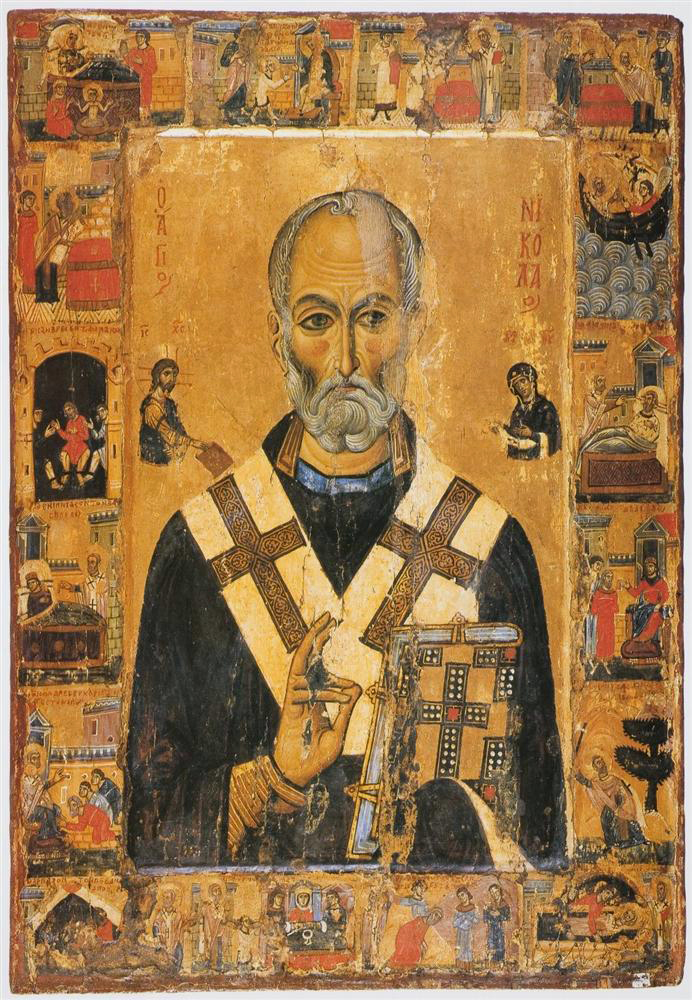

Vita icon of St. Nicholas, late 12th to early 13th century (Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, Egypt)

The “vita” icon is literally the image of a life. Its usual format consists of the magnified central portrait of a saint surrounded by those episodes in his/her biography that made him/her a saint. In these vignettes, the saint appears in a smaller and relatively more active stance as s/he goes about the business of sanctity by performing miracles, praying, and sometimes, even being martyred.

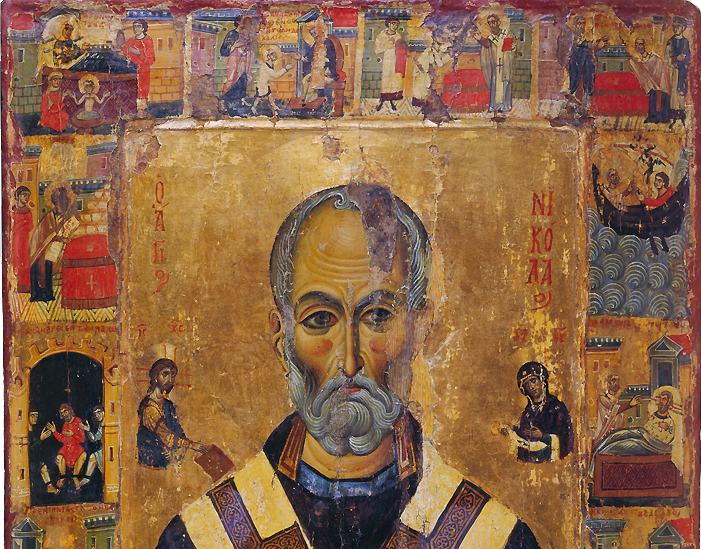

Detail, Vita Icon of St. Nicholas (detail), late 12th to early 13th century (Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, Egypt)

A vita icon of St. Nicholas

The “vita” icon of St. Nicholas, currently located in the Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, Egypt, is a perfect example. The bust of the saint looms large at the center whereas the smaller, full-figured, mobile version of Nicholas features on, and as, a frame on all four sides.

