Following war with the Persians, this highly naturalistic sculpture was buried out of respect.

Kritios Boy, from the Acropolis, Athens, c. 480–470 B.C.E., 4 feet high, marble (Acropolis Museum, Athens). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

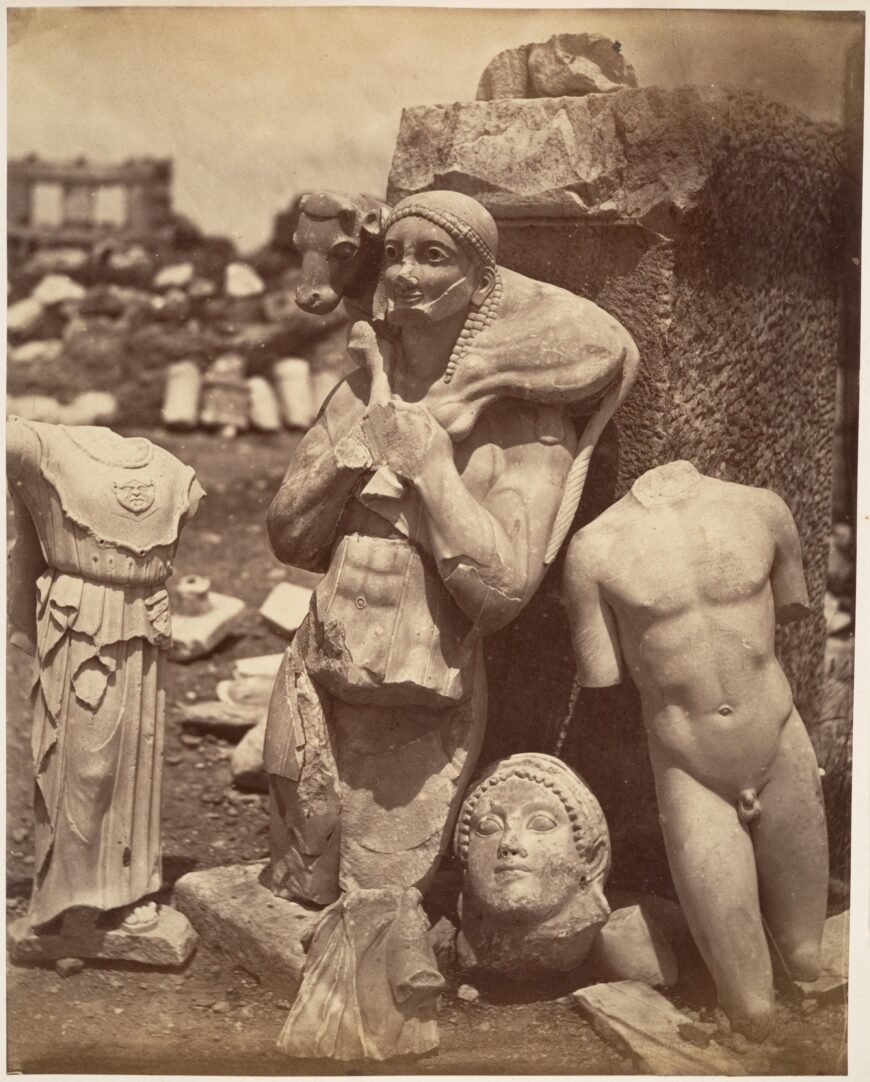

Photo of objects found on the Acropolis in Athens in the early 1860s (with the torso of the Kritios Boy visible at right), 1865, albumen silver print from glass negative, 27.7 x 21.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The head and torso of a famous ancient Greek sculpture were found separately on the Acropolis in Athens, in two different pits that were filled with dirt, rubble, and fragments of other statues. In the late 1800s, Greek architects and archaeologists who were preparing to build a new museum on the Acropolis discovered many ancient sculptures buried in such pits. [1] Ancient Athenians created these pits during the Classical period, sometime after the Persians invaded Athens and damaged the Acropolis in 480 B.C.E. While working to maintain and restore the Acropolis, they collected damaged statues and various pieces of refuse and buried them in pits across the sacred site. [2] Since the filling of these pits is composed of elements made at many different dates, it is difficult for archaeologists to determine when precisely the statues found within them were made. As a result, art historians and archaeologists still debate when one statue of a young nude boy that was found in two pieces was created. This statue, today known as the Kritios Boy, has a new sense of movement and liveliness that was not often seen in the Archaic period, suggesting that it was probably made in the earliest years of the Classical period, sometime between 480 and 470 B.C.E.

