Left: Gold coin depicting Julia Domna (detail), part of a ceremonial vessel, 209 C.E.; right: Ceremonial vessel (patera, 25 cm in diameter) featuring gold coins of emperors and empresses of the Antonine and Severan dynasties. The central image has a mythological scene of Bacchus, the god of wine, and Hercules, a semi-divine hero. Found in 1774 at Rennes (Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris)

A traveling empress

On a journey to Britain, Julia Domna supposedly spoke to a Celtic queen about a scandalous topic: the love lives of Roman and Caledonian (Scottish) women. Ancient authors likely invented this conversation to make a point about women’s morality, but Julia Domna certainly visited Britain on one of the many trips she took across the Roman empire.

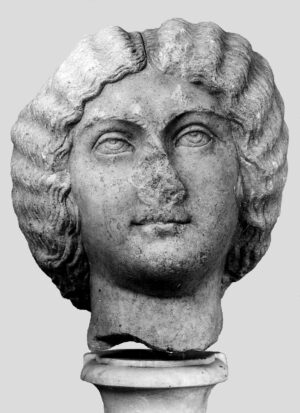

Portraits help us imagine what the residents of Britain and other regions saw: a woman with a dramatic profile and an extremely elaborate hairstyle. Historical sources describe her intellectual and cultural leadership, but Julia Domna’s own perspective is lost. We only know what others thought of her.

In Britannia (the Latin name for the Roman province of Britain), Julia Domna and her husband the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus were a long way from home. She had been born in Emesa (modern Homs, Syria) and he had been born in Lepcis Magna (modern Khoms, Libya). They married in 187 C.E., when he was a Roman general moving around the empire to govern different territories. After he was acclaimed emperor in 193 C.E., he became Rome’s first ruler from Africa (193–211 C.E.), and she became Rome’s first empress from Asia (193–217 C.E.). More than any prior imperial couple, they traveled together as Severus continued to make ceremonial visits and lead military campaigns.

Like many empresses, Julia Domna was honored with statues commissioned by local communities and on coins issued by the Roman Empire’s mints. As a result, her portraits have been found throughout the Roman empire and even beyond its borders.

Portrait of Julia Domna (from Ostia, Italy), c. 203–217 C.E., marble, 175 cm high (Museo Ostiense, Ostia, Italy, inv. no. 21; photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0). Excavated in 1939, near building IV.VII.II (Caseggiato della Fontana con Lucerna), Ostia

A portrait statue from Ostia, Italy

One of her best portraits comes from Ostia Antica, Rome’s port city on Italy’s western coast.

The empress stands in a balanced pose called contrapposto. If you look closely at her elegant clothing, you will see that a tunic gathers beneath her neck and pools around her sandalled feet, and a mantle wraps around her head and body. The folds of the fabric cast shadows up, down, and around the statue, and the drapery only reveals some parts of the body’s shape, such as the bent knee. The fabric was strategically sculpted to protect the limbs from breaking off by connecting the arms to the torso and the legs to the base.

Her face combines both real and ideal features. In the wrinkles running from the nostrils to the corners of the lips, there is a hint of age. Yet the broad forehead, smooth skin, and slight smile conform to general ideals of beauty, as do the enlarged eyes. Incised irises and pupils focus the empress’ gaze and give her a sense of presence.

Portrait of Julia Domna (with an earlier hairstyle), c. 193 C.E., marble, 29 cm high (Museo Ostiense, Ostia, Italy). Excavated in 1939, near the Temple of Roma and Augustus and the Forum Baths (I.XII.VI), Ostia

Her hair falls in separate crimped and braided sections, which are gathered in a bun (chignon) behind her head. She favored this style in the later years of her reign. A more fragmentary portrait from Ostia shows her earlier hairstyle, without the layered braids. Both hairstyles are thought to combine ornate wigs (the crimped and braided sections) and living hair (the small curls on the cheeks).

The full-length statue includes important symbols. A slightly damaged diadem is visible at the top of the head. The well-preserved hand holds wheat stems and poppies associated with Ceres, goddess of agriculture.

