Egyptian mythology and religious beliefs evolved and morphed over time. There was no official “holy book,” nor was there an “authorized version” of the stories gathered together into a single text. Instead, the study of Egyptian religious beliefs requires piecing together visual and written sources into a lived experience. This evidence is also surprisingly fragmentary. For instance, for many periods and regions we lack surviving temples (chief sources for ritual representations and texts) and domestic settings (rich sources of shrines and evidence of day-to-day religious practices).

One of the earliest types of religious texts to appear were topographical lists. These provided a list of deities and their cult places, with their functions and attributes indicated via epithets. Some of these epithets, such as Horus’s “protector of his father,” suggest that certain myths were already developed even though we have no written record of them from this early period. There was certainly a tradition of oral transmission that was already old by the time the Great Pyramid was built.

With more than 1,500 named deities, it is far beyond our scope here to discuss more than a fraction of them. Instead, below is a brief discussion of a few selected deities of various types to serve as a basic introduction to the Egyptian pantheon.

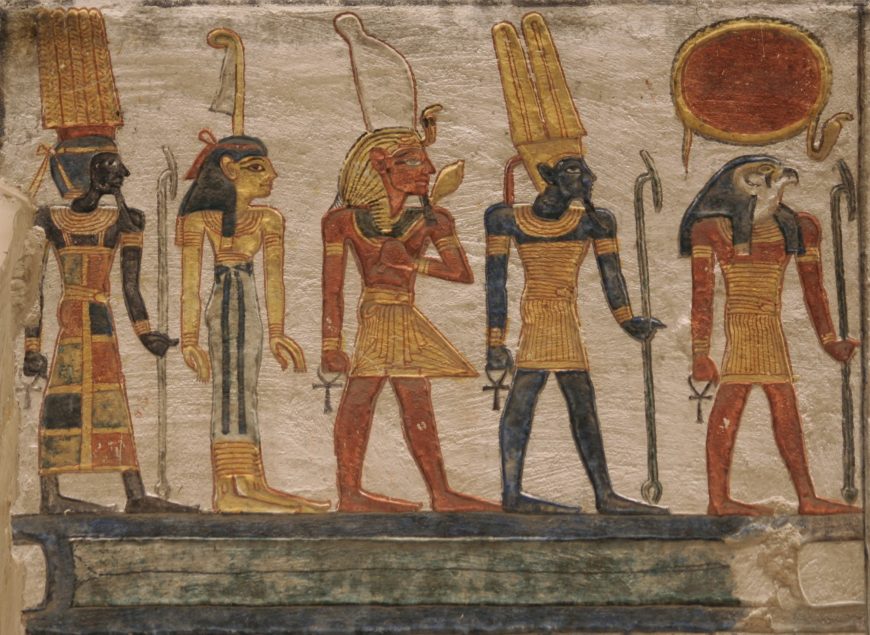

Ra / Amun-Ra

Arguably the most important deity in Egypt was the sun god Ra. He merged with other solar deities at an early date and assimilated them as aspects of himself—he was the emergent Khepri at dawn, Ra-Horakhti as the midday sun, and the weary Atum at the end of the day. Ra was a universal deity, who acted in the celestial, terrestrial, and netherworld realms, and was often presented as the supreme creator who emerged from the primordial waters at the beginning of time. As creator of the world, Ra was also the archetypal ruler of the cosmos; myths tell of how he reigned over the earth until he became weary of the task and departed for the heavens, leaving living kings, known by the title ‘Son of Ra,’ to rule in his stead.

When the god Amun rose in prominence in the New Kingdom, the two were fused to create the all-powerful Amun-Ra. His daily journey through the sky was fraught with dangers and he was accompanied in his sky boat by various deities who helped him on his path. In the Pyramid Texts, the king was said to join the entourage on the solar barque upon his ascension. His solar barque traveled the netherworld at night, passing through many challenges and merging with Osiris in the depths of the netherworld before emerging reborn at dawn.

