Scene of an imperial lion hunt, front panel of the Troyes Casket, Middle Byzantine, Constantinople (?), ivory and purple pigment, 13 x 26 x 13 cm, Cathedral Treasury, Troyes France.

Scenes of an imperial lion hunt (front panel), imperial procession (lid panel), and feng huang bird (end panel) of the Troyes Casket, Middle Byzantine, Constantinople (?), ivory and purple pigment, 13 x 26 x 13 cm, Cathedral Treasury, Troyes France.

The treasury of the cathedral of Troyes (France) houses an unexpected masterpiece of Middle Byzantine secular art. This ivory casket combines conventional images of imperial might—the top, front, and back of the casket depict emperors departing on campaign and engaged in heroic hunts against a lion and wild boar—with a most un-Byzantine decorative motif on the short end panels, which depict the mythical Chinese bird known as the feng huang (commonly referred to as a phoenix). The ivory was dyed purple, a color that enhanced the object’s royal affiliation because purple was associated with Roman-Byzantine emperors.

Chinese feng huang bird (end panel), Troyes Casket, Middle Byzantine, Constantinople (?), ivory and purple pigment, 13 x 26 x 13 cm, Cathedral Treasury, Troyes France

It is not known how this medieval Chinese motif found its way into the Middle Byzantine iconographic repertoire, or what it might have meant to Byzantine viewers. Perhaps the feng huang evoked the farthest reaches of the known world and anticipated Byzantine imperial expansion to these distant peripheries. Maybe the Byzantines were familiar with the significance of the feng huang in medieval Chinese lore as a supernatural harbinger of golden ages of rule. While we may never know precisely what significance this exotic motif held, the feng huang on the Troyes casket exemplifies the intercultural connections of medieval Byzantium and the art it produced.

