Related works of art

In the Ancient Mediterranean

Masks

Active in c. 5000 B.C.E.–350 C.E. around the World

In North Africa

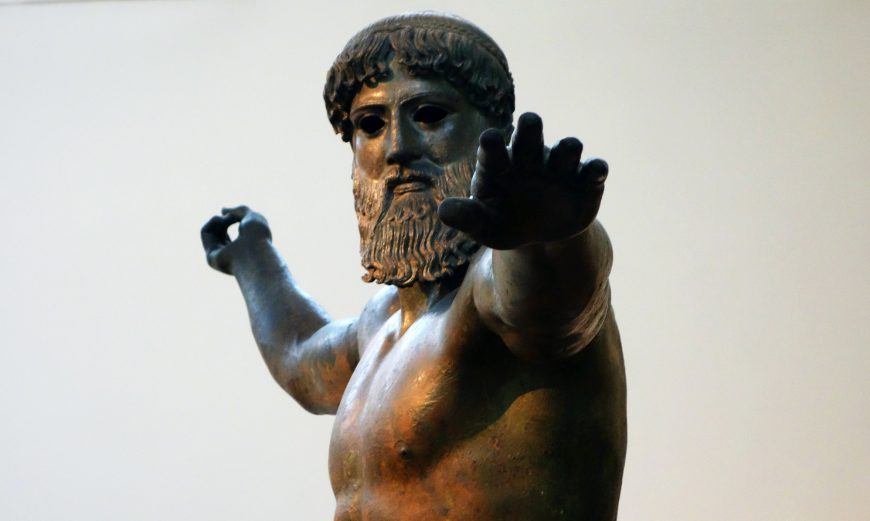

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer)

Greek original c. 450–440 B.C.E.; Roman copy before 79 C.E.

Italy

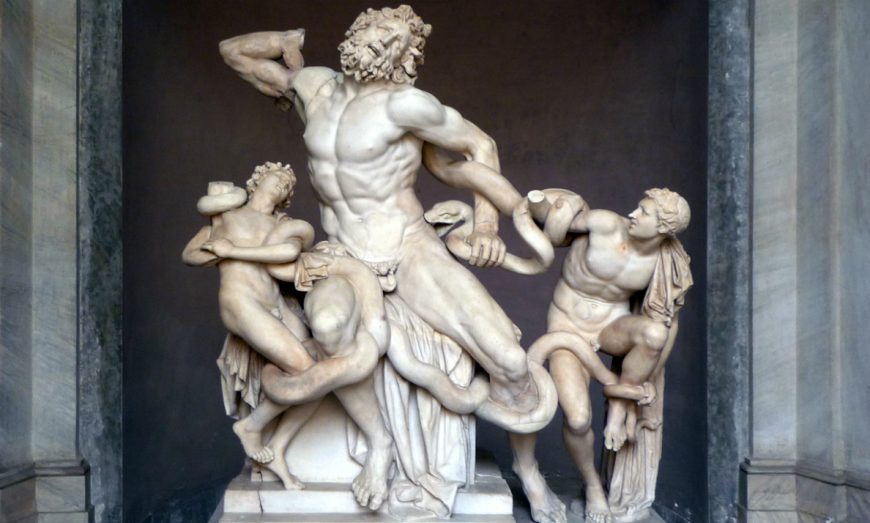

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons

early 1st century C.E.

Italy

A moment in time that’s lasted 2,000 years— the Spinario (Boy with Thorn)

c. 1st century B.C.E.

Greece

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!