As befitting a deity with so many aspects, Ra could be presented in many different forms, often simply as a sun disc wrapped with a protective cobra, but also in hybrid form as a male with a falcon, ram, or scarab head crowned by a sun disc. He was also manifested as various animals and could be represented as a ram, heron, serpent, bull, scarab beetle, lion, or cat (among other creatures, depending on the context). Iconographic devices, such as rows of discs and yellow bands displayed at the tops of walls or on ceilings, defined the symbolic path of the sun in temples and tombs. Solar symbols were integrated into many architectural forms as well; pyramids and obelisks were among the most prominent, but more subtle solar iconography was woven into nearly every Egyptian context.

Hathor

Hathor originated in the Predynastic period. She appears in the Pyramid Texts and later religious literature and holds a prominent place in the pantheon. Her name was written as Hwt-Hor, or “Mansion of Horus.” A sky goddess, Hathor was sometimes depicted in bovine form. Her main cult center was at Dendera, where a massive temple from the Ptolemaic period still stands, but she was worshiped in many locations throughout Egypt. She was connected to Ra as a strong, protective force, serving as an “Eye of Ra.” This role, which could be filled by several powerful goddesses, represented the dangerous aspects of the sun’s heat and helped to protect him. Sometimes, she was referred to as Ra’s consort who accompanied him on his daily journey through the sky. Called the “Golden One,” she usually wears a crown of a sun disk flanked with upright horns.

Also connected with sexuality, fertility, and motherhood, Hathor was the “beautiful one” who assisted women in all these realms. Most often represented in anthropomorphic form and wearing a red or turquoise dress, she was the mistress of the West who opened the gates of the underworld for the newly deceased and aided their transition. She was also presented as a hybrid figure with a human body and cow or composite head.

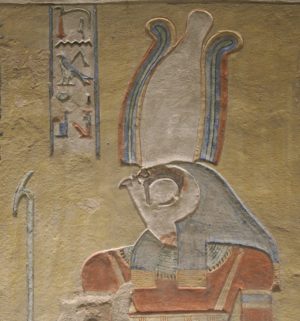

Horus

This falcon god was among the oldest known—Predynastic rulers were called ‘Followers of Horus’ in later texts and he appears on early ceremonial objects like the Narmer Palette. His complex nature is evident from the various aspects and roles he played in myth. Called ‘Lord of the Sky,’ Horus was viewed as a celestial falcon; these birds were highly revered for their sharp-eyed capabilities. This aspect was probably the earliest form in which he was worshiped, such as at the site of Hierakonpolis. Connected to this was his role as a solar deity and he was called Horakhty or “Horus of the two horizons’ as god of the rising and setting sun. Horus came to be worshiped as the son of Osiris and Isis, although the origins of this connection are obscure. In both falcon form and as the divine son of Osiris and Isis, Horus was strongly associated with kingship—kings were often referred to as a “living Horus.”

Diorite statue of King Khafre (Chephren), 4th Dynasty, Old Kingdom, Giza, Egypt (photo: kairoinfo4u, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

From the Early Dynastic period, the king’s name was written in a rectilinear form, known as a serekh, which was topped with a falcon. His role as guardian of kingship is beautifully demonstrated in the famous statue of an enthroned Khafre with the Horus falcon wrapped protectively around the back of his head.

As son of Osiris and Isis, Horus was heir to the mythical throne of Egypt and in pharaonic ideology the living king became associated with the falcon god while his deceased predecessor became Osiris, Lord of the Underworld. Horus was depicted in several forms: zoomorphically as a falcon, anthropomorphically as an adult or child god, and, most commonly, as a hybrid of a falcon-headed male wearing the Double Crown, signifying his rule over a united Egypt.