Romans covered their heads as a sign of piety during religious ceremonies, so here we see an empress honoring a goddess essential for Roman prosperity while also promoting the feminine virtue of fertility.

Head and hands (detail), Portrait of Julia Domna (from Ostia, Italy), c. 203–217 C.E., marble, 175 cm high (Museo Ostiense, Ostia, Italy, inv. no. 21; left photo: myglyptothek: Faces of ancient Rome; right photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0). Excavated in 1939, near building IV.VII.II (Caseggiato della Fontana con Lucerna), Ostia

Portrait of Sabina, 137–38 C.E., marble, 1.86 m high (Museo Ostiense, Ostia, Italy, inv. no. 25). Excavated in 1909, Palaestra, Baths of Neptune (II.IV.II), Ostia

The statue may seem unique, but the body could belong to any elite Roman woman. Another statue from Ostia depicts the empress Sabina (117–137 C.E.) with an almost identical body, but a different face and hairstyle. Such repetition was common: Roman portrait statues reveal a small range of ideal body types, with identities expressed in faces and dedicatory inscriptions.

A key part of Julia Domna’s statue monument is missing. The small circular base was intended to fit into a taller pedestal with a dedicatory inscription. Pedestals for Julia Domna survive at Ostia, and they would have elevated the statue far above the heads of viewers. The pedestals were not found with the portraits, however, so it is hard to know which ones belong together. Statues and pedestals often become separated when sites experience catastrophes and later urban development, as Ostia did.

The empress on coins

Portraits and names survive together on coins, which can help us identify who is represented in statues that have lost their dedicatory inscriptions. Scholars use coins as a kind of identification card for emperors and empresses, even though appearances varied across media and changed over time.

Left: Coin depicting Julia Domna, 196–211 C.E., silver, c. 1.9 cm (York Museums Trust), found in 2016 at Overton, near York; right: Coin depicting Julia Domna, 196–211 C.E., silver, c. 1.9 cm, excavated in 1930 at Mosul (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

Coins were the most widespread medium for transmitting imperial portraiture, and Julia Domna appeared on tens of thousands of them. One found near Eburacum (York, England), is labeled with the name Iulia (spelled with an I in Latin) and the title Augusta (used by Rome’s empresses).

The portrait captures Julia Domna’s distinct profile and elaborate hairstyling, with a chignon, ridged waves, and even the small curl on the cheek. Another coin excavated at Nineveh (Mosul, Iraq), shows the empress with the same appearance and title. Whereas Mosul was on a frontier contested by Iran’s Parthian Empire, York was where the Severans lived during their lengthy stay in Roman Britain (208–211 C.E.). These two locations, separated by 3,200 miles (5,150 km), show how far images of the empress could circulate.

Julia Domna’s facial features and intricate hairstyle can also be recognized on dolls, public monuments, and family portraits. These formats reveal how her image was used in Roman society, and we sometimes know by whom.

An empress doll

Dozens of dolls survive from the Roman empire, and a few resemble empresses. The one most like Julia Domna was found in a tomb at Tibur (Tivoli, near Rome).

Doll resembling Julia Domna, c. 200 C.E., ivory, 30 cm high (Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo, Rome; left photo: Ryan Baumann, CC BY 2.0; additional photos by the author). Excavated in 1929 at Tivoli

The small figure was created with expensive materials: it was carved from ivory and wears a chain necklace, bracelets, and anklets crafted in gold. [1] The elongated body reveals the curved contours of the navel, stomach, and breasts. On the head, incised lines define the strands of hair as well as the irises and pupils of the eyes. The doll’s joints enabled dynamic movement, so that the miniature empress could be dressed and put in motion. Clothes would have been stored in the tiny amber box found in the same coffin.

The doll and the box may have belonged to a powerful priestess: near the coffin was a monument for Cossinia, who had been a Vestal Virgin in Rome.

