Animal sacrifice played an important role in ancient Roman religion, but what was involved in the preparation?

![<em>Preparations for a Sacrifice</em>, fragment from an architectural relief, c. mid-first century C.E., marble, 172 x 211 cm / 67¾ x 83⅛ inches (Musée du Louvre, Paris) [note: the date for this relief from the Louvre's website—beginning of the second century C.E.—is at odds with the Louvre's publication of its catalog Roman Art and given the arguments of Koeppel and Torelli, the assignment of a date in the second or third quarter of the first century C.E. is more likely]](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/roman_sacrifice_louvre_700.jpg)

Preparations for a Sacrifice, fragment from an architectural relief, c. mid-first century C.E., marble, 172 x 211 cm / 67¾ x 83⅛ inches (Musée du Louvre, Paris) [note: the date for this relief from the Louvre’s website—beginning of the second century C.E.—is at odds with the Louvre’s publication of its catalog, Roman Art from the Louvre (2009) and given the arguments of Koeppel and Torelli, the assignment of a date in the second or third quarter of the first century C.E. is more likely]

An animal sacrifice

The scene depicts a group of four males and a bull preparing for a sacrifice. The bull, bedecked in finery—including its pelta-shaped frontalia—is the intended victim. One attendant (a tibicen) provides music by playing the flute (tibia), two others hold the bull, and the fourth is perhaps the officiant who will conduct the ceremony. The latter figure, wearing a toga, stands at the viewer’s far left, looking toward the sacrificing priests.

Ox (detail), Preparations for a Sacrifice, fragment from an architectural relief, c. mid-first century C.E., marble, 172 x 211 cm / 67¾ x 83⅛ inches (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Public sacrifices such as the one depicted in this relief played a major role in the Roman state religion. The animal sacrifice itself served multiple functions, chief among them honoring the divinity in question, but also providing a context within which ritual communal feasting could take place after the event. These communal feasts provided valuable nutrition to city dwellers and served to reinforce community ties within the locus of the sanctuary.

The scene is set against a sculpted background that depicts a Corinthian temple (to the left) and a distyle building (to the right) that has two Aeolian capitals flanking a double door; this latter façade is decorated with a laurel garland.

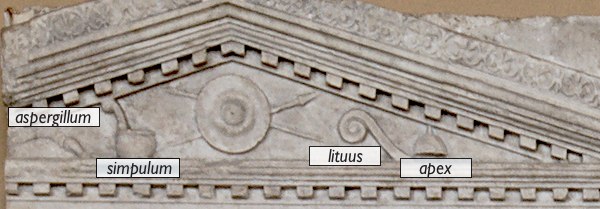

The temple’s pediment (see image below) includes depictions of various Roman ritual equipment including the aspergillum (for sprinkling sacred water), simpulum (a ritual ladle for libations), lituus (the curved wand of a religious official known as an augur), and an apex (a flamen’s hat). Such a background serves not only to situate the main scene but also to add realism and contextualization to these activities as they took place within the city of Rome.

Pediment (detail), Preparations for a Sacrifice, fragment from an architectural relief, c. mid-first century C.E., marble, 172 x 211 cm / 67¾ x 83⅛ inches (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

As we look closely, it’s important to keep in mind that the relief has been heavily restored—with art restorers adding elements to replace those that had been lost. Archival records suggest that the restorations were carried out by the sculptor Egidio Moretti in 1635, when the relief was a part of the collection of Asdrubale Mattei. The main restored elements are the heads of the two sacrificial priests, as well as the beard of the togate man. Also restored are the hands and the flute of the musician, the right portion of the bull’s frontalia, the bull’s muzzle, and the raised arm of the priest nearest to the bull. These restorations must all be considered to be conjectural.

Chronology

This fragmentary historical relief comes from Rome but unfortunately lacks a secure findspot (the relief was in the possession of the Mattei family when it was purchased by the Louvre in 1884). Objects such as this one—which was long ago removed from its archaeological context—are incredibly difficult to date.

Based on comparative stylistic analysis, the relief has been dated by some scholars to the beginning of Hadrian’s reign (117-138 C.E.), based upon its supposed similarity to the so-called adventus relief of Hadrian (now in the Capitoline Museums). If this reading is correct, the setting for the relief is the forecourt of the Temple of Concord (a temple in the Roman Forum), although this assignment is based on an undocumented impression that the relief’s findspot was in or near the Forum of Trajan. This is an important reminder that stylistic dating is subjective and often inaccurate.

Ara Pietatis, cast of the Della Valle-Medici slab, detail with scene of sacrifice before the temple of Mars Ultor, 43 C.E., marble, 3 feet, 9 inches high (original in the Villa Medici, Rome)

An alternative and more compelling argument promoted by G. Koeppel called for an earlier dating of the relief. Koeppel argued that the most apt stylistic comparison is a fragment of a relief from the Ara Pietatis Augustae (the Altar of Augustuan Piety, a Julio-Claudian monument from Rome’s Campus Martius, image above), which would place the date of the Louvre relief either at the close of Claudius’ reign (41-54 C.E.) or at the beginning of Nero’s reign (54-68 C.E.). Koeppel based his argument on a comparison of the architectural background visible in both reliefs, as well as on the stylization of the bull’s head in both reliefs.

Architecture (detail), Preparations for a Sacrifice, fragment from an architectural relief, c. mid-first century C.E., marble, 172 x 211 cm / 67¾ x 83⅛ inches (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Mario Torelli posits that the buildings in the background of the Louvre relief should be identified as the house of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (the father of the emperor Nero), at right, and, at left, Aedes Penatium, a temple once located on the Velia in Rome.

Context: historical art

It is clear that the creation of historical art forms—meaning those that aim to encapsulate and document actual events in a permanent medium—stands out as a key achievement within the vast corpus of Roman art. As a medium, historical relief sculpture defines public art of the Roman imperial period. These reliefs, most often carefully composed and well executed, capture the Roman interest in detailed depictions of actual events that had transpired. One clear outcome of creating such a corpus of sculpture is the creation (and reinforcement) of communal memories that served not only to remind the human participants and witnesses of things that they had seen but also to serve as a cohesive agent, binding together the constituent members to the body of the community.

The celebratory element of reliefs of this type remind viewers of communal rituals (in which some of them may well have participated) that occurred in the city of Rome on a regular basis, manifesting an interchange between state ritual and the urban populace. These reliefs also serve a didactic function, capturing snapshots, of a sort, to reflect the traditions, customs, and iconography of the Roman culture. In their hyper-detailed nature they are not only beautiful artifacts to behold today, but they also encode important documentary evidence that aids in our understanding of details large and small related to the Roman civilization.