Osiris

One of the most important of all Egyptian deities, Osiris was prominent in pharaonic ideology and also popular in religion. He probably originated as a fertility god and was associated with the Nile inundations that rejuvenated the land. Viewed as a ruler of Egypt in the most ancient period, stories tell of his chaotic brother Seth slaying and dismembering him, scattering those pieces throughout the land. His powerful consort, Isis, gathered those pieces together and created the first mummy. Through her formidable magic, she revivified him and conceived their miraculous son, Horus. Horus avenged his father and Osiris became the King of the Underworld, providing a model for the desired resurrection that was the goal of every Egyptian.

In royal ideology, the deceased king was associated with Osiris while his living heir was viewed as the new Horus on the throne. Dwelling in the depths of the netherworld, Osiris served an essential role in the daily rejuvenation of the sun god Ra; he was even viewed as a counterpart of Ra for the dead, bringing them renewed life. Usually represented anthropomorphically as a shrouded wrapped mummy, often with green or black skin to suggest fertility, and grasping icons of kingship—the crook and flail.

He is often shown wearing a special crown called an Atef, which looks like a White Crown flanked by feathers. He is connected with the djed pillar from an early date; this hieroglyph came to be viewed as the stable backbone of the god. He served as the judge of the dead, sitting enthroned and viewing the weighing of the heart that awaited each deceased Egyptian. Eventually, the dead of all classes were referred to as an “Osiris.”

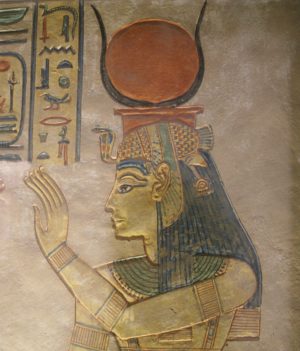

Isis

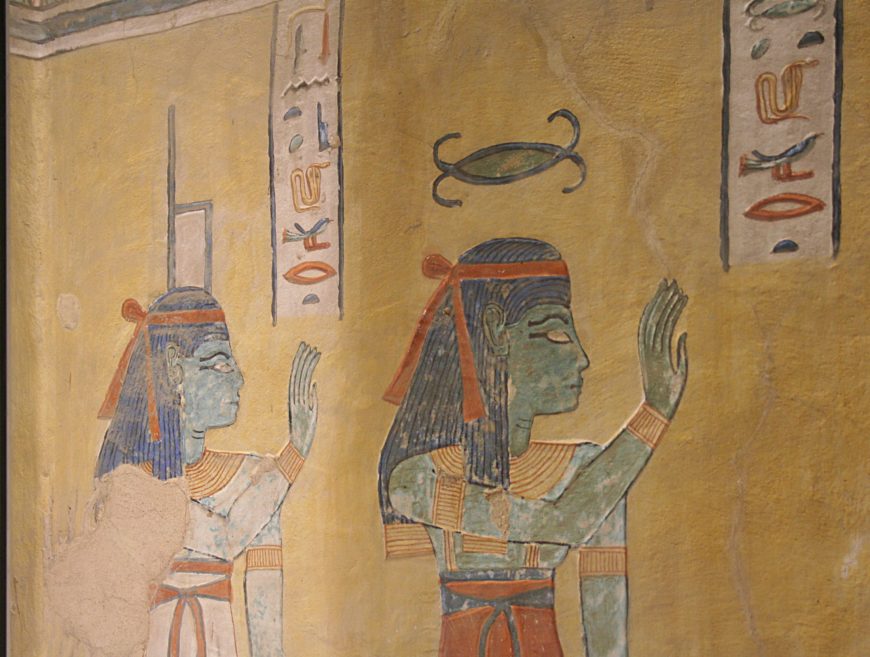

Almost always shown in anthropomorphic form, Isis was an extremely important goddess in Egypt and beyond. Sister-wife of Osiris, she appears more than 80 times in the Pyramid Texts assisting the deceased. She and her sister Nephthys were associated with kites (a scavenging bird of prey that has a shrill cry); they were portrayed as the archetypal mourners of the deceased. The primary protector of Horus, literally hundreds of thousands of statues were produced showing her holding the infant Horus on her lap.