St. Nicholas as an infant in the bath, detail from icon of St. Nicholas, late 12th to early 13th century, Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, Egypt (Princeton University)

One may begin to read this frame from the top left hand corner (although we have no evidence that viewers did so) where Nicholas appears as an infant who miraculously stood erect in his bath. As we proceed horizontally, we see Nicholas’ transformation to a child, an adolescent, and finally, at the top right hand corner, an adult.

St. Nicholas as an infant, child, adolescent, and adult, details from icon of St. Nicholas, late 12th to early 13th century, Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, Egypt (Princeton University)

But after that, one might be at a loss as to know where to direct one’s gaze, for nowhere are we given any specific visual or textual directions (although in some examples of the “vita” icon, one may detect, upon trying, a logical narrative design to the episodes). We could skip to the left-hand side of the panel and continue vertically all the way down, or we could scan the rectangular panels on the left and right alternately, criss-crossing the still, hieratic, central bust as we do so. Regardless of the visual path we choose to follow, we catch glimpses of various moments in Nicholas’ life.

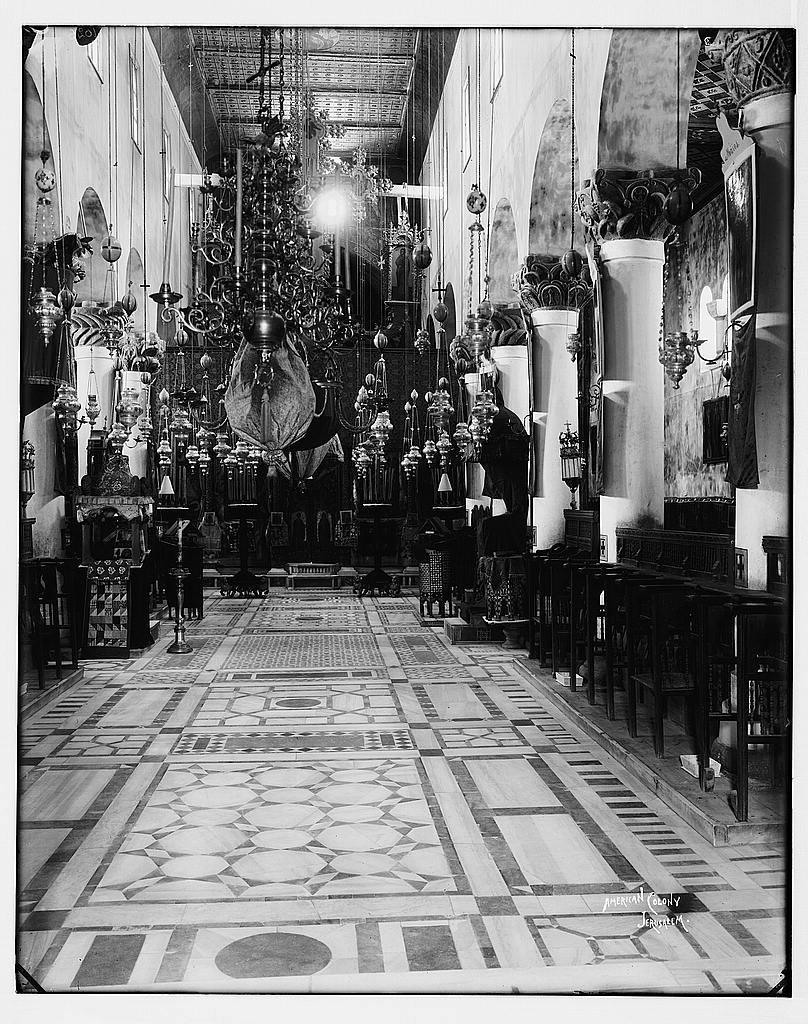

Inside the basilica at Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai (photo: Library of Congress)