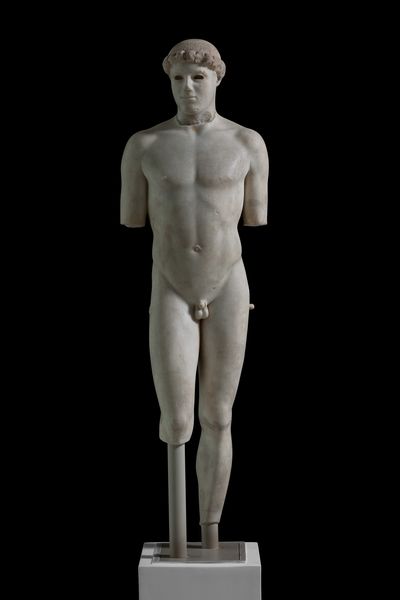

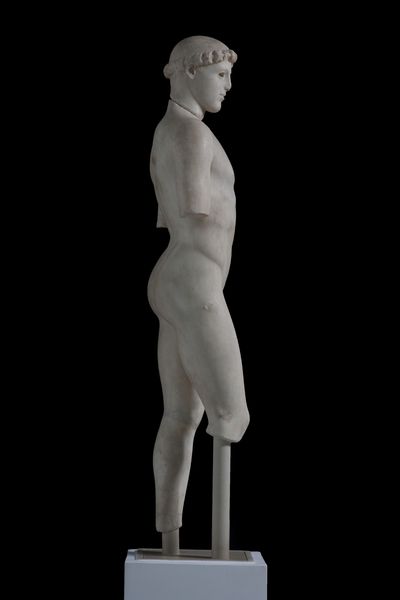

Kritios Boy, c. 480–470 B.C.E., marble, 4 feet high (Acropolis Museum, Athens)

From stiff steps to realistic shifting

The Kritios Boy is an under life size statue of a nude boy. In the Greek Archaic period, relatively rigid statues of nude young men known as kouroi (singular: kouros) were popular, and the Kritios Boy continued their lineage. Like most Archaic kouroi, the Kritios Boy is idealized and lacks easily identifiable individualistic characteristics, making it difficult to tell who exactly he represents. [3] However, he is far less stiff than his Archaic predecessors, such as the Anavysos Kouros.

Since the lower halves of the statue’s legs are not preserved, we can not tell exactly how they were positioned, but their imbalance is implied in the shifting movement of the Kritios Boy’s body. His right leg is bent and placed slightly ahead of his left leg, so that his left leg carries most of his weight. Reacting to this imbalance, his right hip is slightly lower than left hip, and his left shoulder is slightly lower than his right shoulder. This posture that shows the body in realistic movement is known as contrapposto. As he shifts his weight, the Kritios Boy appears to be on the brink of motion, preparing to take a step forward.

Left: Kritios Boy, c. 480–470 B.C.E., marble, 4 feet high (Acropolis Museum, Athens); right: Anavysos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Contrapposto is not apparent in Archaic kouroi. Comparing the Kritios Boy to a kouros made about 50 years earlier, during the Archaic period, reveals how much more naturalistic the Kritios Boy’s posture is. Both sculptures represent nude male youths with one leg advancing. The Anavysos Kouros places his left leg in front of his right, but his body remains completely stiff. His hips do not shift at all, nor do his shoulders. Instead, his upper body and arms remain perfectly still and symmetrical, embodying the Archaic ideal. In contrast, the Kritios Boy’s entire body shifts as he appears to move his weight off his right leg and onto his left leg, as if he is about to walk. His head turns to the right, making him appear more alert and lively. The movement in his hips and shoulders make his motion more believable. Even without knowing the original position of the Kritios Boy’s feet, we can appreciate the realistic imbalance that his shift in weight enacts. [4] This increased naturalism in the sculpture’s posture suggests that he was made after the end of the Archaic period, in the Early Classical period.

