Related works of art

In the Ancient Mediterranean

Masks

Active in c. 5000 B.C.E.–350 C.E. around the World

In North Africa

Polykleitos, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer)

Greek original c. 450–440 B.C.E.; Roman copy before 79 C.E.

Italy

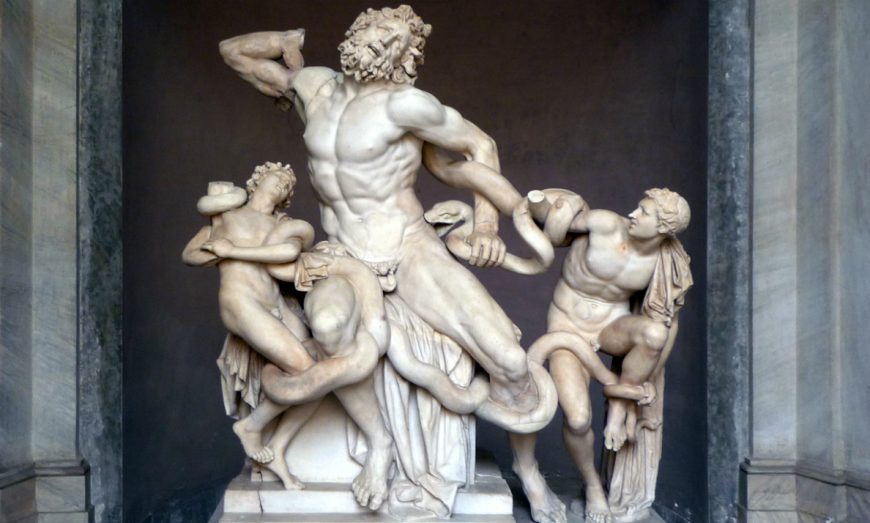

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons

early 1st century C.E.

Italy

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!