Viewers may even have focused on a small selection of scenes, or the bust alone, depending on lighting conditions and how close they might have been to the icon. In the flicker of candle light, it is more than probable that a number of details on the frames might have been lost. However, if the “vita” icon were displayed as a proskynetarion icon (an image placed on a stand, usually at eye level, for veneration on a feast day), then it probably would have been visible for contemplation in its entirety at various moments of the day. This example of the icon of St. Nicholas suggests a flexibility of viewership enabled by the “vita” format in juxtaposing the monumental and miniature versions of a saint in a non-linear orientation.

Origins of the vita icon

The precise date of the origin of the “vita” icon format is debated, with some arguing for the 10th century C.E. and others positing a slightly or much later period ranging from the 11th to the 13th centuries. The general characteristics of the format in the Byzantine Empire are: size (ranging from 70 cm to 2 m in height), and the remarkable consistency of standardized scenes that appear on the frame from icon to icon; in other words, surviving “vita” icons of St. Nicholas often display similar scenes. The frame is an intriguing phenomenon in itself since from the 11th-century onward we find the addition of precious revetments (thin sheets) of gold, silver, and other metals, which often feature donor portraits and inscriptions.

Metal revetment appears on the frame and around the central figure on this icon of St. Theodore the Stratelates, mid-16th century, from the church of St. Theodore the Stratelates on the Brook (Novgorod Integrated Museum-Reservation, Novgorod, Russia) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Image and text

“Vita” icons usually incorporate texts identifying the saint and the episodes from his/her life. While we might expect the narrative scenes in the frames of “vita” icons to parallel written accounts of saints’ lives, or “hagiographies,” which were widely circulated in the medieval era, scholars have remarked on the apparent independence of “vita” icons from the standard textual versions of the lives of the saints depicted. By the 11th century in the Byzantine Empire, saints’ lives had been compiled into a more or less definitive version by Symeon Metaphrastes known as the Metaphrastean Menologion; yet, the “vita” icons from the 13th century do not reflect this book so much as older hagiographies. Some have argued that this was probably because the 13th-century exemplars are copies of even older “vita” icons which, in turn, relied on the earlier hagiographical texts. While this may have been the case from the point of view of the creators and patrons of the icons, from the perspective of the viewer these panels may be read as visual statements in their own right with the inscriptions permitting the identification of scenes, not necessarily intended to evoke specific passages in written hagiographies.