Head (detail), Kritios Boy, c. 480–470 B.C.E., marble (Acropolis Museum, Athens; photo: Marsyas, CC BY-SA 2.5)

Early Classical style

More Early Classical stylistic features are apparent in the head of the Kritios Boy. Although his eyes are now hollow, they would have once been inlaid with glass or stone, which would have made the statue appear more lively. [5] The Kritios Boy’s expression is serious, with no hint of the smile we see in many Archaic figures. He has thick eyelids, flat cheeks, and a large chin. His hair is elaborately styled, with individual strands rolled up over a fillet that encircles his head. All of these physical characteristics of the Kritios Boy’s head are typical of the Severe Style, a representational style that was especially popular during the Greek Early Classical period. This too suggests that the Kritios Boy was sculpted after the end of the Archaic period.

Left: Head (detail), Kritios Boy, c. 480–470 B.C.E., marble (Acropolis Museum, Athens; photo: Marsyas, CC BY-SA 2.5); right: Kritios, head of one of the Tyrannicides (Harmodios), Roman copy (c. 100–200 C.E.) of Greek original (c. 477/476 B.C.E.), marble (National Archaeological Museum, Naples; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Kritios and the Kritios Boy

Kritios Boy, c. 480–470 B.C.E., marble, 4 feet high (Acropolis Museum, Athens)

The Kritios Boy also resembles a few other sculptures made during the Early Classical period, which further implies that he was made during that era. One such sculpture represented the Tyrannicides, two Athenians who were celebrated by their fellow citizens after they killed a tyrant who ruled Athens in the Archaic period. The Tyrannicides sculpture was made by two artists named Kritios and Nesiotes. Today, only Roman copies of the original Greek sculpture of the Tyrannicides survive, but there is a resemblance between the head of one of the men—the one sculpted by Kritios—and the head of the Kritios Boy. By looking more closely at the head of the Tyrannicide originally made by Kritios and the head of the Kritios Boy, we can better understand their similarities. The boys have similar flat cheeks, heavy chins, and thick eyelids. They have different hairstyles, but similar serious expressions. These similarities have led some scholars to suggest that the sculpture found on the Acropolis in the late 1800s was made by the artist Kritios, resulting in his modern name being the Kritios Boy. However, since no original Greek sculptures definitely sculpted by Kritios survive, we must be cautious when associating the statue found on the Acropolis with him. The Kritios Boy may have actually been made by a follower of Kritios, or someone working in a style quite similar to that of Kritios. [6]

Although we can’t be sure that the Kritios Boy was sculpted by Kritios himself, we can still appreciate the statue’s stylistic innovations. Rather than taking an impossibly rigid step forward like his Archaic predecessors, the Kritios Boy shifts his weight believably. His body curves realistically in response to his imbalanced posture. Since the Kritios Boy was found only partially preserved in a backfill with a jumble of other statues made at different times, we can’t rely on archaeological context to tell us when exactly he was made. Instead, we must rely on stylistic analysis to determine his date of creation. [7] The Kritios Boy’s naturalism, as well as his Severe Style facial features and expression, suggest that he was made during the Early Classical period, as a new representational style began to replace the relatively stiff style of the Archaic period.

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:00] We’re in the new Acropolis Museum in Athens, looking at the “Kritios Boy.”

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:09] We’re in the very late Archaic period. Some call this the Severe Style. We might even call this early Classical.

Dr. Zucker: [0:16] It’s really this transition between the late Archaic and the early Classical, and the sculpture is such a great embodiment of that.

Dr. Harris: [0:22] It allows us to see the transition between the Archaic kouros and the much more naturalistic movement-filled figures that we find on the Parthenon, for example, in the frieze or in the metopes.

Dr. Zucker: [0:33] This sculpture was probably broken originally when the Persians invaded Athens and desecrated the Acropolis. This was a huge blow to the Greeks, and when they finally recovered this territory, they took the sculptures that had been destroyed and they buried them.

[0:52] It’s ironic that the reason that these sculptures are preserved is in part because they were destroyed. To make the story even more complicated, before the Greeks had been defeated by the Persians, they had an earlier victory at Marathon.

Dr. Harris: [1:01] Where an overwhelming force of Persians was defeated.

