If the Roman government condemned a ruler, his portraits often died with him.

Detail of Geta (face removed) and Caracalla from the Severan Tondo, c. 200 C.E., tempera on wood, 30.5 cm diameter (Altes Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

We know that Roman emperors were often raised to the status of gods after their deaths. However, just as many were given the opposite treatment—officially erased from memory.

Condemning memory

Damnatio memoriae is a term we use to describe a Roman phenomenon in which the government condemned the memory of a person who was seen as a tyrant, traitor, or other sort of enemy to the state. The images of such condemned figures would be destroyed, their names erased from inscriptions, and if the doomed person were an emperor or other government official, even his laws could be rescinded. Coins bearing the image of an emperor who had his memory damned would be recalled or cancelled. In some cases, the residence of the condemned could be razed or otherwise destroyed. [1]

This was more than a form of casual, politically-motivated vandalism, carried out by disgruntled individuals, since the condemnation required approval of the Senate and the effects of the official denunciation could be seen far from Rome. There are many examples of damnatio memoriae throughout the history of the Roman Republic and Empire. As many as 26 emperors through the reign of Constantine had their memories condemned; conversely, about 25 emperors were deified after their deaths. The damning of memory phenomenon, however, is not unique to the Roman world. Egyptian pharaohs Hatshepsut and Akhenaten likewise had many of their their images, monuments, and inscriptions destroyed by political opponents or religious purists. [2]

Did it work?

Portrait of Emperor Caligula, 37-41 C.E., marble, 28 cm high (Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, photo: Dr. Francesca Tronchin, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Instances of damnatio memoriae were not always completely successful in wiping out the memory of an individual. Among the emperors who suffered damnatio memoriae are some of the best-known figures from Roman history, including Gaius (a.k.a. Caligula) and Nero. The notoriety of these men comes to us not only from texts written during their lifetimes and later, but also from images which survived the immediate violence of the damnatio memoriae and then centuries of neglect.

For instance, one marble portrait preserves not only the image of Caligula, but also traces of paint, informing us of the existence of this condemned emperor as well as the polychromy of ancient sculpture. In antiquity, these types of images were considered very powerful and closely linked with the identity of the person they represented.

Two portrait heads of Emperor Caligula, created 37-41 C.E., marble, both detached from the sculpted bodies after his death. Left: 43 x 21.5 x 25 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles); right: 33 x 21 x 23.5 cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

Portrait statue of Caligula, recarved as Claudius, from the Basilica at Velleia, first half of the 1st century C.E., marble, 221 cm high (Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Parma, photo: Sailko, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Small heads, big reputations

Caligula was the first emperor to have his images purposefully destroyed after his death. It is impossible to know how many portraits in bronze or other precious metals were melted down, but a number of marble portraits show traces of being re-cut or simply dismantled and disposed of. Workshop procedures for official imperial portraits dictated that many full-length statues in stone were to be created in two pieces. So heads of Caligula, like those now in the Getty Villa and the Yale University Art Gallery (above), could be fairly easily detached from the bodies and tossed aside and a portrait head of the new emperor would swiftly replace the offending one.

A full-length, one-piece statue of a pontifex maximus (chief state priest, a title held by the emperor) from Velleia, however, apparently underwent a kind of sculptural recycling. The face of Caligula’s successor Claudius appears rather small in comparison to the head and the rest of the body—suggesting to some scholars that it was cut down from a portrait of Caligula.

Cancelleria Reliefs: Nerva replaces Domitian

Domitian recut into Nerva, detail of a felief from the Palazzo della Cancelleria, 81-96 C.E., marble (Museo Gregoriano Profano, Vatican Museums, photo: Erin Taylor, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

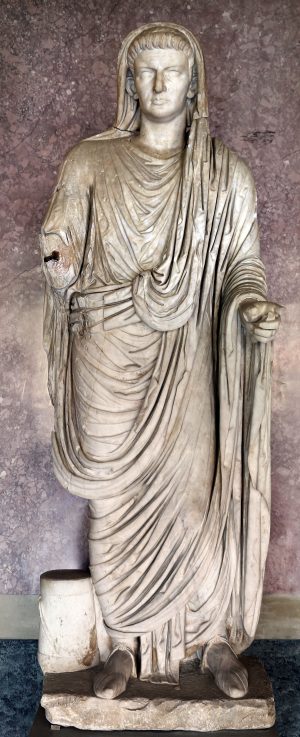

A similar re-cutting is evident on a set of reliefs found in Rome and now housed in the Vatican Museums (below). The so-called Cancelleria Reliefs show mythological and allegorical figures celebrating members of the Flavian dynasty for their military successes.

In one, Domitian departs from Rome on a military campaign, ushered out of the city by Victoria, Mars, and Minerva, as well as personifications of the Senate and the Roman people. Yet the head atop the stately tunic-clad body of the emperor is not that of Domitian. Instead it is Nerva, who succeeded Domitian after his assassination and subsequent damnatio memoriae. As in the Claudius pontifex maximus statue from Velleia, Nerva’s face is far too small for the relief and even appears comical when compared to the divinities surrounding him.[3] Apparently the sculpture was recarved.

