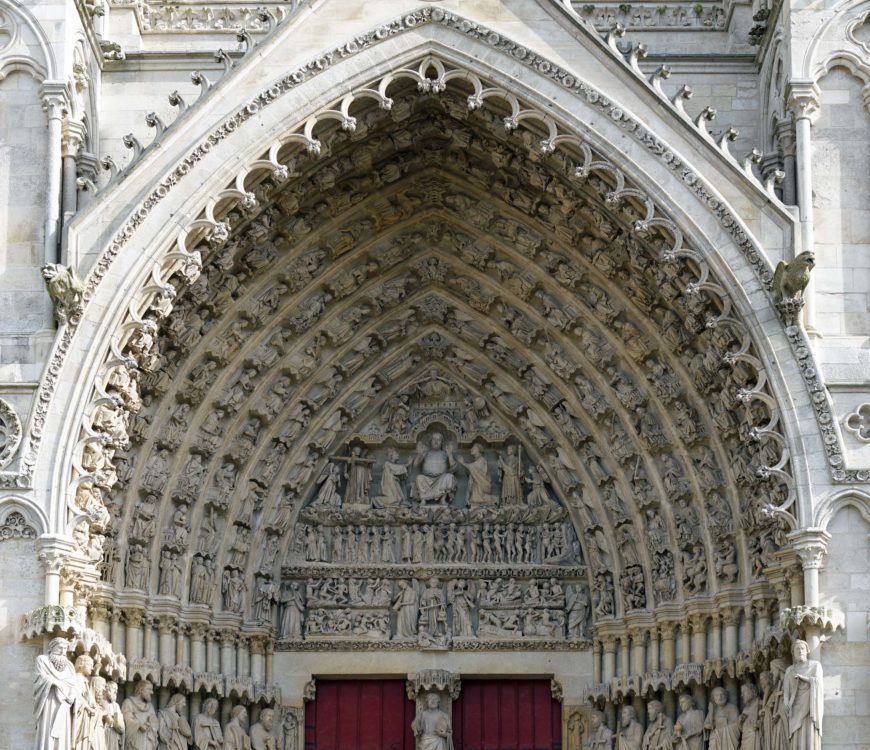

Puerta de Sarmental, 13th century, Burgos Cathedral, Burgos, Spain (photo: Coleccionista de Instantes Fotografia, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Central tympanum, Amiens Cathedral, Amiens, France, begun 1220 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Other 13th-century cathedrals, like Burgos Cathedral, took the sculptural programs of French cathedrals as their models. There, the Puerta de Sarmental’s tympanum shows Christ in Majesty (enthroned), surrounded by the Four Evangelists at work on their gospels and allegorical figures representing the seven Liberal Arts (studied at medieval universities), which closely follows the iconography of a portal at Amiens Cathedral. This entrance and its sculptural message were intended only for the bishop and clergy of the cathedral, which accounts for its more complex allegories.

Stained glass windows in León Cathedral, León, Spain (photo: Jcfll44, CC BY-SA 4.0)

