The Pantheon has one of the most perfect interior spaces ever constructed—and it’s been copied ever since.

The Pantheon, Rome, c. 125. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re standing in the piazza, the square in front of The Pantheon.

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:09] This is the best-preserved ancient Roman monument. Look at the sense of age, look at the weathering, look at the way in which its history is revealed through its surface.

[0:19] It’s been attacked, its original bronze fittings have been ripped off. Look at the numerous holes, for instance, in the pediment. They tell of all of the different purposes that this building has been put to.

[0:30] Originally a temple to the gods, then sanctified and made into a church. Now, of course, it’s also a major tourist attraction. This is a building that has had just a tremendously complex history, and you can see it all over its surface.

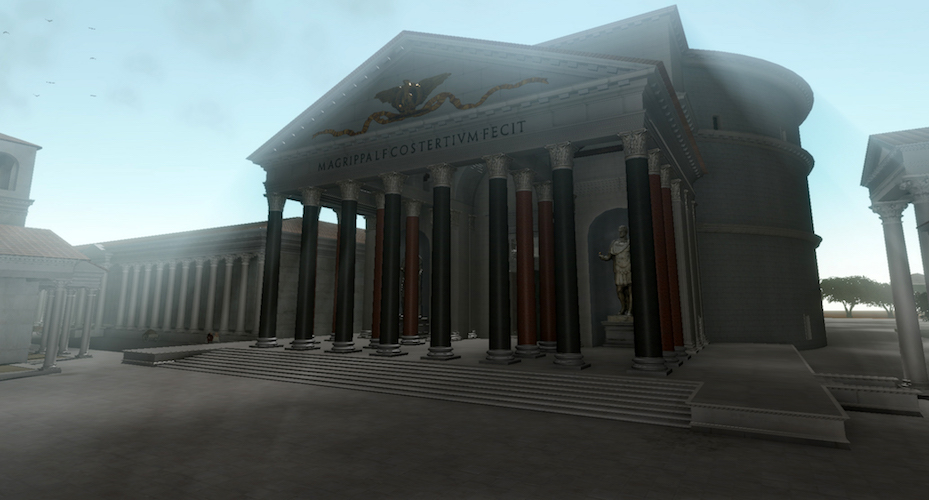

Dr. Harris: [0:43] We’re seeing it very differently than anyone in antiquity would have seen it.

Dr. Zucker: [0:47] In fact, we’re standing many feet higher than we would have been in the ancient world. Rome accumulated elevation from the debris of history. Once, you would have stepped up to the porch of the Pantheon. Now, we actually glide downhill.

Dr. Harris: [1:03] The space in front of the Pantheon was framed by a colonnade.

Dr. Zucker: [1:08] The colonnade and the other buildings that would have originally surrounded this building would have obscured the barrel on the side, and so that we would have only seen this very traditional temple front.

Dr. Harris: [1:19] Exactly. It would have been something very familiar. The surprise was what happened as you approached the threshold.

Dr. Zucker: [1:26] I have to tell you that I’m absolutely in love with those massive columns. They are supported by these enormous marble bases. They rise up unarticulated, without any fluting, and then end in these massive fragments of what were originally marble Corinthian capitals.

[1:44] These are monoliths. They’re single pieces of stone. Unlike Greek columns, they were not segmented. They were not cut. And they were imported from Egypt, which was symbolic of Rome’s power over most of the Mediterranean under the emperor Hadrian, who was responsible for the construction of this building.

[2:00] So let’s go in. Let’s go under the porch. Let’s go through those massive bronze doors. We just walked in under the strictly rectilinear porch. Then, the space opens up.

Dr. Harris: [2:11] Opens up into this vast circular space.