The mobility of vita icons

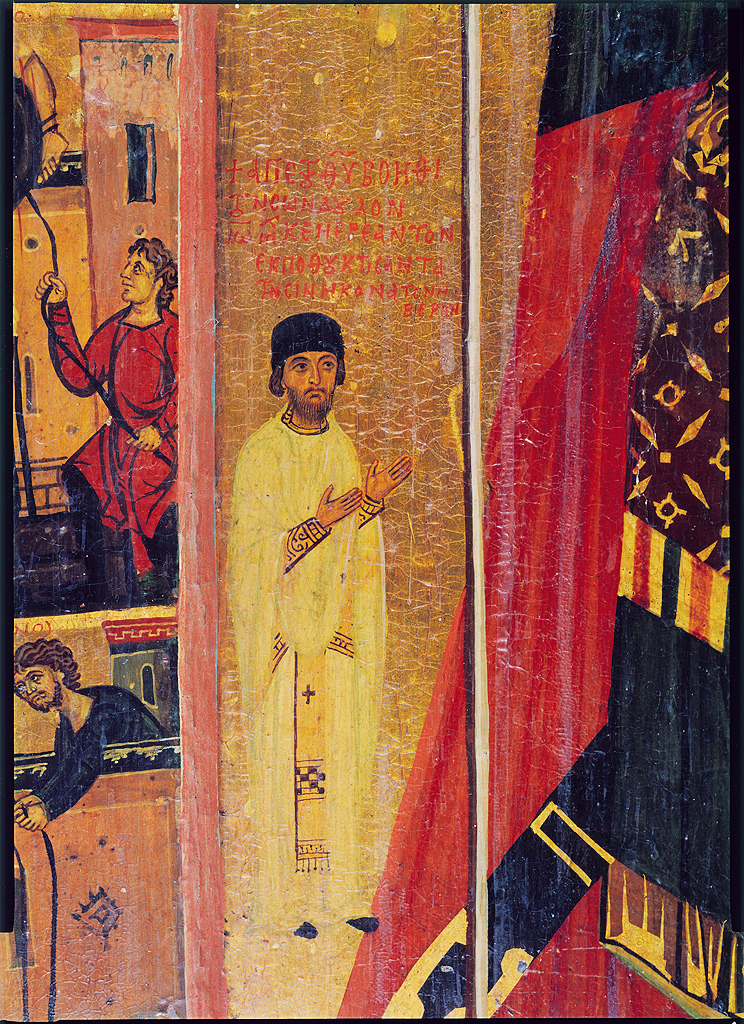

Donor figure identified as “John the Iberian,” vita icon of St. George, late 12th or early 13th century, Monastery of St. Catherine, Sinai, Egypt (Princeton University)

Since a significant number of Byzantine “vita” icons are preserved in the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai, Egypt (view location on map), it is possible that some might have been gifted or donated to the Monastery by pilgrims. One of the 13th-century “vita” icons of St. George, for example, depicts a donor figure sandwiched between the towering, imposing figure of the warrior-saint and the frame. Clad in white in stark contrast to the broad swathes of red and black characterizing George, this figure is identified as John the Iberian (“Iberian” here is a reference to medieval Georgia on the eastern shore of the Black Sea) who was both monk and priest. Alternatively, some of the icons might have been made at the Monastery of St. Catherine itself.

More interesting than these questions of origins, is the fact that the “vita” icon format gained popularity across Europe within a relatively short period. This may have occurred because of its distinctiveness and clarity in conveying information about saints as individuals, as well as its ability to make a vivid visual statement about sanctity writ large. Examples are known in Italy, Cyprus, and Russia, among other places.

Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Saint Francis Altarpiece, c. 1235, tempera on wood, 5′ high (San Francesco, Pescia, Italy)

Vita icons, east and west

“Vita” icons were most strikingly used in the service of one of the most radical saintly personalities of the medieval west: Francis of Assisi, whose life and many posthumous miracles were included in the format. As the first person to have been recognized officially as a genuine stigmatic (St. Francis was blessed with the wounds of Christ) by the Catholic Church, St. Francis revolutionized ideas of the human body (as an image of the divine), the natural world (Francis preached to birds and other animals), and property (Francis advocated the renunciation of worldly possessions), although a number of Franciscan ideals stemmed from existing strands of ascetic and monastic thought and practice.