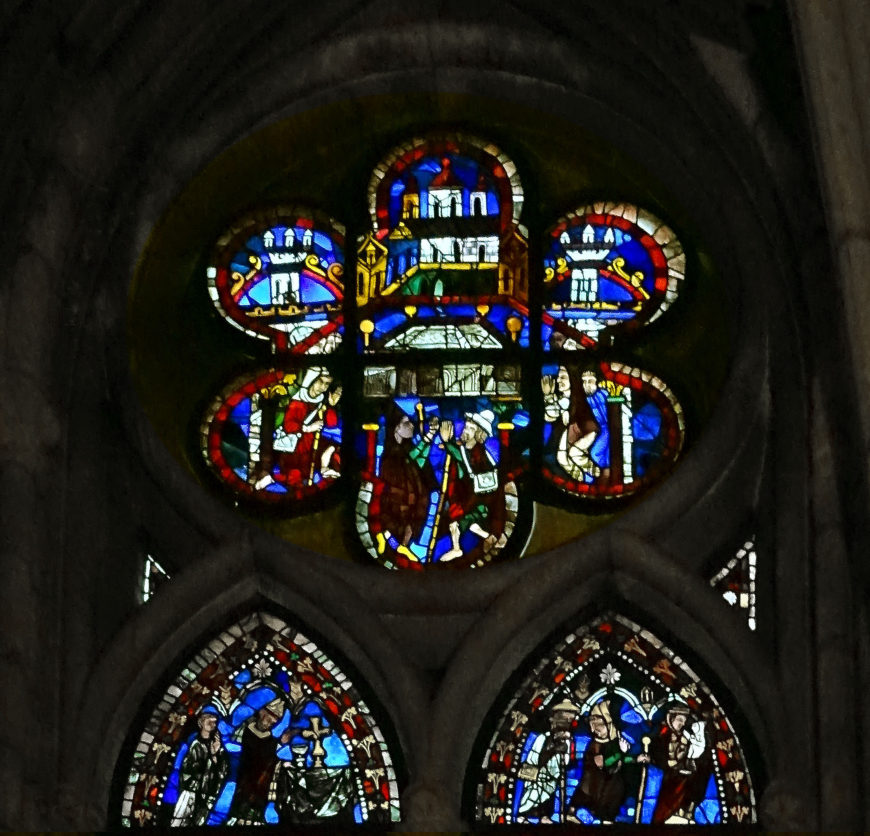

The introduction of the Gothic style into Iberia also came with the rise in popularity of stained-glass windows. Throughout the 13th century, many cathedrals filled their wide windows with colored and painted glass, although only León Cathedral has a substantial amount of medieval glass remaining. The thinning of a cathedral’s walls and the use of flying buttresses allowed for the use of larger windows of colored glass—such as we see in French Gothic cathedrals. In the chapels lining the perimeter of León’s cathedral are windows recounting events from the life of Christ or from the lives of well-known Iberian saints, like Saint Ildefonso. One rosette shows a group of pilgrims at Santiago de Compostela, the most popular pilgrimage destination of the Middle Ages (following Rome). Located in the northwestern region of Galicia in Spain, this was thought to be the resting place of the Apostle Saint James (Santiago in Iberia, revered in part for performing miracles of healing and for aiding soldiers in battle against Islamic forces).

Rosette showing pilgrims, Capilla del Nacimiento, León Cathedral, León, Spain (photo: Francisco Javier Guerra Hernando)

In this stained glass window, we see the Romanesque towers of Santiago de Compostela’s cathedral at the top, while in the middle is a long white casket, containing the saint’s relics. Clustered around the tomb are groups of pilgrims. They carry the staffs and satchel bags ornamented with a seashell that identify them as pilgrims of Santiago. Most kneel and clasp their hands in prayer as they look reverently towards the saint’s relics. Another pair appears to have just arrived, stepping forward to behold the tomb. Windows like this reveal the most important devotional figures and experiences in medieval Iberia.

Tower (Giralda), Seville Cathedral, Seville, Spain (photo: Howard Lifshitz, CC BY 2.0)

Even as the Middle Ages drew to a close, the Gothic style first introduced at Toledo Cathedral continued to be the most popular form for cathedrals in Iberia. In Seville, the process of demolishing the original mosque and rebuilding in the Gothic style began in 1401 and did not conclude until the early 16th century. Yet even then, the unique multicultural environment of Iberia had an impact on the structure. Following the placement of the altar in the old mosque structure, there was still the separation of the choir and the capilla mayor.

Tower (Giralda), Seville Cathedral, Seville, Spain (photo: Miamireader, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Parts of the old mosque’s courtyard were incorporated into the cloister walls, and the majority of the old minaret (tower used for the Muslim call to prayer) was incorporated into the cathedral’s bell tower. Then, as in the 13th century, a fusion of cultural styles came together in a uniquely Iberian Gothic cathedral.