Made for a member of the Roman elite, this early tomb features Old and New Testament scenes in a classical style.

Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, marble, 359 C.E., almost 8 x 6 x 5 feet (Museum of the Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:06] We’re in the treasury in Saint Peter’s Basilica, in the Vatican in Rome, looking at a large marble sarcophagus. This is the tomb of Junius Bassus.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:15] This sarcophagus is especially interesting because it dates to the mid-4th century, so we’re talking about the very early centuries of Christianity. Christianity has just been made allowable to practice within the Roman Empire by the emperor Constantine.

[0:33] We’re looking at the sarcophagus of a man who lived much of his life as a pagan and then converted to Christianity.

Dr. Zucker: [0:42] This is a transitional moment, when the iconography — that is, the language of representation — is just being developed for Christianity. What’s interesting to me is that there is no image of the crucifixion of Christ here. This is early, and that representational tradition has not yet been developed.

Dr. Harris: [0:59] In fact, Christ appears here enthroned at the top center, surrounded on either side by Peter and Paul, but he looks much more like a youthful Roman emperor than the image of the bearded older Christ as judge that we see later.

Dr. Zucker: [1:14] There are reminders of this earlier pre-Christian polytheistic tradition because Christ’s feet are supported by the Roman god of the sky.

Dr. Harris: [1:23] But clearly in his left hand we see scrolls. We have the idea of Christ as the lawgiver.

Dr. Zucker: [1:29] He and Peter and Paul are so beautifully framed by these Corinthian columns that have shafts that are carved with angelic figures that have a decidedly classical quality to them. It does remind us that the man who commissioned this sarcophagus was wealthy. He was the prefect of the city of Rome.

Dr. Harris: [1:47] Only someone very wealthy could afford such a beautifully carved sarcophagus. We see five scenes on the top, five on the bottom. Each one separated by these lovely columns.

[2:00] All the figures are so deeply carved that they remind me of other figures from the 4th century, like those, for example, that we see on the Arch of Constantine. They look generally classical. They wear togas and ancient Roman clothing, but their heads are a little big and their bodies are a little squat. These are proportions that we see in 4th century ancient Roman art.

Dr. Zucker: [2:24] Nevertheless, these are decidedly Christian images that are drawn from both the Old and the New Testament. Directly below the central scene of Christ enthroned you see an image that is a standard in the Christian story. This is Christ entering the city of Jerusalem.

Dr. Harris: [2:40] This draws on a tradition of Roman emperors entering triumphantly on horseback, but here Christ enters very humbly.

Dr. Zucker: [2:49] Just to the left of that is the oldest scene represented. This shows Adam and Eve, both nude, separated by a tree. If you look carefully, you can see the serpent, that symbol of evil that will tempt Adam and Eve and cause the downfall of mankind, requiring Christ in order to save mankind.

Dr. Harris: [3:07] In fact, we have other scenes here from the Old Testament. We have the scene of Daniel in the lion’s den. This idea that stories from the Old Testament prefigure — that is, they in some ways foreshadow — the events of Christ’s life.

[3:25] We see that especially in the scene at the upper left, where we see the sacrifice of Isaac. Abraham has been asked to sacrifice his only son by God. This scene, for Christians, foreshadows God’s willingness to sacrifice his only son, Jesus Christ, to redeem the sins of mankind.

Dr. Zucker: [3:47] You can see that Abraham once held a knife. The blade has broken off. He holds Isaac by his head. You can see the altar to the lower right and the ram that will ultimately substitute for Isaac to Abraham’s right.

[4:00] Each one of these scenes is beautifully contained within its architectural frame. Let’s spend a moment with the sacrifice of Isaac, and look at the way that Abraham is so beautifully rendered. He stands in a contrapposto. That is, his left leg is bearing the weight of his body, and you can see the right knee breaking through the fabric as he lifts his weight off that leg.

Dr. Harris: [4:21] His face looks so Roman to me. The sculptor uses a small drill to carve the beard, so we have these alternations of light and dark and the sense of these lovely curls in his beard.

Dr. Zucker: [4:33] This is a story about his absolute faith in God and God’s will, and that is so beautifully expressed in that resolute look on his face.

Dr. Harris: [4:42] Here we have a sarcophagus from Junius Bassus, expressing his desire for eternal life in heaven through Christ, only a few centuries after Christ’s death.

