This mosaic shows how the arts—and an interest in naturalism—flourished in the final centuries of the Byzantine Empire.

Deësis (Christ with the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist), c. 1261, mosaic, imperial enclosure, south gallery, Hagia Sophia, Istanbul. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:12] We’re looking at a mosaic that dates from the late Byzantine period, from the 1200s, but it’s in a church, Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, that dates to the 500s, the very beginning of the Byzantine period.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:20] We normally think about a building and its decoration dating from the same period, but we also know that we decorate our own homes. We’re familiar with that idea.

Dr. Zucker: [0:34] Now, it’s important to know that this mosaic, which is just glorious, was actually covered up for a very long time because this church became a mosque. When it became a mosque, all of its images, all of its crosses, were either removed or were covered.

Dr. Harris: [0:44] It’s wonderful to see it, but it hasn’t survived very well.

Dr. Zucker: [0:47] We only have about one-third left of this mosaic.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] Luckily, we have the faces of the three figures.

Dr. Zucker: [0:53] This is called the Deësis. It shows Christ in the center with his right hand blessing, his left hand holding the gospels. He’s flanked by the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist.

Dr. Harris: [1:04] That’s what Deësis means. This is a subject that we see often in Byzantine art.

Dr. Zucker: [1:08] It’s an intercession. That is, both of these figures are coming to Christ on behalf of mankind.

Dr. Harris: [1:13] It’s really easy to see the appeal of this medium. Small pieces of glass, some with gold in them, some colored.

Dr. Zucker: [1:21] These are tesserae. What’s fabulous about them is they’re set in the wall at slightly different angles. They all catch the light in different ways.

Dr. Harris: [1:29] The artist has created a pattern in the background of that gold that also catches the light.

Dr. Zucker: [1:35] Now, this is a massive mosaic. These figures are much larger than life. It’s also fairly high off the ground. They really do stand above us. That gold ground reminds us that this is a heavenly space. This is not an earthly space. They are distant from us but they’re also proximate. We feel as if there is an emotional connection.

Dr. Harris: [1:54] There’s an abstraction to the background. We see no landscape. We see no architectural setting. The face is carefully modeled, especially of Christ. The artist has used light and dark to create a sense of three-dimensionality in the face and in the neck and the hands of the figures.

[0:00] That’s also true of Mary and John, though perhaps to a lesser extent.

Dr. Zucker: [2:19] There are still these striations, that is, the use of line and the drapery to define the folds. It is still a kind of drawing as opposed to a modeling.

Dr. Harris: [2:24] Christ seems to look directly out at us and seems to be in the middle of raising his hand for that blessing.

Dr. Zucker: [2:34] It’s interesting because he does look up, but the other two figures are bowed. There is a solemnity, a kind of quiet.

Dr. Harris: [2:37] Both of those figures would have had their hands forward in gestures of prayer. Now, we’re in the 1260s here, and this is just after a very tumultuous period, to say the least, in Byzantine history.

Dr. Zucker: [2:55] This church, which was the heart of the Eastern Orthodox tradition, had been controlled briefly by the Latins, that is, by the Roman Catholics, the Western Church.

Dr. Harris: [3:00] In 1204, during the Fourth Crusade, as the crusaders were heading toward Jerusalem, they stopped and instead sacked the very wealthy city of Constantinople.

Dr. Zucker: [3:11] It was a terrible event and there was tremendous violence and really long-term scarring. Some historians look at that moment, the Fourth Crusade, as the moment of the long downward spiral of Constantinople.

[3:22] Nevertheless, after the Byzantines reclaimed their city, there were a couple of hundred years of a real flowering, and this mosaic is one of the great expressions of that period, which some even call a renaissance.

Dr. Harris: [3:39] This is a great example of late Byzantine work. It might even remind us of what’s going on in Italy at the same time with artists like Duccio.

Dr. Zucker: [3:46] Look at the elongation of the bodies. It’s not naturalism, for all of its emotional engagement. These are tremendously elegant figures. Look at the lengthening of the faces, of the nose, of the fingers.

Dr. Harris: [3:55] Elegant, but also emotional. Look at St. John. There is an awareness of the terribleness of Christ’s suffering on behalf of mankind.

Dr. Zucker: [4:04] I think this is a gorgeous mosaic, but in some ways, it feels out of place. It’s important to remember that, when this church was first consecrated, its extensive mosaics were not figurative. They didn’t show the Virgin Mary, and Christ, and St. John.

[4:19] They showed abstract symbols of the cross or patterns. In some ways, they really emphasized the structural forms, the volumes of the building as opposed to pictures on its walls.

Dr. Harris: [4:32] We know that there was tension around the use of images from the very beginning of Christianity. Do you picture Christ? Do you picture Mary? We know that in the Judaic tradition that was disallowed.

