The Amorites were the Indigenous people of central inland and northern Syria. They spoke a Semitic language related to modern Hebrew. During the Early Bronze Age (3200–2000 B.C.E.), they developed powerful states such as those centered on Ebla, Carchemish and Aleppo. Enclosed behind large fortification walls, these cities had elaborate palace and temple buildings. The Amorites maintained close diplomatic and trading relations with cities in Mesopotamia to the east and south. This contact is reflected in their art and architecture which is often influenced by that of Mesopotamia. The cuneiform writing system was also adopted from southern Mesopotamia to write the local Semitic languages. In addition, however, the Amorite city-states maintained trading links with Canaan and Egypt.

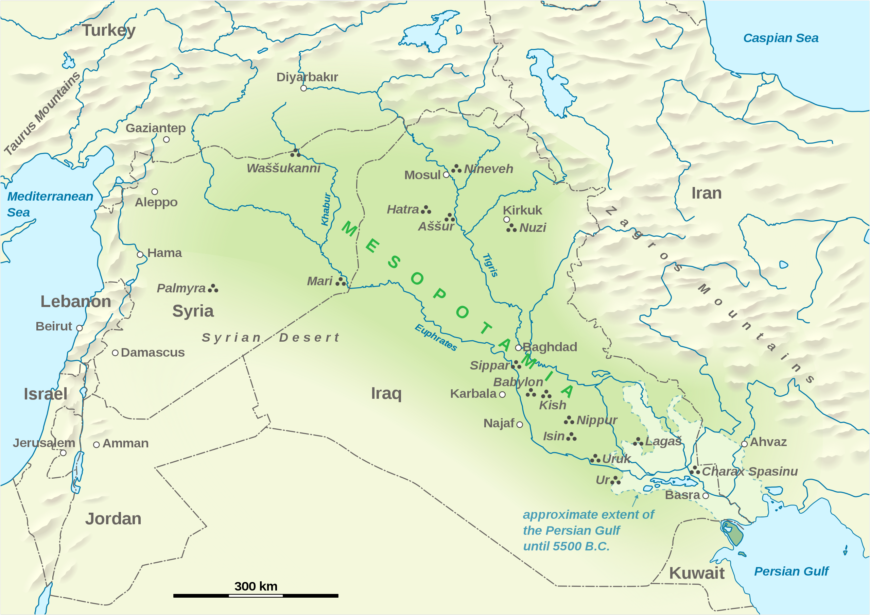

Map showing the extent of Mesopotamia (map: Goran tek-en, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Many cities in Syria, including Ebla were destroyed around 2300 B.C.E., possibly as part of the military expansion of the kings of Akkad from southern Mesopotamia. Recovery was swift, however, and by the end of this period many Amorites had moved southwards along the Euphrates river and settled throughout Mesopotamia. By 1900 B.C.E. dynasties of Amorite rulers had come to control many important cities in this region, including Mari and Babylon, whose most famous king was Hammurabi (1792–1750 B.C.E.).

During the second millennium, the Amorite population of Syria fell under the control of the Hittite Empire, and only when this empire collapsed in the twelfth century B.C.E., did the Amorites re-emerge as a vibrant and energetic people, known as the Aramaeans.

Pottery juglet, Amorite, about 2400–2000 B.C.E., from the Middle Euphrates region, Syria (© The Trustees of The British Museum)

Pottery juglet

This juglet, with its applied figurine, is pierced at the base and may have been a strainer. Alternatively it could have been used a sprinkler, by clamping a thumb over the top when the vessel was filled with liquid, then withdrawing it gently and so releasing the pressure.

Much of the Middle Euphrates region now lies beneath the waters of a lake. Between 1963 and 1973 an international rescue mission excavated many sites in the area, which was threatened by flooding as a result of the construction of the Tabqa dam. These excavations revealed a distinctive regional culture.

During the period from about 2400 to 2000 B.C.E., northern Mesopotamia and Syria appear to have been dominated by a number of expanding sites. Mari on the Euphrates and Ebla (modern Tell Mardikh, south-west of Aleppo) were among the most important. Over 8000 inscribed clay tablets discovered at Ebla show close contact with Mari and indicate that the site wielded extensive political power. Contacts with cities in the south of Mesopotamia were also significant. At the end of the third millennium B.C.E. King Sargon, or Naram-Sin, who was ruler of Agade, one of these southern cities, campaigned into the north and destroyed Ebla, thus changing the balance of power.

Hematite cylinder seal of Habde-Adad, Old Babylonian Dynasty, about 19th century B.C.E., from Mesopotamia, 2.4 cm high (© The Trustees of The British Museum)

Hematite cylinder seal of Habde-Adad

The design on this cylinder seal shows a typical scene of the nineteenth century B.C.E. of a presentation to a god. A king carries an animal offering, while behind him stands a goddess or lamma. A lamma is often shown leading the worshipper before the god but here she stands with her hands raised in prayer. The god holds a knife or saw, identifying him as Shamash, god of the sun and justice.

The cuneiform inscription identifies the seal owner as ‘Habde-Adad, servant of the king Ibiq-Adad’. At the time in northern Mesopotamia, around Babylon and Eshnunna, various Amorite and West Semitic princes were gaining control of cities. Ipiq-Adad II was an Amorite ruler whose dynasty had taken control of Eshnunna, north-east of modern Baghdad. He began to use seals with typical Babylonian designs.

The seal was part of a collection of antiquities assembled by Claudius James Rich, the first British Resident in Baghdad in the early years of the nineteenth century. Rich’s collection formed the foundations for The British Museum’s Mesopotamian collection in 1825.

© The Trustees of The British Museum