Hospitality was key in ancient Rome, and this wall painting shows the gifts that guests may have received.

Still Life with Peaches and Water Jar (left), Still Life with a Silver Tray with Prunes, Dried figs, Dates and Glass of Wine (center), and Still Life with Branch of Peaches, Fourth Style wall painting from Herculaneum, Italy, c. 62-69 C.E., fresco, 14 x 13 1/2 inches (Archaeological Museum, Naples)

Hostess gifts

When I was growing up, my (proper, Southern) mother always insisted that I bring a hostess gift to my friend’s parents when I spent the night at their house. A typical teenager, I thought she was annoyingly old fashioned. This painting, Still Life with Peaches and Water Jar, proves that she was old fashioned…really old fashioned. It turns out that the practice of presenting hostess gifts dates back to the ancient Greeks; in antiquity, though, it was the host—not the guest—who presented the gifts. This small fresco is an example of how the Romans played the hostess game and how this generosity was captured by ancient Roman artists.

House of the Stags, Herculaneum

Archaeologists discovered Still Life with Peaches and Water Jar in the House of the Stags in Herculaneum, once a wealthy, seaside town on the Bay of Naples just a few miles north of Pompeii. Like Pompeii, Herculaneum was destroyed by the eruption of nearby Mt. Vesuvius on August 24, 79 C.E. The House of the Stags, named after two sculptures of stags (or male deer) found in its peristyle garden, was among the fanciest houses in town, oriented to take full advantage of Herculaneum’s panoramic sea view. Archaeologists believe that the house was owned by the wealthy merchant Q. Granius Verus since his stamp was discovered on a loaf of bread, amazingly preserved by the volcanic ash, unearthed in the house. (Stamping bread was a common practice because Roman houses, unlike most modern houses, did not have private ovens. Ovens were dangerous and hot so most Romans took their bread out for baking after preparing the dough at home. You stamped your loaf so it would not get mixed up in the ovens or claimed by someone else.)

House of the Stags, Herculanum (photo: Cornell University)

We cannot be sure whether the family of the Granii were the original builders of the house (likely during the reign of the emperor Claudius, from 41-54 C.E.) but they seem likely to have undertaken a major renovation not long before Mt. Vesuvius erupted. In the years immediately preceding the destruction of Herculaneum, all 25 rooms in the House of the Stags were repaired and redecorated in the newest style of painting—the Fourth Style; only the old atrium, with its historic frescoes, remained untouched as a sign of the house’s historic importance. So, although the house survives today only as a ruin, when the Granii family woke up on that fateful morning in 79 C.E., they would have experienced a home resplendent with freshly painted walls and colorful mosaic floors, terrace fountains filling the spaces with the sound of trickling water, and gardens filling the house with wafts of sweet fragrance carried in by the sea air. It is too bad the day did not end as nicely.

Still Life with Peaches and Water Jar, detail of a Fourth Style wall painting from Herculaneum, Italy, c. 62-69 C.E., fresco, 14 x 13 1/2 inches (Archaeological Museum, Naples)