[4:44] On the other hand, looking at this image, I can see the incredibly profound value of images in aiding prayer, in helping one to engage with the divine and the transcendent.

[0:00] [music]

The route and results of the Fourth Crusade (Kandi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Constantinople, lost and reclaimed

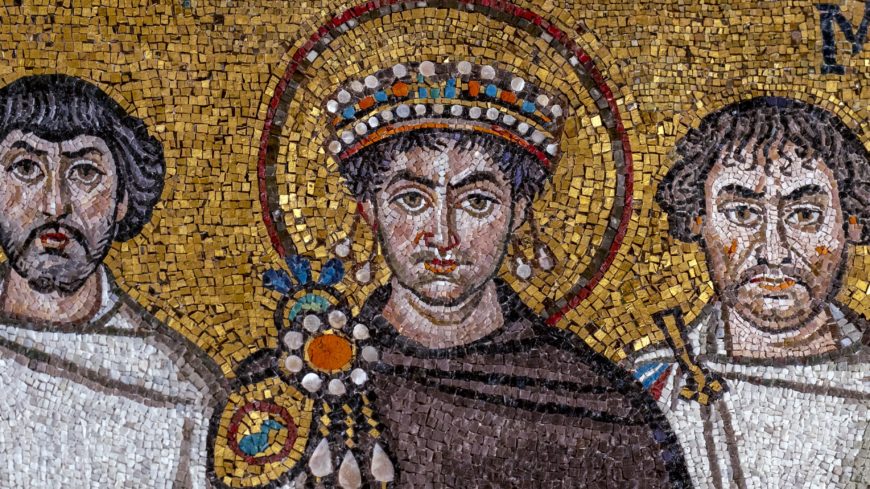

In 1204, a momentous event forever changed the history of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire. Western Europeans embarking on the Fourth Crusade diverged from their path to Jerusalem and sacked and occupied the Byzantine capital of Constantinople (modern Istanbul). The crusaders established a “Latin Empire” in Byzantine territory and subjected Byzantine Christians to the religious authority of the Pope in Rome. The crusaders also converted Hagia Sophia—Constantinople’s great cathedral, built in the sixth century by emperor Justinian—into a Latin (Catholic) church.

Isidore of Miletus & Anthemius of Tralles for Emperor Justinian, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), 532–37 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In 1261, the Byzantines recaptured their capital and crowned Michael VIII Palaiologos as emperor, inaugurating what historians refer to as the Late Byzantine—or Palaiologan—period. A new Orthodox patriarch of Constantinople was enthroned in Hagia Sophia in September 1261, and Justinian’s great church was used for the Byzantine rite once again.

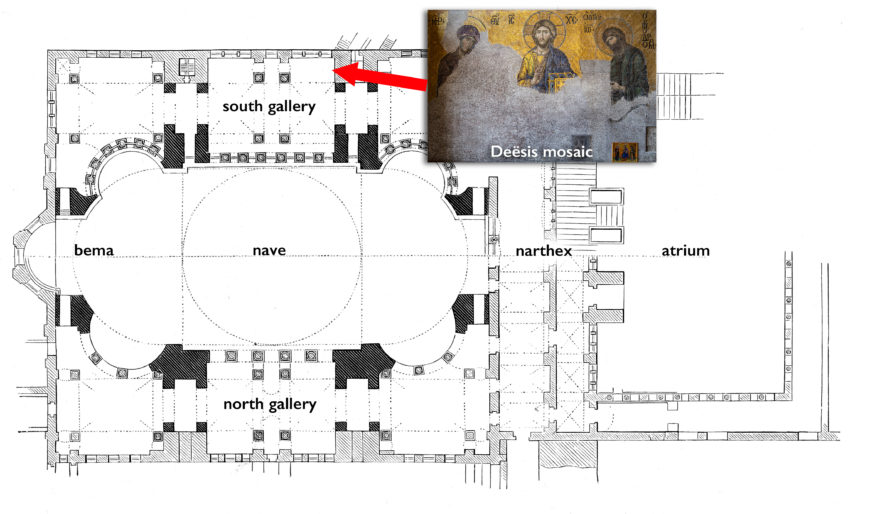

Location of the Deësis mosaic on the western wall of the central bay of the south gallery of Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul)

The Deësis mosaic in Hagia Sophia

Under Latin occupation, the capital and many of its churches fell into disrepair, and so the Byzantines began restoring Constantinople and its churches. Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, responsible for reclaiming the Byzantine capital, is likely responsible for installing a monumental new mosaic of the Deësis in the south gallery of Hagia Sophia—a part of the church traditionally reserved for imperial use—not long after reclaiming Constantinople in 1261. The mosaic was probably part of a larger restoration project in the church of Hagia Sophia.