Isis was the symbolic mother of the king and she may have originated as a personification of the power of the throne—her name is written with the sign for “throne’”and she is often crowned with this emblem. Like several other powerful goddesses, Isis could serve as an “Eye of Ra.” She was ‘Great of magic’ and her abilities in this realm are often emphasized. In addition to using her powerful magic to revivify Osiris and enact the conception of Horus, another story relays how she used her magic to heal Horus from a scorpion sting. She was often invoked in spells of protection and healing. One fascinating myth tells of how she used magic to learn the secret name of Ra, gaining dominance over him by that knowledge. On her head, Isis usually wears either the throne hieroglyph or a sun disc and horns. Sometimes she has wings, especially when her arms are outstretched to protect the figure of Osiris. A protective amulet associated with Isis, called a tyet, was used by the living and also often placed in mummy wrappings.

Her famous temple on the island of Philae was the last functioning Egyptian temple and her worship there continued until the 6th century C.E. Isis’s influence outside of Egypt (such as in ancient Rome) was substantial. She was connected with other goddesses, such as Astarte and Aphrodite, and had temples at Byblos, Athens, and Rome. Her cult was one of the “mystery religions” practiced throughout the Greco-Roman world; evidence of her veneration has been discovered as far away as England.

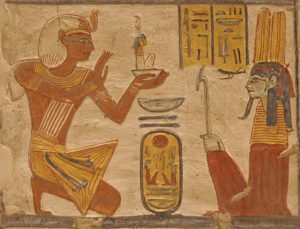

Ma’at

This goddess personified the concepts of justice, truth, and cosmic order and is generally represented in anthropomorphic form wearing a tall feather on her head. She existed from as early as the Old Kingdom and appears in the Pyramid Texts. She was associated with Ra and also Osiris, who was called ‘lord of ma’at,’ and was generally identified as the consort of Thoth. Ma’at’s connection to the king was vital — the ruler gained legitimacy through their capabilities in maintaining cosmic balance and they were often called ‘beloved of Ma’at.’

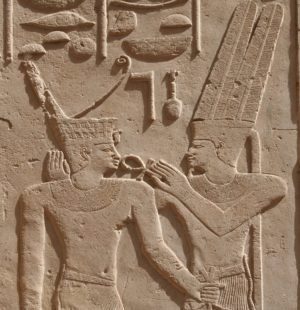

Many images show the king presenting a small figure of Ma’at to other gods, especially Amun, Ra, and Ptah, as an affirmation of the ruler’s ability to maintain order and also as sustenance for the gods similar to food offerings; some texts explicitly state that the gods ‘live on Ma’at.’ She also represented judgment and the feather of Ma’at was placed opposite the heart of the deceased on the scales at their final judgment. If the heart was heavier than the feather, the deceased was truly damned; if the heart was lighter than the feather of truth, the blessed dead could enter an idealized afterlife in the Field of Reeds.

Amun

Amun was first mentioned in the Pyramid Texts along with his consort, Amunet, and the pair were also part of the Ogdoad representing the element of “hiddenness.” He became the primary local god of the Theban region during the 11th Dynasty, with a series of kings who took the name Amenemhat (Amun is pre-eminent), and eventually rose to the supreme position in the pantheon during the New Kingdom, having been merged with the sun god as Amun-Ra. His early shrine at Karnak expanded greatly over time and became the largest religious complex on the planet. He was associated with the goddess Mut and the moon god Khonsu was worshiped as their son. Although grouped as the Theban Triad, each had their own sacred spaces within the Karnak complex.