Dr. Zucker: [1:05] Now, that first victory by the Greeks over the Persians is important to understand in relationship to the sculpture, because some art historians have suggested that the newfound naturalism that we see in the sculpture is a result of the new sense of self-determination that came in the wake of the victory over the Persians.

Dr. Harris: [1:30] A sense of Athens as the leader among the Greek city-states who united against the Persians.

Dr. Zucker: [1:37] Like the earlier kouros figures, this is marble, it’s a standing nude. He’s relatively still, although there is this potential for movement.

Dr. Harris: [1:47] With the kouros figures, you had a figure that was both standing still and moving simultaneously, but here we have incipient movement. Movement about to take place — we have a sense of process. I think it’s that unfolding of time, that makes this figure seem so much a part of our world, instead of the timeless world of the kouros.

Dr. Zucker: [2:01] Well, the kouros figures were depicted as stick figures, there were mechanical joints that were suggested, but did not really exist.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] Didn’t really work.

Dr. Zucker: [2:09] Well, that’s right, there was no way for those figures to actually move. Whereas this figure, the much more naturalistic renderings of the volumes of the body, the understanding of the musculature, the understanding of the bone structure, and especially the transitions from one part of the body to the next, make the potential for movement believable.

Dr. Harris: [2:28] Although we don’t see the feet and the right side, we don’t see the calf, there is a sense that this figure is standing in a pose that art historians call “contrapposto.” That is, his weight is shifted onto one leg, and here’s the important part: as a result, other things happen within the body, so that one shift in one part of the body affects the rest of the body, so the body acts in unison.

Dr. Zucker: [2:50] We can see that very clearly with the knees. The weight-bearing knee is higher than the free-leg knee, and that’s because that knee droops down a little bit. The axes of the hips are no longer aligned. The weight-bearing leg has a hip that juts upward into the torso, where the free leg, the hip hangs down.

Dr. Harris: [3:09] The shoulder above the weight-bearing leg actually drops down slightly, and that compresses the torso in between. His lifelikeness is carried into the head, which shifts a little bit so we don’t have that strict frontality that we saw in the kouroi. The symmetry of the body is broken.

[3:26] In actuality, human beings are never symmetrical. Our bodies move and shift.

Dr. Zucker: [3:31] That’s why the kouroi seem so artificial.

Dr. Harris: [3:33] Exactly. They seem transcendent and timeless, but because the “Kritios Boy” is asymmetrical, we have a sense of his engagement with the world. Gone is that Archaic smile that seems to transcend reality.

[3:45] One of the really interesting things about the “Kritios Boy” is that, if we look from the side, we see an arch in his back, and there’s a sense that he’s moving forward and holding himself back at the same time. He’s a bit of a tease.

Dr. Zucker: [0:00] Well, he’s in a very relaxed pose.

Dr. Harris: [3:59] We should mention that the Greeks had started to make bronze sculptures just before this, and bronze allowed artists to create sculptures with limbs more separated from the torso, or limbs lifted into space.

Dr. Zucker: [4:11] And you can see why that could be tricky in marble. In fact, this figure has lost its leg, and it’s lost its arms. On his left hip, you can still see a fragment of the strut or bridge that would have helped support the arm that would have been next to it. It also lets us know that the arm really was at his side, very much like a traditional kouros.

Dr. Harris: [4:31] So we see the desire on the part of the Greeks, on the part of this artist, to create a sculpture that’s more open, where the limbs and the torso are more separated from one another, but in marble, that’s really hard to do.

Dr. Zucker: [4:43] One more point about the interest in bronze. Unlike so much marble sculpture, here we have eyes that have been hollowed out. They would have been inset, probably with glass-paste eyes that would have been very lifelike, and that’s a technique that was commonly used in bronze.

[4:59] In traditional marble sculptures, you actually have the eyes part of the solid piece of marble, and they would have just been painted.

[5:05] There is this interesting reference to the technique of bronze casting, even here in a marble sculpture. I should mention that the reason we call it the “Kritios Boy” is because the Kritios sculptor was an important sculptor in bronze at this time, of which this is very stylistically similar.

[5:22] In the entire body, we’ve moved away from the linear representation of symbols of the body, and we now have these smooth, beautiful volumes that represent this Greek ideal of the athletic male youth.

Dr. Harris: [5:34] That represented the peak of human achievement, and also the qualities of the divine.

[0:00] [music]