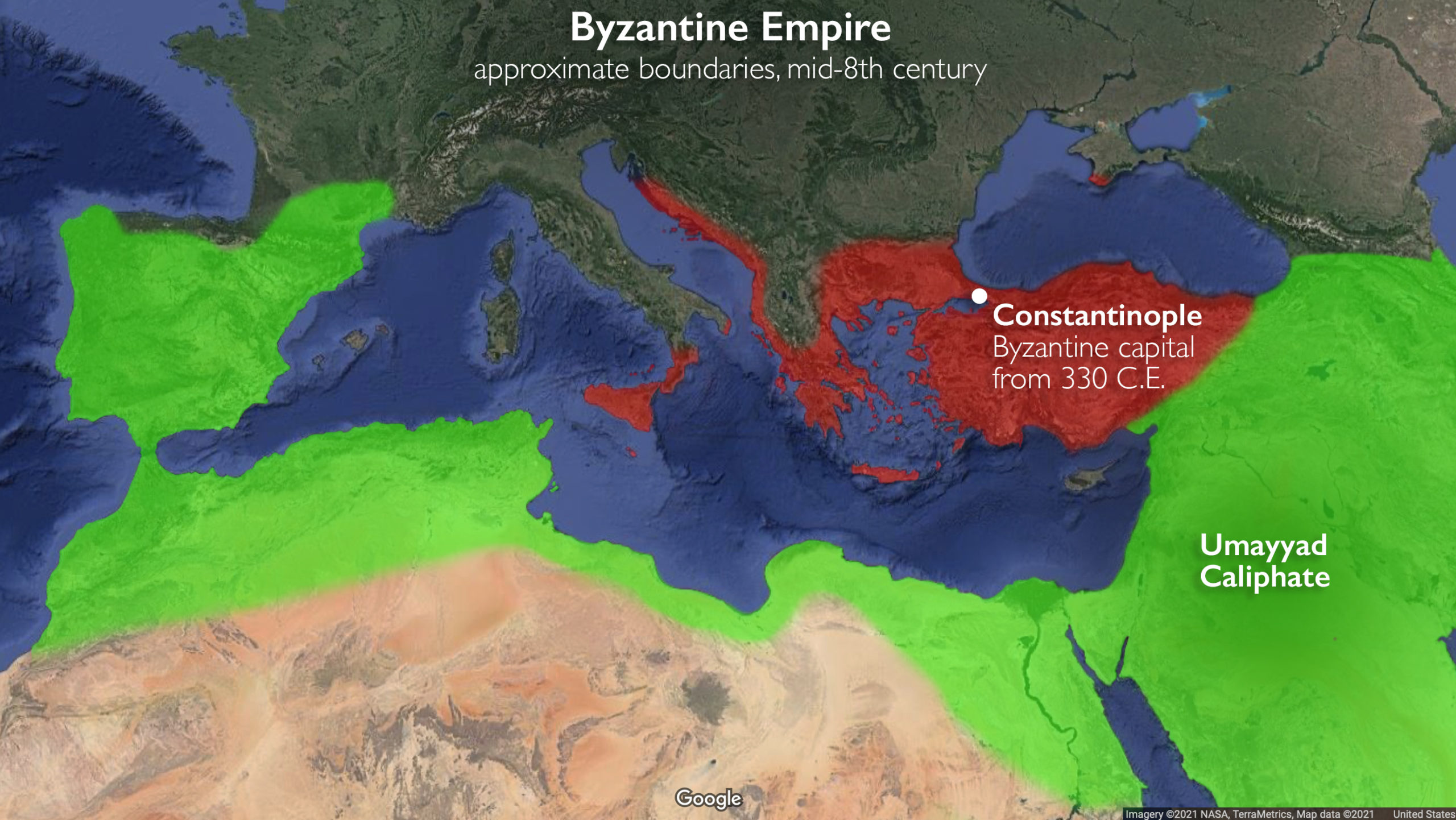

As the boundaries of the Roman-Byzantine Empire gradually constricted over the period of Late Antiquity (c. late third to mid-eighth century C.E.), the Byzantines found themselves in contact with an ever expanding range of cultural groups. Following the rise of Islamic armies in the seventh centuries, extensive eastern regions of the Byzantine Empire were lost to Islamic conquerors. Many territories across North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean coast were never recovered, and from the seventh to early thirteenth century Byzantium struggled to preserve its eastern borders against diverse rivals, especially newly emerging Islamic polities. Simultaneously Byzantium faced perennial challenges to its political authority from the North and West, with Western and Eastern European adversaries periodically vying for control of territories at the Empire’s edges.

These military conflicts occurred in tandem with diplomacy, and objects frequently played a role in intercultural negotiations. An eleventh-century text produced at the Fatimid (medieval Islamic) court in Cairo (Egypt), The Book of Gifts and Rarities (Kitāb al-Hadāyā wa al-Tuḥaf), includes detailed accounts of the wondrous gifts exchanged with Byzantium, including silk garments and hangings, precious metal vessels, and exotic animals. While the exact objects described in this text are not preserved today, surviving examples of these categories of luxury objects give shape to these verbal accounts.

Roundel (Orbiculus), Egypt, 7th–9th century, tapestry weave in polychrome wool and undid linen, 23 x 22.7 cm (©Dumbarton Oaks)

For example, Byzantine silks depicting animal and hunter motifs were favored as diplomatic gifts to Islamic rulers because their iconography referred to a shared value for the reverence of nature and the pleasures of elite pastimes.