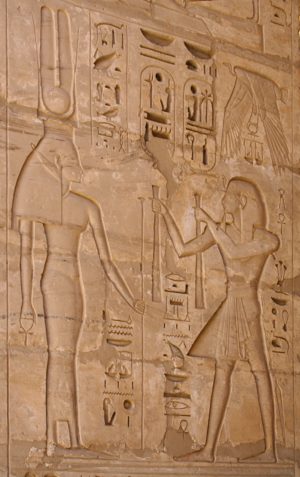

Not only part of the Ogdoad, Amun was also represented as a primary creator god and his Karnak temple was said to house the “mound of the beginning,” where he brought the world into being. He was associated with the sun as Amun-Ra and was also viewed as a powerful fertility god. In this aspect, he was called ‘Amun-Min kamutef’ (literally “bull of his mother,” suggesting he begot himself with the sky cow goddess) and was depicted in ithyphallic form in many ritual scenes at Karnak and Luxor temples. Amun was first called “king of the gods” on the White Chapel of Senusret I at Karnak and this title became commonly applied to him. In later periods, he was associated with the Greek god Zeus. Regularly depicted in anthropomorphic form with blue skin, he was shown wearing a short kilt, bull tail, and a crown with a flat-topped base and a pair of tall feathers. He was also shown in hybrid form with a human body and the head of a ram with curved horns.

Mut

Although her origins are unclear and the first certain mention of her doesn’t occur until the end of the Middle Kingdom, Mut became the great mother goddess and queen of the gods from the New Kingdom onwards. She replaced Amunet, Amun’s original consort from the Ogdoad, and became his chief wife. Her name was written as a vulture, the word mwt which meant “mother,” and she was usually identified with the living queen as mother of the king.

The vulture headdress commonly worn by Egyptian queens is a reference to Mut. Atop her vulture headdress, Mut is often shown in anthropomorphic form wearing the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt and holding a papyrus topped staff. She was also closely connected with the lioness, especially in her fierce aspect as a protective “Eye of Ra,” and was sometimes portrayed with a leonine head. She had a connection with violent justice as well; a fearsome punishment of fire in the “Brazier of Mut” awaited any rebels or traitors to the throne. Generally, her influence was focused on the world of the living and she played little role in the afterlife; there is evidence for a great deal of personal veneration of this “Great Mother” by the population.

Seth

Originally a desert deity, Seth represented chaotic and destructive forces. Sometimes paired with the falcon god Horus, he appears on Predynastic objects and also figures prominently in the Pyramid Texts. By the Middle Kingdom, he had assumed a position on the front of the solar boat to help repel the chaos serpent Apophis that threatened the sun god’s daily journey. Seth was depicted as an enigmatic long nosed canid with squared ears and an upright forked tail or as a hybrid of a human body with the head of this animal. His title ‘Red One’ linked him to the desert lands as did his wild temperament; in general, he was linked with violence, conflict, and rebellion. Seth stood in opposition to his brother Osiris, who represented the fertile ‘Black Land’ of the Nile valley. According to myth, Seth murdered his brother and tore his body into pieces. Later, he struggled in a series of conflicts with Horus, the son of Osiris and Isis, engaging in vicious acts including tearing out Horus’s eye. Eventually, Horus triumphed over his uncle and claimed the throne. Seth’s fearsome character came to be associated with storms, sickness, disease, crime, foreign invasion, and other evils in the world.

Anubis

An early, important funerary deity, Anubis was connected with burial and afterlife—he is mentioned dozens of times in the Pyramid Texts in this capacity. He fulfilled this role for all deceased Egyptians, presiding over mummification and protecting burials. He was placated in the hope that he would control the scavenging desert dogs who had the habit of digging up shallow graves and scattering the bodies; a horrific fate for any Egyptian.