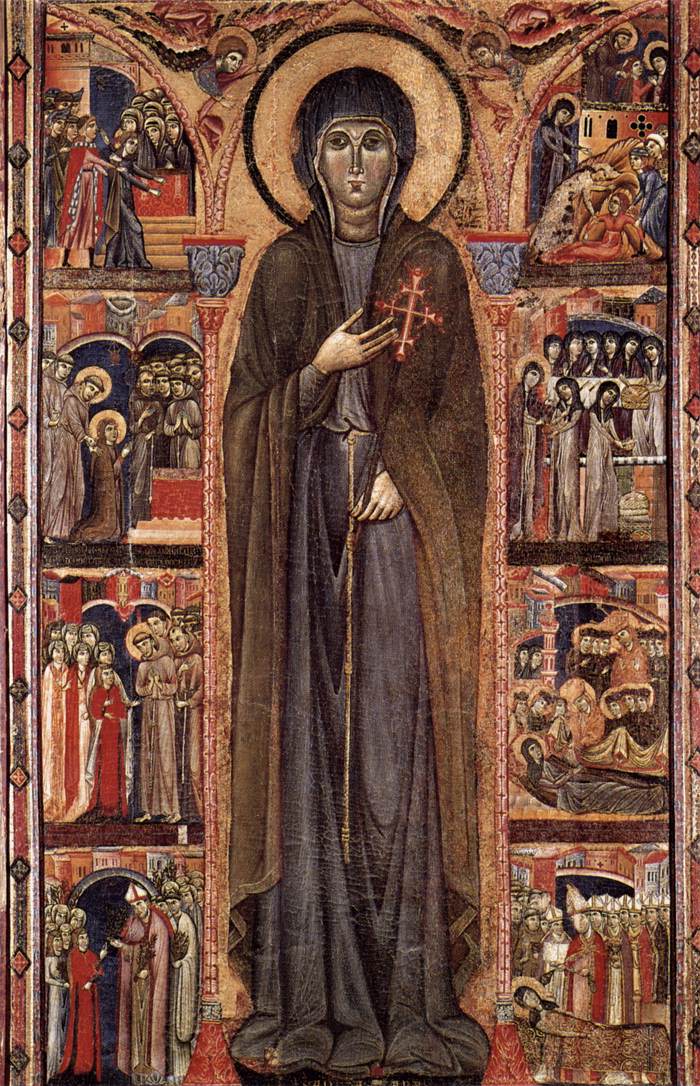

Vita icon of St. Clare (Santa Chiara Dossal), 1280s (Wikimedia Commons)

One major difference between the Byzantine and Western “vita” icons is that the format was almost exclusively used in the east for well-established, long-deceased saints (e.g. Nicholas and George) and in the west for recently minted saints (e.g. Francis), and initially for those associated with the Franciscan Order such as St. Clare of Assisi and St. Margaret of Cortona.

Master of the Bardi Saint Francis, Altarpiece with scenes from the life of Saint Francis of Assisi (Bardi Dossal), c. mid 13th century, tempera on panel, Bardi Chapel, Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Some of the Franciscan “vita” icons were also used as altarpieces (a work of art set above and behind an altar)—a category of object that was never used in the medieval Orthodox church, but which furnished a focus of devotion and a high degree of visual elaboration in the Roman Catholic churches of western Europe.

Left to right: Sts. Boris and Gleb with scenes of their lives, second half of the 14th century, Moscow (Tretyakov Gallery); Elijah the Prophet in the wilderness with scenes of his life and Deësis, second half of the 13th century, Pskov (Tretyakov Gallery); St. Nicholas (St. Nicholas of Zaraisk) with scenes of his life, second half of the 14th century, Rostov (Tretyakov Gallery)

In Slavic Russia, too, by the fourteenth century we find the phenomenon of recent saints such as Boris and Gleb, sons of prince Vladimir the Great of Kievan Rus’, portrayed in the “vita” format, along with icons dedicated to far more traditional figures such as Elijah and St. Nicholas.

Detail of St. Nicholas (St. Nicholas of Zaraisk) with scenes of his life, second half of the 14th century, Rostov (Tretyakov Gallery) (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