Silk fragment with imperial hunters (Mozac Hunter silk), Byzantine, possibly 8th or 9th century (Musée des Tissus, Lyon; photo: Pierre Verrier)

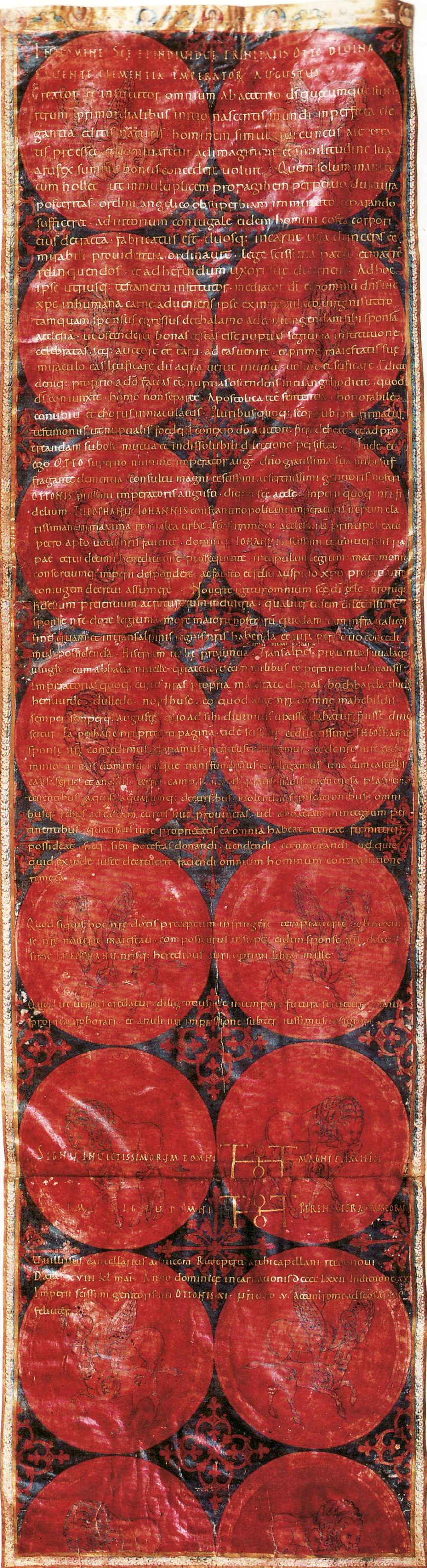

Diplomatic relations also included the exchange of people. The Book of Gifts and Rarities and medieval historical accounts document the presentation of enslaved people, the exchange of prisoners, and the transfer of conquered people across medieval Afro-Eurasia. These individuals sometimes included craftsmen, who helped to spread artistic knowledge, styles, and technical skills. In some instances, diplomatic relations were secured through marriage alliances that entailed the transfer of brides. In 972, Theophano, niece of the Byzantine emperor, was wedded to Otto II, heir to the Holy Roman Empire. Their union was commemorated with an Ottonian marriage contract that, alluding to Byzantine tradition, was written in gold on richly purple-dyed parchment and decorated with animal motifs in roundels, which resemble ornamental patterns found on precious silks.

Marriage contract of Emperor Otto II and Theophano, Ottonian, 14 April 972, parchment, black and gold ink, c. 155 x 40 cm, Niedersachsisches Staatsarchiv, Wolfenbüttel, Germany (Wikimedia Commons)

Theophano was a tastemaker at the Ottonian court. Having carried with her works of Byzantine art, she helped to transmit Byzantine artistic models and forms to medieval Western Europe. An ivory plaque depicting Theophano and Otto portrays them in typical Byzantine fashion, their union (and rule) affirmed by Christ himself.

Otto II and Theophano crowned by Christ, Byzantine-Ottonian, 982-983, ivory, c. 19 x 11 x 1 cm (Musée de Cluny)

