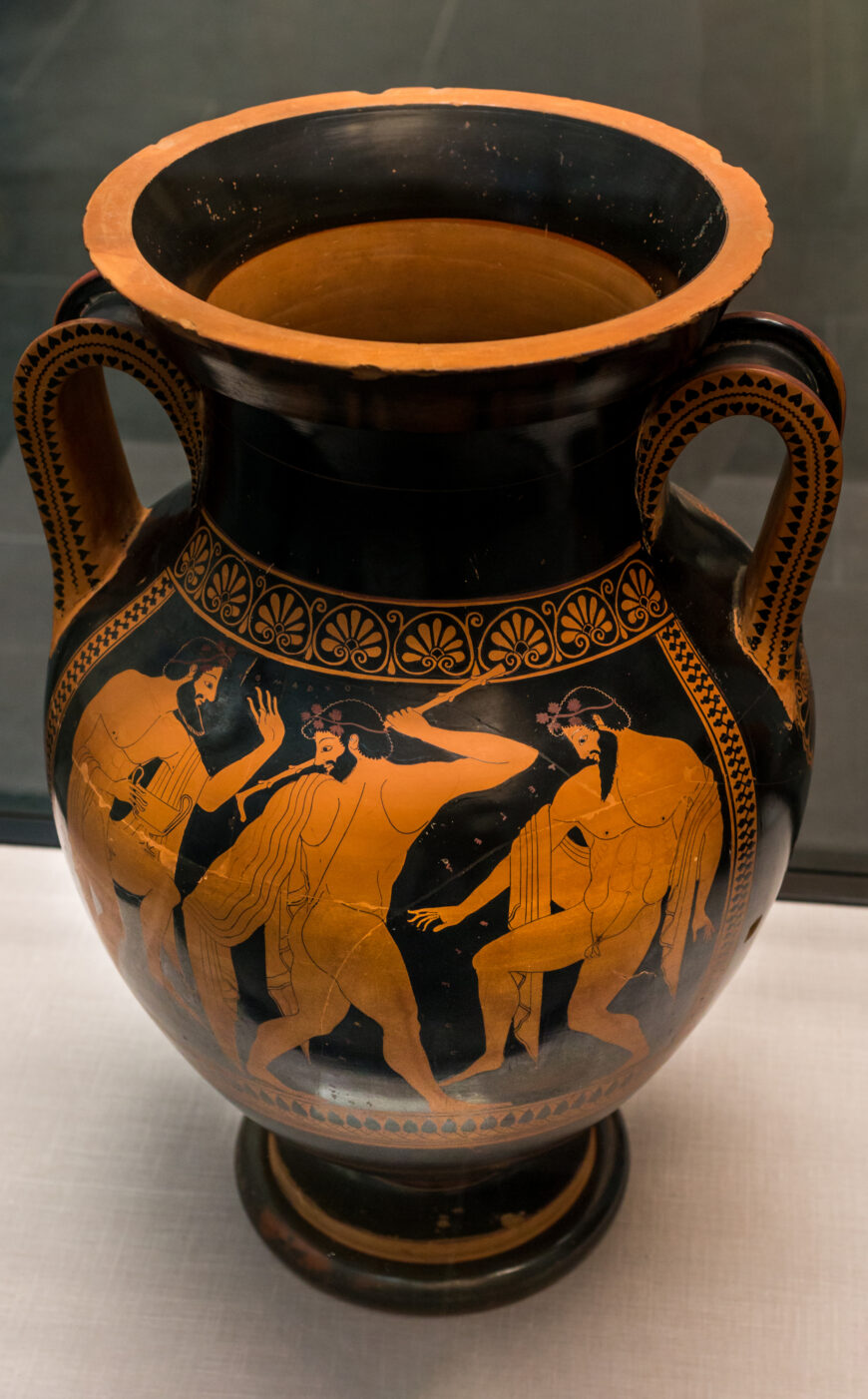

Euthymides, Three Revelers (Athenian red-figure amphora), c. 510 B.C.E., 61 cm high (Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Competition

“As never Ephronios [could do]” wrote painter Euthymides after painting his new amphora. Euthymides had a clear sense of achievement and was indeed proud of his work, boastfully challenging his friend and rival—Euphronios. He would see Euphronios often, as well as other painters in the Kerameikos—the potter’s quarter in Athens. They would be curious to see one another’s new work, sometimes with appreciation, sometimes with a bit of jealousy. In the evenings they often had a good time together at a symposium (a kind of ancient Greek male drinking party). They would drink wine mixed with water, become garrulous, loud and—if drinking went on for too long—they might even start singing and even dancing. Perhaps what is depicted on this amphora is a scene similar to those Euthymides witnessed at one of these long parties. Euphronios indeed was a master potter and painter, and Euthymides knew that and had a full appreciation for his work. He thought however, that his figures seemed much more lively, caught in a split of a moment, in a dancing movement.