Deësis mosaic, c. 1261, 5.2 x 6 m, south gallery, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The monumental Deësis mosaic depicts Christ flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist approximately two and a half times larger than life. The looming stature of these three figures reflects their importance in Byzantine culture. Christ, the Son of God, appears at the center of the composition and is labeled, IC XC, the Greek abbreviation for “Jesus Christ.” The Byzantines viewed the Virgin Mary—Christ’s mother—as a powerful protector. She appears at Christ’s right hand and is labeled, MP ΘY, “Mother of God.” John was a prophet and relative of Christ, whose preaching and baptizing prepared the way for Christ’s ministry in the Gospels. He appears on Christ’s left with the label, “Saint John the Forerunner.”

Deësis mosaic, c. 1261, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the mosaic, Christ sits upon a jeweled throne like an emperor or judge (although most of the throne and bottom half of the mosaic have been lost). The Virgin and John turn inward toward Christ in a three-quarter view, and would have originally extended their hands toward Christ in a pleading gesture. This type of image is referred to as a deësis (δέησις), which means “entreaty,” suggesting an act of asking, pleading, begging. However, this title does not actually appear in the mosaic, and scholars debate whether the Byzantines actually used this term much to describe such images. This type of image reflects the Byzantine belief that the hierarchical order of their empire on earth mirrored heaven above. In the Deësis, the Virgin and John appear like courtiers in the heavenly court, asking God to have mercy on humanity. It is not hard to imagine why such an image of intercession and divine mercy might appeal to the new ruler of an empire still on precarious footing on the world stage.

The Deësis appears in medallions on this fragment of a Byzantine processional cross, c. 1050, silver gilt, niello, 32.3 x 44.8 x 5.7 cm (photo: The Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0) (view annotated image)

The subject of the Deësis is common in art in a variety of media from the Middle Byzantine period onward, often employing a similar composition to that found in Hagia Sophia. But the Deësis was also highly flexible: its figures could be rearranged, replaced by others, or expanded to include additional saints. This is the case with the mid-10th century, ivory Harbaville Triptych, in which Christ, the Virgin, and John—who appear in the top center with angels—are surrounded by a variety of saints.

Harbaville Triptych, mid-10th century, Constantinople, ivory with traces of polychromy, 28.2 x 24.2 x 1.2 cm (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Additionally, the Deësis was often incorporated into larger compositions, such as templon beams and images of the Last Judgment. Scholars have debated possible meanings of the Deësis, sometimes understanding the Virgin and John as witnesses to Christ’s divinity and at other times emphasizing their role as intercessors on behalf of humankind.

Deësis mosaic, c. 1261, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Mosaics and light

The Hagia Sophia Deësis is responsive to the lighting conditions where it is located. Within the image, light appears to shine on the figures from the left, casting shadows to the right. This pictorial light source corresponds with the actual light source of the window on the southern wall beside the mosaic. As a result, light and shadow seem to behave the same within the image and in the physical space the image inhabits, a feature that heightens the naturalism in the mosaic.

This pictorial light source corresponds with the actual light source of the adjacent window (left photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; right photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