[4:55] [music]

Christianity becomes legal

By the middle of the fourth century Christianity had undergone a dramatic transformation. Before Emperor Constantine’s acceptance, Christianity had a marginal status in the Roman world. Attracting converts in the urban populations, Christianity appealed to the faithful’s desires for personal salvation; however, due to Christianity’s monotheism (which prohibited its followers from participating in the public cults), Christians suffered periodic episodes of persecution. By the middle of the fourth century, Christianity under imperial patronage had become a part of the establishment. The elite of Roman society were becoming new converts.

Plaster cast copy of Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, original is 359 C.E., marble (Treasury, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Such an individual was Junius Bassus. He was a member of a senatorial family. His father had held the position of Praetorian prefect, which involved administration of the Western Empire. Junius Bassus held the position of praefectus urbi (“urban prefect”) for Rome, an office established in the early period under the kings, and was responsible for the administration of the city of Rome. It was a position held by members of the most elite families. When Junius Bassus died at the age of 42 in the year 359, a sarcophagus was made for him. As recorded in an inscription on the sarcophagus now in the Vatican collection, Junius Bassus had become a convert to Christianity shortly before his death.

The birth of Christian symbolism in art

The style and iconography of this sarcophagus reflects the transformed status of Christianity. This is most evident in the image at the center of the upper register. Before the time of Constantine, the figure of Christ was rarely directly represented, but here on the Junius Bassus sarcophagus we see Christ prominently represented not in a narrative representation from the New Testament but in a formula derived from Roman Imperial art. The traditio legis (“giving of the law”) was a formula in Roman art to give visual testament to the emperor as the sole source of the law.

Giving of the law (tradition legis) (detail), Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, 359 C.E., marble (Treasury, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Already at this early period, artists had articulated identifiable formulas for representing Saints Peter and Paul. Peter was represented with a bowl haircut and a short cropped beard, while the figure of Paul was represented with a pointed beard and usually a high forehead. In paintings, Peter has white hair and Paul’s hair is black. The early establishment of these formulas was undoubtedly a product of the doctrine of apostolic authority in the early church. Bishops claimed that their authority could be traced back to the original Twelve Apostles.

Peter and Paul held the status as the principal apostles. The Bishops of Rome have understood themselves in a direct succession back to Saint Peter, the founder of the church in Rome and its first bishop. The popularity of the formula of the traditio legis in Christian art in the fourth century was due to the importance of establishing orthodox Christian doctrine.

In contrast to the established formulas for representing Saints Peter and Paul, early Christian art reveals two competing conceptions of Christ. The youthful, beardless Christ, based on representation of Apollo, vied for dominance with the long-haired and bearded Christ, based on representations of Jupiter or Zeus.

The feet of Christ in the Junius Bassus relief rest on the head of a bearded, muscular figure, who holds a billowing veil spread over his head. This is another formula derived from Roman art. A comparable figure appears at the top of the cuirass of the Augustus of Primaporta. The figure can be identified as the figure of Caelus, or the heavens. In the context of the Augustan statue, the figure of Caelus signifies Roman authority and its rule of everything earthly, that is, under the heavens. In the Junius Bassus relief, Caelus’s position under Christ’s feet signifies that Christ is the ruler of heaven.