Detail, Euthymides, Three Revelers (Athenian red-figure amphora), c. 510 B.C.E., 61 cm high (Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The beginnings of red-figure painting

Euthymides worked mainly between 515 and 500 B.C.E., in a time when artists were exploring the possibilities of red-figure technique, invented in Athens around 530 B.C.E. Both Euthymides and Euphronios belonged to a kind of camaraderie of artists, often dubbed the “Pioneer Group” by art historians—referring to their innovative efforts in the new technique. In the red-figure technique, an artist sketches figures on the red clay of a freshly fashioned vessel, then covers all the background with a slip (a liquid clay), which turns black after final firing. Details, like elements of anatomy, folds of drapery, etc., can be freely added with a thin brush; the slip can be darker, sometimes more diluted, brownish, adding even more variety. In the black-figure technique which was used previously, an artist had to fill the figures with slip, and then incise the details with a sharp burin (a lozenge-shaped tip) which was much more difficult to handle. At the time of the “Pioneers,” there is a general trend in Greek art to observe the reality and represent human body more realistically, leaving the more stiff archaic models behind.

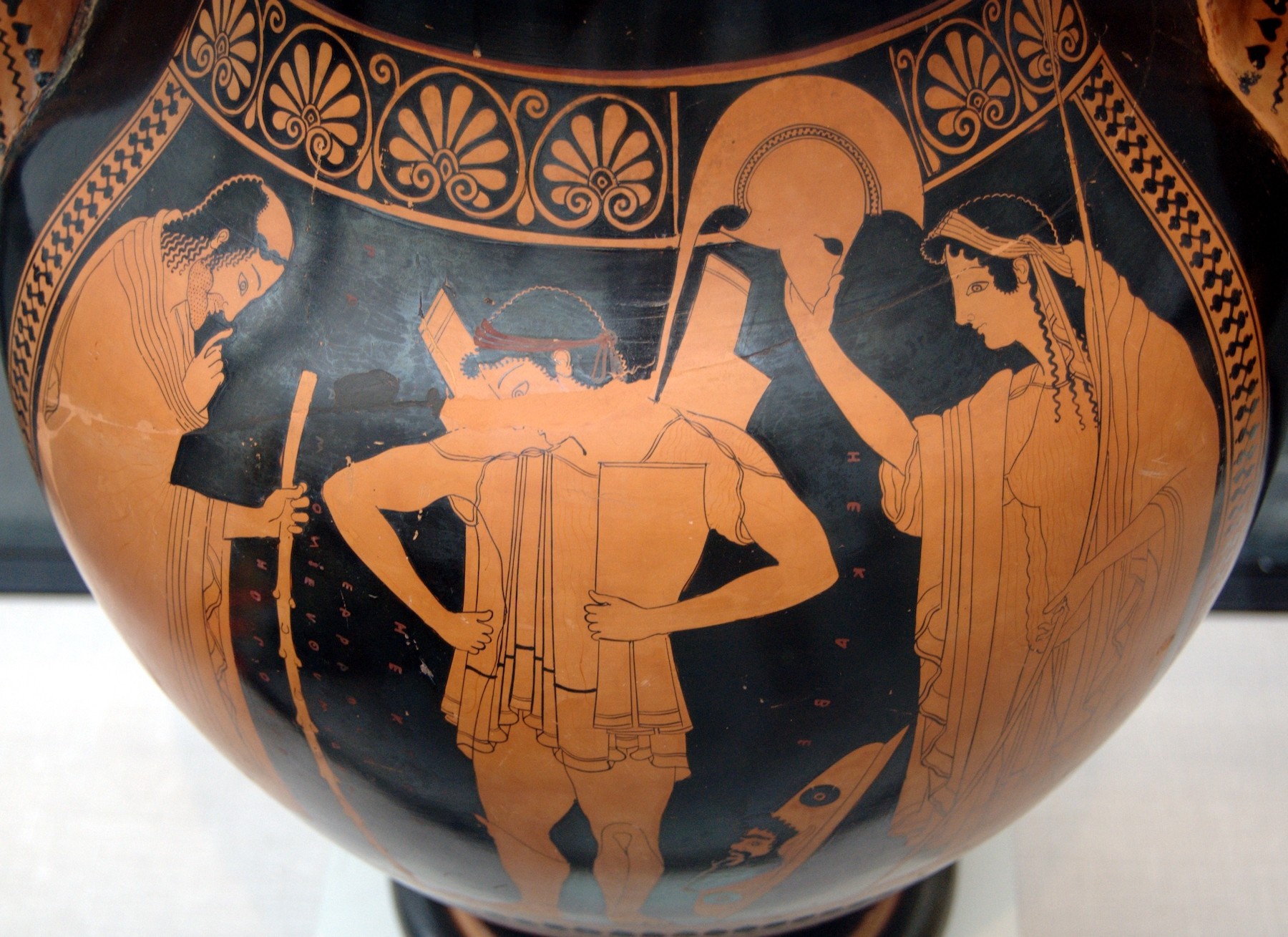

Hector receiving the helmet from Hecube (detail), Euthymides, Three Revelers (Athenian red-figure amphora), c. 510 B.C.E., 61 cm high (Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Hector departs for war

Drinking and dancing with kantharos (detail), Euthymides, Three Revelers (Athenian red-figure amphora), c. 510 B.C.E., 61 cm high (Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Coming back again to the “Three Revelers” vase—on one side of his amphora the artist decided to decorate with a mythological scene—a solemn moment of Hector departing for the Trojan War, receiving the helmet from his mother Hecube.

On the other side of the vase, which is probably better known, the artist gave way to his keen sense of observation, giving us a glimpse into everyday life. Three rather tipsy men dance around, enjoying their moment during a long symposium. The one on the left still keeps in his hand a kantharos—a wine cup with long handles. Euthymides made an effort to show them neither completely frontally, nor completely in profile, but rather in three quarters view, using foreshortening to convey a vivid, realistic image. The poses are very diversified, the man in the center is represented in a twisted view. The artist brought