Relief from the Palazzo della Cancelleria, 81-96 C.E., marble (Museo Gregoriano Profano, Vatican Museums, photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Domitian/Nerva can be seen fourth from the left.

Slightly more elegant solutions for damnatio memoriae could be executed in metal statuary. The face of a bronze equestrian portrait of Domitian (below) was sawed off and replaced with that of his successor, Nerva. The result is much less jarring than on the Cancelleria relief, as the bronze “mask” was made to the same scale as the rest of the statue and the join is mostly unnoticeable.

Equestrian statue of Nerva (formerly Domitian), from the Sanctuary of Augustales, Miseno, bronze (Museo Arceologico dei Campi Flegrei, Bacoli, photo: Erin Taylor, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Caracalla removes the image of Geta

Relief showing Septimius Severus and Julia Domna with a caduceus, Arch of the Argentarii, Rome, completed 204 C.E. (photo: Panairjdde, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Perhaps the most striking and widespread examples of damnatio memoriae come from the reign of Caracalla, a member of the Severan Dynasty who ruled from 211-217 C.E. He was initially co-emperor with his younger brother Geta, but after months of squabbling between the sibling rulers, Caracalla had Geta assassinated. This death was quickly followed by a damnatio memoriae, one in which it became a capital offense to even speak the name of the younger co-emperor.

In Rome, Geta’s image was eliminated from reliefs on the Arch of the Argentarii. No attempt at an elegant recarving was made as in the Cancelleria Reliefs; in a panel showing Septimius Severus and Julia Domna (the parents of Caracalla and Geta) sacrificing at an altar, a caduceus floats over an empty space where Geta must have stood.[4] Even images of Geta’s wife and father-in-law were carved out of the Arch of the Argentarii panels, as they too had suffered a damnatio memoriae. The names of all the condemned individuals were erased from the arch and replaced with new inscriptions honoring Caracalla.

Severan Tondo, c. 200 C.E., tempera on wood, 30.5 cm diameter (Altes Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0). This circular painting is exceptional for its materials, state of preservation, and insight into Roman painting beyond frescoes and other murals.

Erasing memory across time and space

A painted panel found in Egypt demonstrates the very long reach of Roman vengeance when enacting a damnatio memoriae. The panel shows the Severan family: Julia Domna wears heavy pearl earrings and necklaces; Septimius’s hair and beard are tinged with gray; and highlights in the eyes of all the figures add a lifelike quality. Caracalla’s boyish face—painted when he was merely heir to the throne—peers out to the viewer’s left. Next to him is a circular erasure in the paint where Geta once appeared. This deletion is dramatic when considering the procedures of damnatio memoriae. Someone in the province of Egypt, far from the center of the Empire, was charged with erasing the image of a child—a child who grew up to be co-emperor, only to be killed by his own brother. The tyranny of Caracalla and the thoroughness of damnatio memoriae meant that practically no image of the emperor’s enemies, no matter how small or out-of-date, would escape destruction.

Damnatio memoriae continued in the Roman world through the fourth century C.E., as seen in disfigured portraits of Constantine’s rival Maxentius. With Christianity made official in the Roman world, vandalism of imperial portraits continued, but with more of a religious bent than a political one. The fact that Roman portraits were removed, damaged, or destroyed because of dramatic changes in the subjects’ reputations is unmistakable evidence that such images are more than just “pictures.” A portrait can carry meaning over decades and centuries—whether it is of a Roman emperor, a Communist leader like Joseph Stalin, a dictator like Saddam Hussein, or Confederate generals in the United States.

Notes:

- Nero’s Domus Aurea (Golden House) in downtown Rome was eventually filled in and built over by his successors in the Flavian Dynasty, but it was not a systematic destruction. In fact, there is evidence Vespasian lived in the controversial villa before he and his sons turned the land from Nero’s private estate back over to the public.

- Hatshepsut’s successor, Thutmose III, ordered her images, cartouches, and monuments destroyed as she was seen as a usurper to his throne. Akhenaten, who brought monotheism briefly to Egypt, suffered a sort of damnatio memoriae by those who enthusiastically returned to polytheism after his death.

- In a coup de grâce for the Cancelleria Reliefs, they seem to have never been displayed, instead discarded in a Republican-period cemetery after Nerva died just fifteen months into his reign. The Flavian Dynasty was over and it would have been too challenging to re-recarve the portrait of Nerva into Trajan.

- It appears that Julia Domna’s left arm was carved in the space where Geta’s body once was; in the original format, she was probably holding the caduceus.

Additional Resources:

Sarah Bond, “Erasing the Face of History,” The New York Times, May 14, 2011

S. Bundrick and E. Varner, From Caligula to Constantine: Tyranny & Transformation in Roman Portraiture (Michael C. Carlos Museum, 2001).

Harriet I. Flower, The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace & Oblivion in Roman Political Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

Eric Varner, Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture (E.J. Brill, 2004).