Left: Northeastern façade of the tetrapylon honoring Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Geta, and Julia Domna, 203 C.E., stone (Khoms, Lepcis Magna, Libya; photo: Franzfoto). Excavated under Italian occupation, the collapsed monument is almost entirely reconstructed and includes replicas of the relief sculptures. The original sculptures have been housed in the local site museum and in the national archaeological museum in Tripoli. Right: Relief sculpture of Julia Domna and Geta from the northeastern façade of the Severan tetrapylon at Lepcis Magna, c. 203 C.E., stone, figures: 1.2 meters high (Jamahiriya Archaeological Museum, Tripoli, photo: William MacDonald). Excavated in the 1920s at Khoms (Lepcis Magna)

The empress on monuments

Julia Domna also appeared on several arch monuments, which was unusual for an empress. [2] A tetrapylon at Lepcis Magna depicts her repeatedly with her husband and their two sons (Caracalla and Geta). Her presence visibly ensures the family harmony necessary for a smooth transfer of power. In one fragmentary relief sculpture, she stands with her younger son Geta. Like the statue from Ostia, the relief sculpture depicts Julia Domna’s drapery and segmented hairstyle with different surface textures. The folds of her tunic and mantle, however, are deeper and more numerous here as they wrap around her turning body. This deep carving was an aesthetic preference and also made the figures more visible: this relief comes from the uppermost part of the monument.

The empress in color

A rare painting shows us Julia Domna, Septimius Severus, and their son Caracalla in full color. The painting’s original purpose is unknown, but it may have been used in a household shrine honoring the imperial family.

Severan Tondo, c. 200 C.E., tempera on wood, 30.5 cm diameter (Altes Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0). Purchased in 1932, no known findspot, but thought to be from Egypt

The artist followed the convention of depicting women and children with slightly lighter skin tones than adult men, but the image clearly captures Julia Domna’s dark eyes and hair. The painter used three shades of brown to represent the shape, texture, and volume of the hairstyle. Light and dark bands radiate away from her face, while visible brushstrokes in a middle shade are layered on top of them. These bands of unblended color capture a dynamic play of light and shadow that make the hair seem to shine and shimmer from a distance.

The painter also depicted elaborate jewelry for the empress: precious gems enrich the golden diadem, while pearls adorn the ears and neck. Aside from the ivory doll, which wears actual golden jewelry, such adornment rarely appears in sculpted portraits of empresses. Display contexts and social concerns about luxury may explain these differences.

The painting is important because it helps us imagine the coloring of Julia Domna’s stone portraits—tinting sculpture was common in the Mediterranean world. The painting also documents the family’s tragic reality.

When Septimius Severus died of ill health in 211 C.E (while the family was still in Britain), the two sons inherited power together. Arguments led Caracalla to execute Geta (allegedly in front of Julia Domna) and then to condemn remembrance of his brother (damnatio memoriae). This is the cause of Geta’s erasure from the painting. Coins depicting Geta nonetheless continued to circulate, and some sculpted portraits (such as those on the tetrapylon at Lepcis Magna) also escaped destruction.

The widowed empress and her death

Julia Domna’s prominence continued during Caracalla’s short reign (211–217 C.E.), and he even took the unprecedented step of leaving the seals of state in her hands when he traveled. This tangible power may explain why the widowed empress had the highly unusual honor of being named on several public monuments dedicated to her reigning son. The triumphal arch at Djémila (Cuicul), Algeria, is a good example.

Arch dedicated by the colony of Cuicul to Caracalla, Julia Domna, and the deceased Septimius Severus, Djémila, Algeria, 216 C.E. (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0). Reconstructed in 1922, during the French occupation

This political arrangement did not last long. Caracalla was murdered in 217 C.E., and Julia Domna died soon afterward, either from cancer or suicide. Her great-nephew Elagabalus, also of Syrian descent, eventually overcame usurpers to become emperor.

Mapping Julia Domna

By the end of her life, Julia Domna had lived in Syria, France, Italy, and Britain, and had traveled in eastern Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa. Even in places she had not visited, her image was present. Her portraits can now be found in museums around the world, but many come from the art market, and we do not always know where they were found.

The portraits from Ostia are especially valuable because they come from documented excavations, as do the coins from Rennes, York, and Mosul; the doll from Tivoli; and the relief sculpture from Lepcis Magna. [3] Portraits with known findspots are ideal for understanding how the empire’s residents used these representations, and they are essential for seeing how far dynastic images spread across the Roman realm.