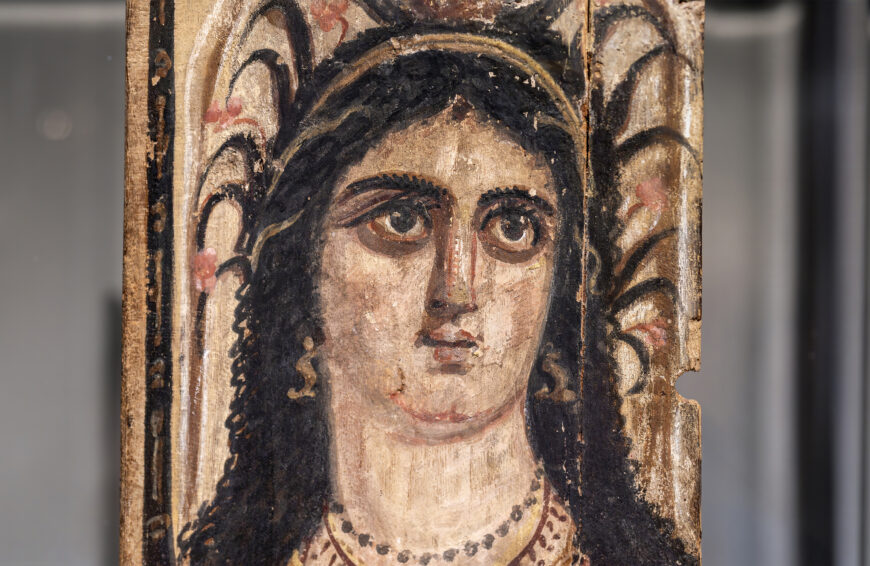

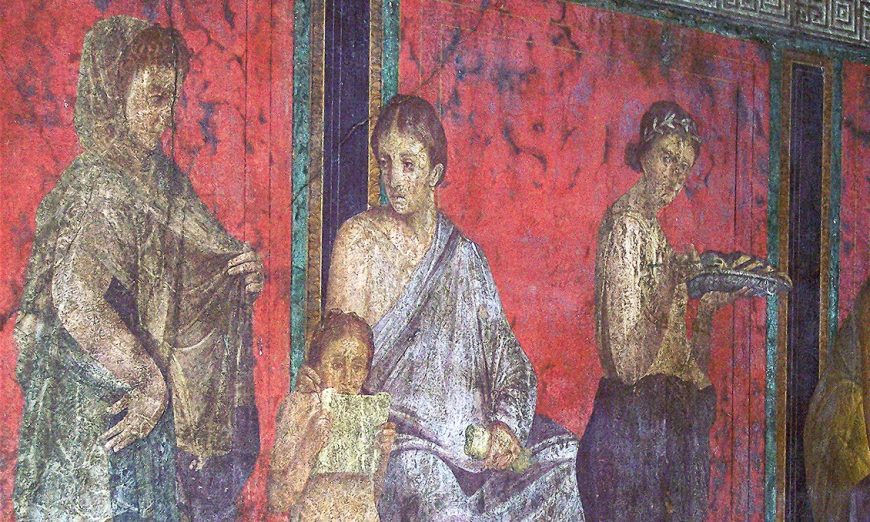

Still Life with Peaches and Water Jar was one small part of this house’s decorative scheme, not meant to be seen in isolation. It was part of a series of at least ten roughly-square still-life compositions, painted together in a row, sharing decorative borders. This series of paintings presents a variety of fruits, crustaceans, fish, fowl, meats, vegetables, and drinking vessels set against a neutral brown background, sometimes with a step, shelf or wall niche on which the artist arranged the display.

Still Life with Peaches and Water Jar features five unripe peaches (one only barely formed), their branch cascading off a shelf, and a glass jar of water in the foreground. One of the peaches has been pulled from the branch and bitten open, revealing a reddish pit and white flesh that contrast sharply against its yellow-green skin. The glass jar shows the artist’s ability to register two types of transparency at once: the clear glass vessel and the clear liquid that it contains. While the patron may have wanted the glass, among the most expensive luxuries in Roman Italy, included as a display of their wealth, the artist turned it into an opportunity to demonstrate his skill at depicting these visually complex attributes in perspective.

Xenia (hospitality)

Still Life with Peaches and Water Jar, like the small scenes that accompanied it, belongs to a category of still life paintings known as xenia, drawing on the Greek word for “guest-friendship” or hospitality. Xenia (hospitality) was shown to guests who were far from home by accommodating them and by presenting them with the means to be comfortable (a bed, food, a bath, etc.). This was not just a matter of being polite, but was considered a religious obligation for the Greeks—an idea preserved in both Homeric epic and mythology. The Greeks believed that Zeus Xenios, Zeus’s role as protector of guests, wandered in disguise with travelers, testing the capacity of hosts to be generous and tolerant. Although the devotion with which the Greeks pursued the quality of xenia was not matched by the Romans, the Romans nevertheless took pride in their ability to provide hospitality to guests, especially those whose social favor they wanted to earn (those who were more wealthy and socially important). Xenia, for the Romans, was more about the display of hospitality for appearance’s sake than it was a religious devotion.

Still Life with Hen (left), Still Life with Two Cuttlefish, a Silver Jug, Bird, Shells, Snails and Lobster (center), and Still-life with a Hare and Grapes (right), Fourth Style wall painting from Herculaneum, Italy, c. 62-69 C.E., fresco, 14 x 13 1/2 inches (Archaeological Museum, Naples)

The small xenia paintings at the House of the Stags are not unusual; many rich houses, especially houses and villas located along the coast where visitors from Rome might want to travel to escape the summer heat (or political turmoil), were outfitted with special guest quarters. Xenia paintings are frequently found in these rooms, announcing to these guests that they would be lavished with the finest foods and service wear while in the house. The ancient Roman architect Vitruvius suggested that the xenia include, in particular, “poultry, eggs, vegetables, and other country produce” as a way to highlight the experience of getting out of the city and into the countryside (de Architectura VI.7.4). The xenia at the House of the Stags, as Vitruvius might have liked, present fruits and fish (known as area specialties) along with the standard fare.

Still-Life with Chicken and Hare (left), Still Life with Partridge, Pomegranate and Apple (second from let), Still Life with Thrushes and Mushrooms (third from left), Still-Life with Partridges and Eels (far right), Fourth Style wall painting from Herculaneum, Italy, c. 62-69 C.E., fresco, 14 x 13 1/2 inches (Archaeological Museum, Naples)

Xenia paintings or mosaics also appear in more public areas of houses where clients (people who depend on the homeowner’s business) and less-wealthy visitors might see them. In these cases, the xenia spoke to the wealth of the family, and the level of generosity that they could afford to show to those lucky enough to be invited (even if the viewers did not belong to that chosen group). I suspect that my mother had a different idea when sending me with hostess gifts: more an apology for whatever trouble I might get in than a display of wealth and social importance. Still, her insistence that I present myself with hostess gift in hand demonstrates that showing our best and accommodating guests with grace has never gone out of style.