his keen sense of observation to describing human anatomy and movement. Greek vase painters often give us clear insight into everyday life—allowing us to understand daily habits, details of clothing and customs. Of course, these painted vases cannot be treated as documents, since we would not expect men to be naked at a symposium. However, appreciation for the human body and nudity was a usual part of ancient Greek culture, and it provided a way for the artist to showcase his ability.

Drinking and dancing with kantharos (detail), Euthymides, Three Revelers (Athenian red-figure amphora), c. 510 B.C.E., 61 cm high (Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Euthymides, Three Revelers (Athenian red-figure amphora), c. 510 B.C.E., 61 cm high (Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich; photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The vase displays balance and harmony of proportions, with its elegant and graceful shape, and carefully planned pictorial decoration. The main scenes on both sides of the amphora are complemented by a delicate ornament. Despite the beauty of the vase, the potters and painters in ancient Greece did not have the status an artist has in our modern society. Their work was looked upon as a physical labor, not as an activity inspired by the muses. In fact, there was no muse of painting. The decorated vases were produced in large amounts to answer the growing demand of the markets, both in Greece, as well as abroad (especially in Etruria, and in Greek colonies). The Euthymides vase was in fact found in an Etruscan tomb at Vulci in Italy. Many Greek vases survived untouched because the Etruscans buried their deceased in large underground tombs with many everyday objects.

Most of the vases were simply everyday items, although a big, beautifully painted amphora like the one discussed here was also a luxury item, testifying to its owner’s good taste and social standing. Despite their status as craftsmen, the artists around the time of Euthymides had a sense of personal value and achievement, hence the inscription “As never Euphronious [could do]”. Because of the inscription “Euthymides egraphsen” (“Euthymides painted me”) we are sure that he was the painter—and today we definitely think of him as an artist.

Additional resources

Learn more in a Reframing Art History chapter about “Pottery, the body, and the gods in ancient Greece, c. 800–490 B.C.E.”

Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques.

This Amphora in the Beazley Archive.

J. Boardman, Athenian Red Figure Vases, The Archaic Period, a Handbook (1975).