Usually depicted as a black canid or a human with a jackal head, his black coloration was symbolic of regeneration. Anubis was called ‘Foremost of the Westerners’ (i.e. those in the land of the dead) and ‘Lord of the Sacred Land’ signifying his supremacy over the desert cemeteries. Often depicted attending the mummy in its tomb (a role that may have been played in the terrestrial realm by human priests wearing jackal masks, several of which survive), he was called ‘Master of Secrets’ due to his connection with embalming. One of his main functions was to lead the deceased before Osiris and perform the Weighing of the Heart at their final judgment.

Ptah

One of the oldest gods, attested as early as the First Dynasty. His primary cultic location was Memphis, which was the administrative seat for most of Egypt’s history.

Generally represented in anthropomorphic or mummiform wearing a blue cap crown, his consort was the fierce lion-headed goddess Sakhmet. The god of craftsmen, Ptah was a chthonic creator being, sometimes called “the sculptor of the earth.” He is usually shown as mummiform, connecting him with funerary and afterlife realms, often standing on a small base in the form of the hieroglyph for ma’at, or “truth.” Ptah was venerated as far south as Nubia and his image is one of four sculpted at the rear of the temple of Ramses II at Abu Simbel along with the deified king, Amun-Ra, and Ra-Horakhti. This temple was designed so that twice a year the rays of the rising sun penetrated deep into the temple and illuminated this group statue. However, while the sun lights up the other three images, the creator god Ptah stays forever in darkness.

Sakhmet

A fierce leonine goddess, Sakhmet had two distinct sides to her personality—she could either be destructive and dangerous or aggressively protective. She was the quintessential ‘Eye of Ra’ who protected her father, the sun god, from his enemies. Sakhmet was also his preferred instrument of destruction. One myth tells of a time when Ra became tired of humans plotting against him and he sent his ferocious daughter to punish them; she became so blood-thirsty and enamored with her task that she nearly brought about the complete destruction of humanity before the other gods were able to reign her in (by getting her drunk with red-dyed beer she mistook for pool of blood). Sakhmet was said to breathe fire at her enemies and she became the primary protector of the king, especially in battle. However, her breath was also capable of bringing pestilence—Sakhmet had to be propitiated and a special ritual known as ‘appeasing Sakhmet’ was performed to combat epidemics. If she was appeased, she could bring healing instead of plague. Amenhotep III commissioned hundreds of black granite statues of the goddess to be set up in temples around Thebes in an apparent attempt to keep her happy. Usually regarded as the consort of Ptah and worshiped primarily at Memphis, she also had temples in many other areas. Sakhmet was usually represented in hybrid form as a woman in a red dress with the head of a lioness (see the image directly above) wearing a long wig and sun disc atop her head.

Neith

An ancient goddess, Neith appears to have been one of the most important prehistoric deities and her worship extended to the very end of Egypt’s history. Her mythology is complex.

She was a warrior goddess, associated with hunting, weapons, and warfare—one of her earliest emblems includes a pair of crossed arrows atop a pole—and she served as an ‘Eye of Ra.’ Much later, she was connected with the Greek goddess Athena. She also had a creator aspect and was part of the primeval waters; some texts even describe her as creating Ra and humankind calling her ‘the eldest, mother of the gods.’ As such, she was also seen as an archetypal mother figure and was said to support women in childbirth. Her connections to Lower Egypt are evident by the regular representations of her as an anthropomorphic female wearing the Red Crown. Her other common identifying headgear was the distinctive symbol that was used for her name. A funerary deity who protected the deceased, she was also believed to be the inventor of weaving and provider of mummy bandages and shrouds.

Nut

Personification of the sky, Nut was a member of the Ennead and daughter of Shu and Tefnut. She was the mother of heavenly bodies, who swallowed the sun each night and birthed the disc again each morning. In this cosmic view, the sun god traveled through her body each night and the stars were similarly absorbed during the day. She may have been specifically associated with the Milky Way, stretched across the heavens. Given the perceived solar journey, it is not surprising that Nut became closely connected with the concept of rebirth. From early in Egypt’s history, she also served this function for the deceased and is mentioned nearly 100 times in the Pyramid Texts as an agent of resurrection.