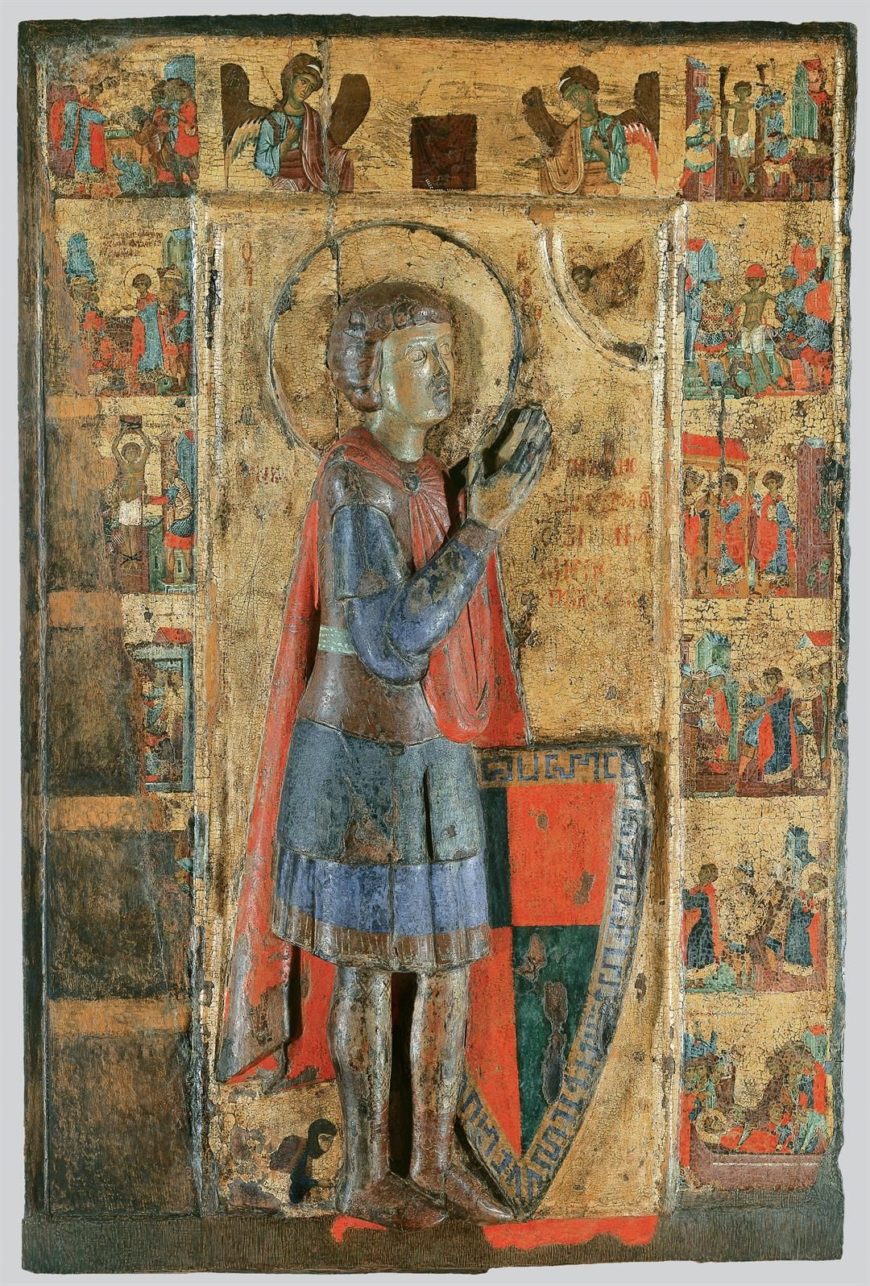

Relief icon with St. George and St. Μarina and Irene (?) on back, 13th century, 107 x 72 cm (photo © Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens)

Variations

Although “vita” icons most commonly appear in tempera on wood panels, we sometimes find the “vita” format deployed in intriguing variations in media, such as in frescoes or textiles. In some instances, the confection plays on the deliberate contrast of media, displaying the central figure in relief and the images on the frame as panel paintings, as seen with a thirteenth-century icon of St. George in Athens.

Left: St. Nicholas fresco, 12th century, church of St. Nicholas tis Stegis, Kakopetria, Cyprus (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); Right: vita icon with St. Nicholas, late 13th century, 203 x 158 cm, from the church of St. Nicholas tis Stegis, Kakopetria, Cyprus (Archbishop Makarios III Foundation, Byzantine Museum)

Church of St. Nicholas tis Stegis, Kakopetria, Cyprus (photo: byzantologist, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In other cases the “vita” format seeks to recreate not just the saint per se, but a specific local image of the saint which was probably known and venerated previously. Such is the case of the church of St. Nicholas tis Steges in Kakopetria, Cyprus in which a life-sized frescoed image of St. Nicholas was likely reproduced in the large “vita” icon dedicated to the same saint and formerly located in that very church. Interestingly, this vita icon of St. Nicholas portrays Latin, and not Byzantine, donors on its frame, thus attesting to the general appeal of the visual format across faiths and ethnicities.