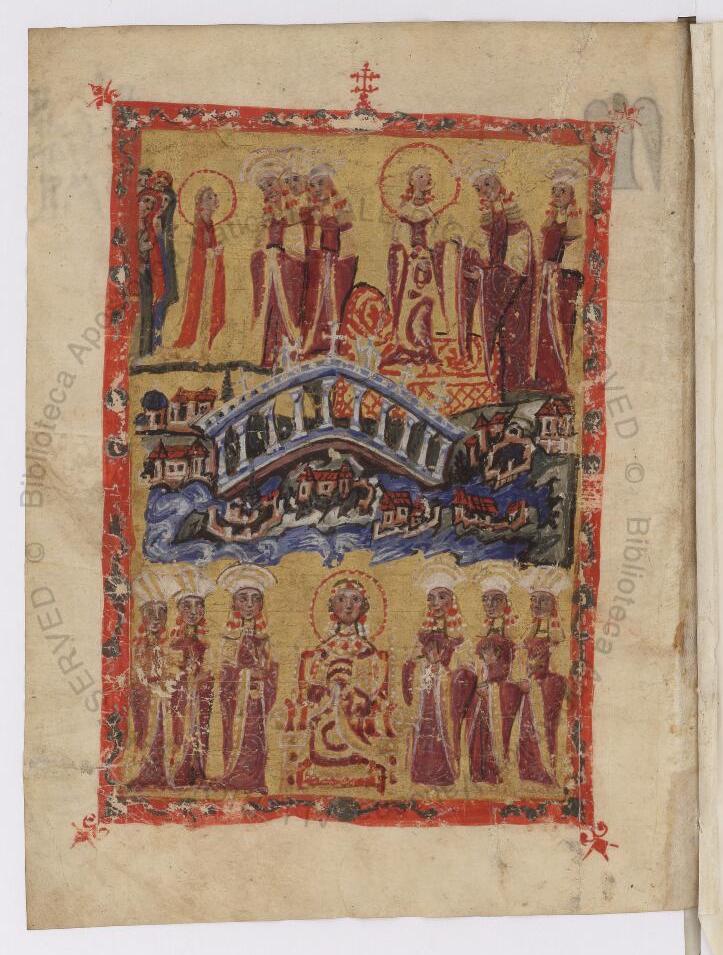

Foreign women also married into the Byzantine royal family to secure alliances. This Byzantine manuscript (Vatican cod. gr. 1851) depicting a foreign child-bride might celebrate the betrothal of Agnes of France (daughter of the French king Louis VII ) to Alexios II (son of the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos) in 1179. It includes illuminations, one of which visualizes the young woman’s metamorphosis into a Byzantine princess through the transformation of her regalia (in the upper register, between the images from left to right) and her culminating appearance enthroned in imperial splendor (lower register, at center). [1]

A foreign bride (with a red-outlined halo) arrives in simple attire (upper left corner) at Constantinople (depicted in the middleground); she is subsequently transformed into a Byzantine princess through changes in her garments (as depicted in the upper right, where she is received by women of the imperial court, and the lower center, where she is enthroned). Vatican City, Vatican Library, cod. Gr. 1851, Fol. 3v.

Elite Byzantine women were also wed to Islamic potentates. For instance, in the eleventh and twelfth century, Byzantine women who married into Seljuq aristocratic families served as conduits for the transfer of Byzantine material culture. These women typically retained their Orthodox Christian identities, passing on their language and faith to their children and helping to generate intercultural social spheres at the Seljuq court.