She was often portrayed frontally and outstretched on the interior lids of coffins and sarcophagi to aid in this process. Nut is generally shown in anthropomorphic form, sometimes with a water pot on her head, but could also be represented as a sky cow, with her four hooves being the cardinal points and the stars and sun god sailing across her belly. In anthropomorphic form, she is often shown nude and in profile in relief, with her body arched over the earth god Geb and her body full of stars. Some of the most magnificent representations of her appear on the ceiling of the burial chamber of the tomb of Ramses VI in the Valley of the Kings where a pair of colossal images were painted back to back. These represent the day and night sky and show the sun disc making its journey through her body to emerge at dawn.

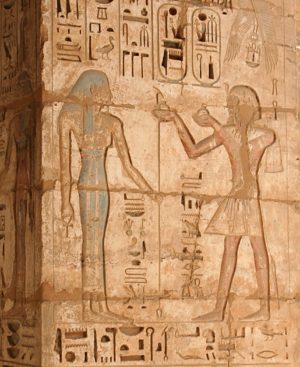

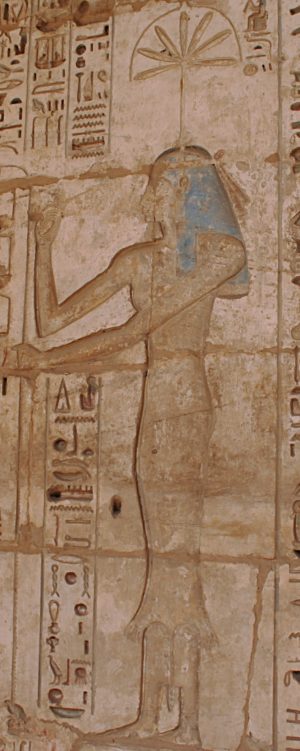

Seshat follows behind the king and records millions of years for his reign. Memorial Temple of Ramses III at Medinet Habu

Seshat

The goddess of writing, accounting, and notation, the “female scribe” (as her name is translated) was patroness of temple libraries. Beginning from the 2nd Dynasty, Seshat was responsible for establishing the ground plan in the foundation of sacred structures and was called the “mistress of builders.” She also kept records of the booty and tribute taken by the throne as well as being responsible for tracking the king’s regnal years and jubilee festivals, which she inscribed on palm ribs and the leaves of a sacred tree.

She was shown in anthropomorphic form as a woman wearing a leopard skin dress and an enigmatic symbol on her head that resembles a seven pointed star topped by a crescent shape.

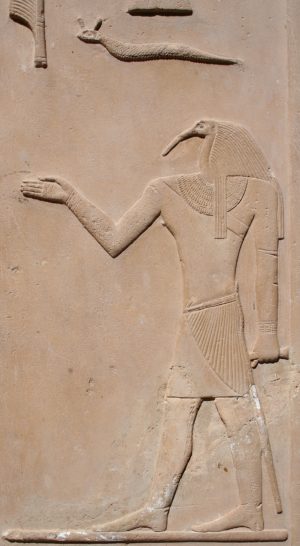

Thoth

Originally a moon god, Thoth came to be associated with knowledge and was said to have invented writing. Shrewd and skilled, he became connected with scribes and scholars. He kept records for the gods, acting as their scribe, and also served as the patron for all areas of written knowledge. Many temple scenes show him recording the events that are depicted or tallying the offerings being presented. In the afterlife, he stood next to the scales that weighed the heart of the deceased and recorded the verdict.

