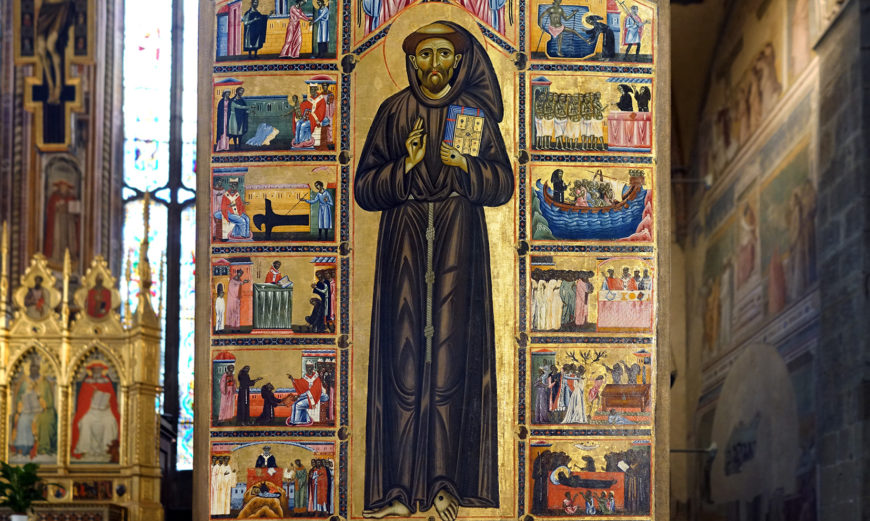

A frame of narrative scenes depict the biography of Saint George in this Byzantine icon.

Vita Icon of Saint George with Scenes of His Passion and Miracles, early 13th century, tempera and gold on wood, 127 x 80 x 3.5 cm (The Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai). Speakers: Dr. Evan Freeman, Hellenic Canadian Congress of BC Chair in Hellenic Studies at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Centre for Hellenic Studies at Simon Fraser University and Dr. Beth Harris