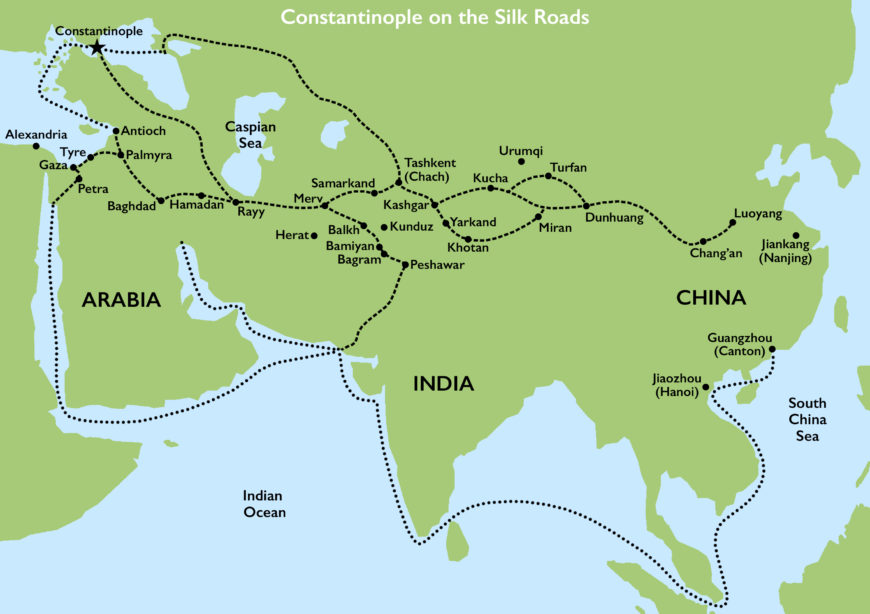

Map showing Constantinople (upper left corner) in the network of trade routes that made up the Silk Roads, adapted from Françoise Demange, Glass, Gilding, and Grand Design: Art of Sasanian Iran (224–642) (New York: Asia Society, 2007) (Evan Freeman, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As a result of military confrontations and diplomatic interactions, Byzantium was in persistent communication with a diverse range of other societies. In many cases, periods of peaceful relations led to economic cooperation that promoted intercultural trade. Constantinople (the capital of the Byzantine Empire) occupied a firm position as a major terminus point of the famed Silk Road, receiving a rich array of raw substances and finished goods that had traveled via Central Asia from China, India, and beyond. The ninth- or tenth-century code for the regulation of guilds in Constantinople, The Book of the Eparch (the eparch being the commercial administrator of the city) names a guild dedicated to the trade in goods from the East, so-called bagdadikia (things from Baghdad, the capital of Islamic Abbasid Empire) and sarakenike (things from the East or from “Saracen” [i.e., Islamic] lands).

Islamic ceramic vessels (glazed sgraffito and splashware) recovered from the Serçe Limanı shipwreck off the coast of Turkey, eleventh century (© Institute of Nautical Archaeology)

Trade goods transported by sea could travel rapidly but at high risk. An early eleventh-century Byzantine shipwreck discovered near Serçe Limanı off the coast of Turkey contained both Byzantine and Islamic objects, including Fatimid ceramic and glass vessels but also Byzantine and Fatimid coin weights, indicating that the crew was interacting with markets across a broad commercial and cultural network.

Glassware recovered from the Serçe Limanı shipwreck off the coast of Turkey, eleventh century (© Institute of Nautical Archaeology)

In addition to finished goods, its cargo included several tons of cullet (broken glass) of Fatimid origin that served as ballast (cargo of substantial weight that helps to stabilize a ship). Less energy was required to melt recycled glass than to produce glass from scratch, and it is thought that cullet originating from Fatimid territories along the Syrian-Lebanese coast was being shipped for recycling at a Byzantine center of glass production.

Cullet (glass waste) recovered from the Serçe Limanı shipwreck off the coast of Turkey, eleventh century (© Institute of Nautical Archaeology)

Intercultural artistic and commercial connections spurred changes in Byzantine fashion, as expressed through personal objects such as clothing, jewelry, and seals. Finished garments of Islamic origin were among the goods imported to the markets of Constantinople. Items of clothing typical of medieval Islamic dress—like the turbans and caftans—were popular in Byzantium, especially in border communities like Cappadocia, at the eastern edge of the Byzantine Empire.

Portrait of the donor, Theognostos (left) , wearing a turban, Middle Byzantine, c. 1050, wall painting, Çarikli kilise, Göreme (Cappadocia), Turkey (photo: © Robert Ousterhout)

Byzantine jewelry incorporated foreign motifs, including pseudo-Arabic (decorative forms that resemble Arabic letters but are illegible).