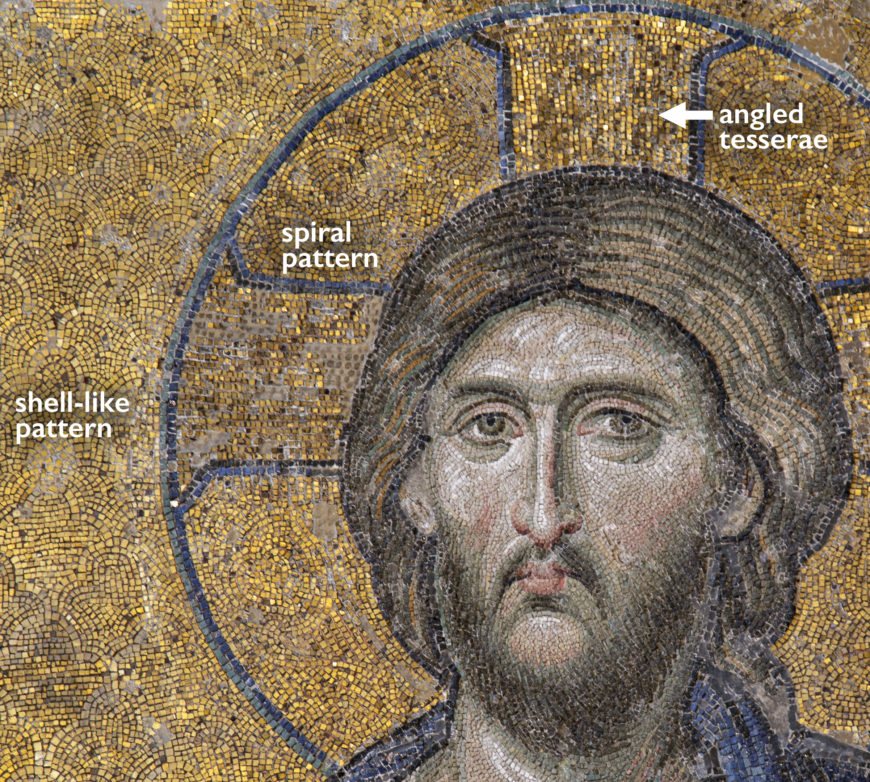

The artists who created this mosaic also considered how individual tesserae would reflect light. The gold tesserae that compose the background are arranged in a shell-like pattern and those in Christ’s halo seem to swirl. The tesserae within the cross in Christ’s halo are angled so they will reflect the light differently from the rest of the gold ground, highlighting the cross.

Deësis mosaic, c. 1261, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Late Byzantine naturalism

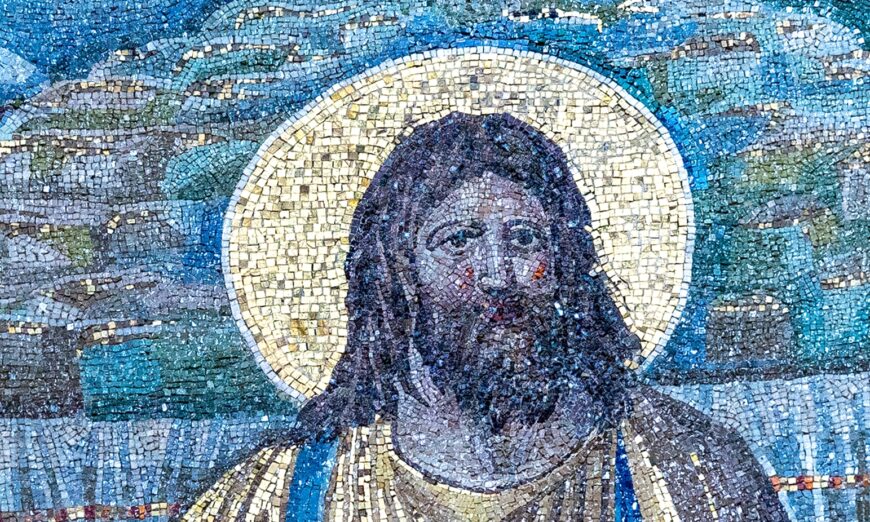

The Deësis at Hagia Sophia illustrates a broader tendency toward naturalism (imitation of the visible world) in Late Byzantine art. Let us compare the image of Christ in the Hagia Sophia Deësis with a Middle Byzantine mosaic of Christ at Hosios Loukas Monastery in Boeotia, Greece, which dates to the eleventh century. The two images both follow the same Byzantine conventions for depicting Christ, who holds a Gospel book in his left hand, blesses the viewer with his right hand, and wears a blue mantle and a tunic with gold highlights in both images. But in the Middle Byzantine mosaic at Hosios Loukas, Christ’s features are simplified. The artist relies heavily on lines to articulate form. As a result, Christ’s body may appear somewhat flat and even cartoon-like to our eyes.

Left: mosaic of Christ, 11th century (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), right: detail of Deësis mosaic, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Certain aspects of the Deësis at Hagia Sophia—such as highlights and drapery folds—are similarly linear. But other elements of the Deësis demonstrate a new tendency toward naturalism. At Hagia Sophia, Christ is more anatomically accurate. The artist has also used modeling—carefully arranging light and dark tesserae—to create a sense of three-dimensional form. And a greater modulation of hues has produced more convincing skin tones.

Dormition fresco, 1260s, church of the Holy Trinity, Sopoćani Monastery, Serbia (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Neither the origins of the artist(s) who created the Deësis mosaic, nor the reasons for the mosaic’s naturalism, are easy to explain. But it should be noted that this tendency toward naturalism is part of a larger trend in Late Byzantine art, which may also be observed, for example, in the wall painting of the Dormition of the Virgin at Sopoćani Monastery in Serbia, also dated to the 1260s.

Left: Detail of Deësis mosaic with the Virgin, c. 1261, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Duccio, Madonna and Child, c. 1290–1300 (photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0)

This attention to naturalism in the Late Byzantine art also corresponds with a similar interest in naturalism among some Italian artists like Duccio, Cimabue, and Giotto who are associated with the beginnings of the Italian Renaissance. Active in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries—not long after the creation of the Deësis in Hagia Sophia—their paintings reveal similar attention to human anatomy and the modeling of form.

Today, the Deësis mosaic in Hagia Sophia still stands as a reminder of the moment when the Byzantines reclaimed their capital from the Latins and when the arts—and an interest in naturalism—flourished.