Widely venerated, Thoth was worshiped in many areas of Egypt and the many thousands of votive ibis mummies discovered in these cult locations illustrate his popular appeal. Viewed as truthful and straightforward, Thoth was usually represented in hybrid form with a male body and head of an ibis. He could also be depicted in animal form as an ibis and also as a baboon, sometimes crowned with a lunar disc and crescent. Mentioned frequently in the Pyramid Texts, often in association with Ra, Thoth was sometimes referred to as the ‘night sun’ in juxtaposition with the solar deity. Through his knowledge and magical abilities, he was said to have healed the eye of Horus after Seth plucked it out. He often acted as an intercessor and messenger between the gods; in later times, he was associated with the Greek god Hermes.

Nekhbet

This vulture goddess was the tutelary deity of Upper Egypt. She and the cobra goddess Wadjet, who was connected with Lower Egypt, were the Two Ladies — together, they represented the united Egypt. Nekhbet was usually depicted wearing the White Crown of Upper Egypt and she was considered a mother of the king. Almost always represented as a vulture with her wings outstretched, she often frames the shen sign of eternity between her wings or grasped in her talons.

Wadjet

Connected with the delta region of Lower Egypt from the earliest times, the cobra goddess Wadjet (‘the Green One’) was paired with the vulture Nekhbet to signify the Two Lands. She was closely linked with the king as a fierce protector — ‘Mistress of Fear,’ she was the ubiquitous cobra perched on the king’s brow who spat fire at his enemies. She also protected the gods; even during the Amarna period when many other deities were avoided, she was shown as a protective element on the sun disc itself. Almost always depicted as an upright cobra, Wadjet was sometimes fused iconographically with Nekhbet as a vulture with a cobra head.

Bes

This complex and enigmatic figure may really represent a series of supernatural beings that were eventually merged. Although little is known about his origins, Bes became one of the most popular and widespread of Egyptian deities. By the New Kingdom, he was accepted by all classes of society as a fiercely apotropaic being who was especially connected with the protection of pregnant women, women in childbirth, and young children. He was often represented alongside the goddess Taweret in this role.

His appearance is unique and seems to have originated in the form of a dwarf wearing a lion skin or as a lion standing upright on its rear paws. He is usually portrayed frontally, even in relief, as a squat figure with short legs, a tail, and an enlarged head with a lion mane and a projecting, lolling tongue. He often wears a plumed headdress. Regularly depicted in amuletic form or carved on cosmetic items, musical instruments, apotropaic wands, headrests, and beds, his fierce protective image also appeared painted in rooms of royal palaces and even on the king’s chariots. Bes was widely venerated in household shrines and his popularity spread well beyond Egypt, appearing in Cyrus and Assyria.

Taweret

The “Great female one,” Taweret appeared as early as the Old Kingdom. She is usually represented as a hippopotamus standing upright with a swollen, pregnant belly and pendulous breasts and the paws of a lion. Often, her mouth is open in a wide grimace, emphasizing her protective function and she usually wears a long wig with a flat modius crown, feathers, or a sun disc with horns.

Protector of pregnant women, her primary attributes are the ankh, symbol of life, and the sa, emblem of protection, which were usually oversized and placed at her sides with her paws resting on the top. One of the most popular household deities and commonly revered in household shrines, Taweret seems to have had no formal temple cult. She was often paired with Bes and also appears on headrests, cosmetic items, apotropaic wands, and amulets.

Hapy

The personification of the river Nile, particularly related to the annual inundation and the fertility it brought. A manifestation of divine order, Hapy was referred to as a creator god that helped maintain cosmic balance. This deity was the ‘Lord of the fishes and fowl,’ with many riverine forces being portrayed as their attendants. Usually depicted androgynously or as a male with a swollen belly and pendulous breasts, Hapy displayed a clump of papyrus and lotus clusters on their head.

Often represented with blue or green skin, sometimes with wavy water signs carved into the flesh. Hapy is shown on colossal statues of the king as twinned figures tying together the heraldic plants of Upper and Lower Egypt around the sema hieroglyph representing ‘union.’ Rows of Hapy figures often appear in temple relief bringing the bounty of the land as offerings.