Bracelet with repoussé pseudo-Arabic motifs within a scrollwork frame, 11th century, silver-gilt and niello, diam. 6 cm, (© Benaki Museum)

Silver bracelet with decorated with griffin motif in repoussé and niello, 11th c., diam. 6 cm (photo: © Benaki Museum)

In addition, exotic animal motifs were found in Middle Byzantine jewelry as well as on lead seals. The Byzantines authenticated contracts, letters, and even containers of trade goods with lead disks attached to strings, which were then impressed with an inscription relating to the seal owner. As such, lead seals served as a surrogate for their owners and were intimately tied with personal identity and authority. These seals often included images. Exotic animals such as the senmurv (an ancient Persian mythical beast prevalent in Sasanian and medieval eastern Islamic art that combines the head of a dog, the body of a lion, the wings of an eagle, and the tail of a peacock) and the feng huang on Byzantine seals may have been intended to project the cosmopolitan identities of their owners.

Seal of Theodore (left: obverse; right: reverse) depicting a senmurv, 11th century, lead, diam. 1.6 cm (© Dumbarton Oaks)

Seal of John imperial spatharokandidatos and dioiketes depicting the feng huang bird, 10th century, lead, diam. 2.4 cm (© Dumbarton Oaks)

Even as the Byzantines struggled to maintain their preeminent position in medieval geopolitics, their art and material culture continued to be an object of emulation throughout Afro-Eurasia. The Western European mendicant orders were inspired by the affective properties of Byzantine icons, and they imported Byzantine sacred art and artistic forms to the West.

Berlinghiero, Madonna and Child, Italian, possibly 1230s, tempera on wood, gold ground, 80.3 x 53.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

These images generated new styles in devotional painting by the thirteenth century, as evident in the work of artists like Berlinghiero, Cimabue, and Duccio, sometimes described as proto-Renaissance, who drew from Byzantine stylistic and iconographic models.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna and Child, c. 1290–1300, tempera and gold on wood, 27.9 x 21 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Some medieval Eastern European polities fashioned their religious and royal artistic images in the likeness of Byzantium. The church of the St. Sophia in Kyiv, founded by the Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise in the eleventh century, boasts a monumental mosaic and wall painting program in a Byzantine mode and is one of many works of art and architecture that records the robust intercultural relations between Byzantium and medieval Rus’. Byzantine objects and buildings encountered by conquering armies in former Byzantine territories were often converted to new purposes and assimilated with emerging artistic traditions. This is especially apparent in medieval Anatolia, where, beginning in the eleventh century, the Seljuqs repurposed Byzantine sacred and secular structures to serve new needs, sometimes incorporating fragments of Byzantine architectural elements into newly constructed monuments.

Horses of San Marco (ancient Greek or Roman, likely Imperial Rome), 4th century B.C.E. to 4th century C.E., copper alloy, 235 x 250 cm each (Basilica of San Marco, Venice)

Following the Sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, masterpieces of Byzantine imperial and sacred art were disseminated throughout the medieval world, especially to treasuries in Western Europe. Such items may have included the Troyes Casket (discussed at the beginning of this essay), although conclusive evidence of an object’s traveling in the hands of Crusaders is rarely attested. Documented examples of Crusader trophies include the sculptures of horses that adorned the façade of San Marco in Venice (which had previously been displayed in the Hippodrome in Constantinople) and the relics of the Passion of Christ (including the Crown of Thorns and fragments of the True Cross), which king Louis IX of France acquired around 1238 (after his cousin Baldwin II, the Latin emperor of Constantinople, used the relics to guarantee a loan from the Venetians). Louis paid the Venetians an exorbitant sum, which was said to be over five times what it cost to construct the Sainte-Chapelle, the royal chapel in Paris where Louis deposited the relics. Even as Byzantium’s political fortunes dwindled in the wake of the Fourth Crusade, the valuation of its visual and material culture remained high across Afro-Eurasia.