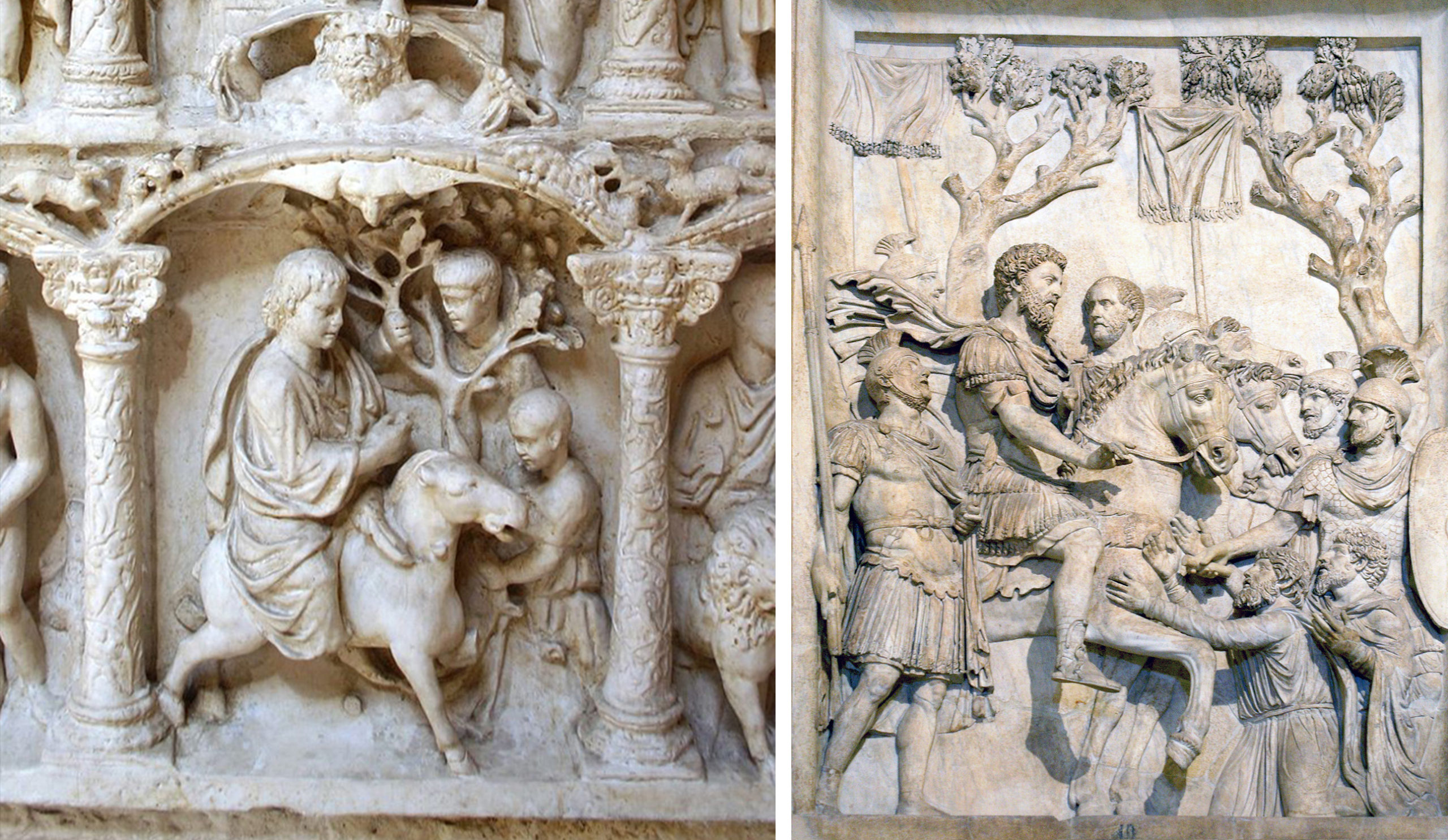

Left: Christ’s entry into Jerusalem (detail), plaster copy of Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, original is 359 C.E., marble (Treasury, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City; photo: Giovanni Dall’Orto); right: Adventus of Marcus Aurelius, 176–80 C.E., marble (Palazzo dei Conservatori, Rome; photo: MatthiasKabel)

The lower register directly underneath depicts Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem. This image was also based on a formula derived from Roman imperial art. The adventus was a formula devised to show the triumphal arrival of the emperor with figures offering homage. A relief from the reign of Marcus Aurelius illustrates this formula. In including the Entry into Jerusalem, the designer of the Junius Bassus sarcophagus did not just use this to represent the New Testament story, but with the adventus iconography, this image signifies Christ’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Whereas the traditio legis above conveys Christ’s heavenly authority, it is likely that the Entry into Jerusalem in the form of the adventus was intended to signify Christ’s earthly authority. The juxtaposition of the Christ in Majesty and the Entry into Jerusalem suggests that the planner of the sarcophagus had an intentional program in mind.

Old and new together

We can determine some intentionality in the inclusion of the Old and New Testament scenes. For example the image of Adam and Eve shown covering their nudity after the Fall was intended to refer to the doctrine of Original Sin that necessitated Christ’s entry into the world to redeem humanity through His death and resurrection. Humanity is thus in need of salvation from this world.

Adam and Eve (detail), plaster copy of Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, original is 359 C.E., marble (Treasury, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The inclusion of the suffering of Job on the left hand side of the lower register conveyed the meaning how even the righteous must suffer the discomforts and pains of this life. Job is saved only by his unbroken faith in God.

The scene of Daniel in the lion’s den to the right of the Entry into Jerusalem had been popular in earlier Christian art as another example of how salvation is achieved through faith in God.

Sacrifice of Isaac (detail), Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, 359 C.E., marble (Treasury, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Salvation is a message in the relief of Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac on the left hand side of the upper register. God challenged Abraham’s faith by commanding Abraham to sacrifice his only son Isaac. At the moment when Abraham is about to carry out the sacrifice his hand is stayed by an angel. Isaac is thus saved. It is likely that the inclusion of this scene in the context of the rest of the sarcophagus had another meaning as well. The story of the father’s sacrifice of his only son was understood to refer to God’s sacrifice of his son, Christ, on the Cross. Early Christian theologians attempting to integrate the Old and New Testaments saw in Old Testament stories prefigurations or precursors of New Testament stories. Throughout Christian art the popularity of Abraham’s Sacrifice of Isaac is explained by its typological reference to the Crucifixion of Christ.

Martyrdom

While not showing directly the Crucifixion of Christ, the inclusion of the Judgment of Pilate in two compartments on the right hand side of the upper register is an early appearance in Christian art of a scene drawn from Christ’s Passion. The scene is based on the formula in Roman art of Justitia, illustrated here by a panel made for Marcus Aurelius. Here the emperor is shown seated on the sella curulis dispensing justice to a barbarian figure. On the sarcophagus, Pilate is shown seated also on a sella curulis. The position of Pontius Pilate as the Roman prefect or governor of Judaea undoubtedly carried special meaning for Junius Bassus in his role as praefectus urbi in Rome. Junius Bassus as a senior magistrate would also be entitled to sit on a sella curulis.

Judgement of Pilate (detail), Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, 359 C.E., marble (Treasury, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Just as Christ was judged by Roman authority, Saints Peter and Paul were martyred under Roman rule. The remaining two scenes on the sarcophagus represent Saints Peter and Paul being led to their martyrdoms. Peter and Paul as the principal apostles of Christ are again given prominence. Their martyrdoms witness Christ’s own death. The artists seem to be making this point by the visual pairing of the scene of Saint Peter being led to his martyrdom and the figure of Christ before Pilate. In both scenes the principal figure is flanked by two other figures.

The importance of Peter and Paul in Rome is made apparent in that two of the major churches that Constantine constructed in Rome were the Church of Saint Peter and the Church of Saint Paul Outside the Walls. The site of the Church of Saint Peter has long believed to be the place of Saint Peter’s burial. The basilica was constructed in an ancient cemetery. Although we can not be certain the the Junius Bassus Sarcophagus was originally intended for this site, it would make sense that a prominent Roman Christian like Junius Bassus would want to be buried in close physical proximity to the burial spot of the founder of the Church of Rome.

Competing styles

At either end of the Junius Bassus sarcophagus appear Erotes harvesting grapes and wheat. A panel with the same subject was probably a part of a pagan sarcophagus made for a child. This iconography is based on images of the seasons in Roman art. Again, the artists have taken conventions from Greek and Roman art and converted it into a Christian context. The wheat and grapes of the classical motif would be understood in the Christian context as a reference to the bread and wine of the Eucharist.

Erotes harvesting grapes (detail), plaster copy of Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, original is 359 C.E., marble (Treasury, St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City; photo: Giovanni Dall’Orto)

Erotes harvesting grapes (detail), Sarcophagus representing a Dionysiac Vintage Festival, 290–300 C.E., marble (Getty, Los Angeles)

While the proportions are far from the standards of classical art, the style of the relief, especially with the rich folds of drapery and soft facial features, can be seen as classic or alluding to the classical style. Comparably the division of the relief into different registers and further subdivided by an architectural framework alludes to the orderly disposition of classical art. This choice of a style that alludes to classical art was undoubtedly intentional. The art of the period is marked by a number of competing styles. Just as rhetoricians were taught at this period to adjust their oratorical style to the intended audience, the choice of the classical style was seen as an indication of the high social status of the patron, Junius Bassus. In a similar way, the representation of the figures in togas was intentional. In Roman art, the toga was traditionally used as a symbol of high social status.

In both its style and iconography, the Junius Bassus Sarcophagus witnesses the adoption of the tradition of Greek and Roman art by Christian artists. Works like this were appealing to patrons like Junius Bassus who were a part of the upper level of Roman society. Christian art did not reject the classical tradition: rather, the classical tradition will be a reoccurring element in Christian art throughout the Middle Ages.