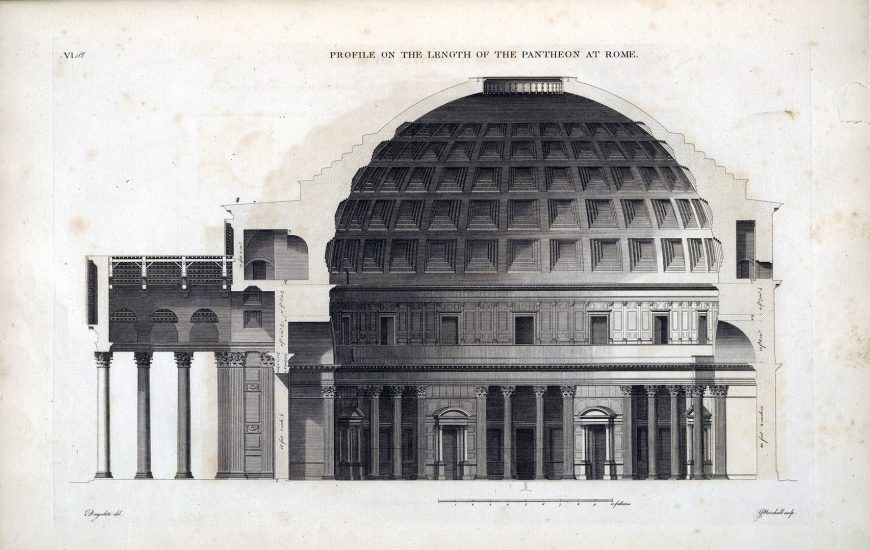

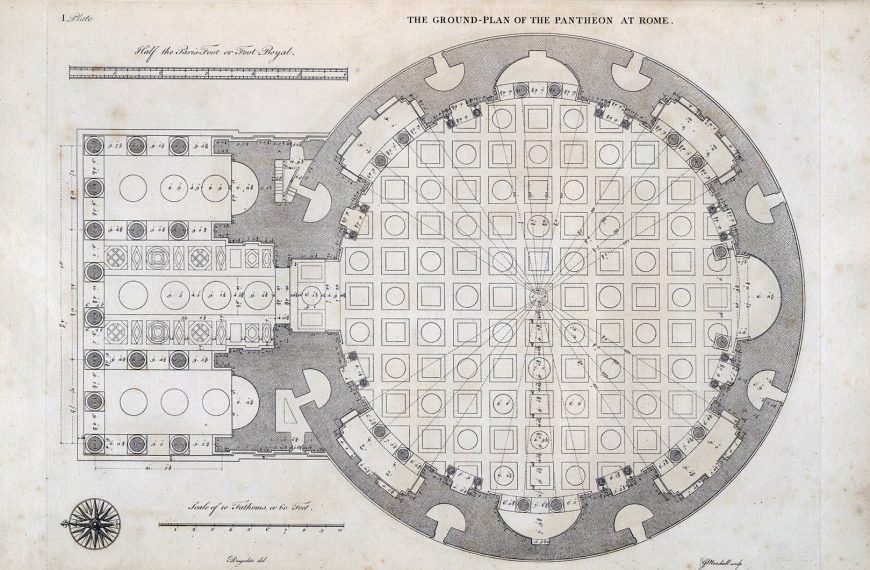

Dr. Zucker: [2:15] The width of the building and the height of the building completely fills my field of vision. It is, in a sense, an expression of the limits of my sight. Unlike a basilica, this is a radial building. That is to say that it has a central point, and radiates outward from that central point.

[2:33] But what’s fascinating about this building is it’s not a traditional radial structure in that the point would be on the floor. The central point, its focus, is midway between the floor and the ceiling and midway between its walls. It is large enough and geometrically perfect enough to accommodate a perfect sphere.

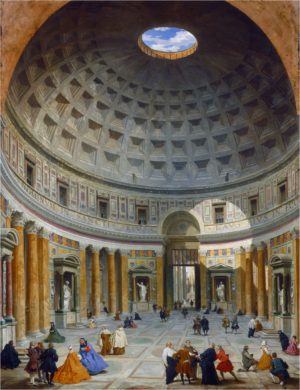

Dr. Harris: [2:54] And as soon as you walk in, you notice that there’s a kind of obsession with circles, with rectangles, with squares, with those kinds of perfect geometrical shapes.

Dr. Zucker: [3:06] This is a structure that is concerned with the ideal geometries, but it also locates our place within those geometries.

Dr. Harris: [3:14] But the experience of being in this space is anything but static.

Dr. Zucker: [3:18] No, it’s really dynamic, in fact. One of the causes of that is if we move our eye up the columns, you can see that they’re beautifully aligned with the frieze of false windows that are just above them, but then all of that does not align with the dome.

Dr. Harris: [3:33] That’s right. They don’t align with the coffers that we see in the dome. What that does is creates this feeling that the barrel that the dome rests on is independent from the dome and almost makes it feel as though the dome could rotate.

Dr. Zucker: [3:47] That complex visual relationship between the dome and the decorative structures in the barrel reminds us that this actual structural system here is dependent on concrete and not these decorative columns that we see on the interior.

Dr. Harris: [4:01] Exactly. There’s a thick barrel of concrete that supports the dome. Because a dome pushes down and out, Roman architects had to think about how to support the weight and pressure of the dome. And one of the things that’s doing that are the thick concrete walls of the barrel.

Dr. Zucker: [4:21] You know, the Romans had really perfected concrete, and this is one of the buildings that shows what was possible. This is shaping space because concrete could be continuous. It could be built upward continuously with wooden forms, which would then be removed and could then open this space up in a way that post-and-lintel architecture never could.

Dr. Harris: [4:39] So concrete could be laid onto a wooden support or mold and could be shaped in a way that you can’t do with post-and-lintel architecture.

Dr. Zucker: [4:49] Well, what it does is it allows for this vast, open, uninterrupted space. We walk into the space, and we feel freed. We are given a tremendous amount of freedom in terms of how we move and how we see through this space.

Dr. Harris: [5:00] Because of the Roman use of concrete, [there is] the idea that architecture could be something that shaped space and that could have a different kind of relationship to the viewer.

Dr. Zucker: [5:11] It is, even now in the 21st century, awesome. The Emperor Hadrian, under whose direction this building was constructed, apparently loved the building and loved to actually have visitors come to him here. One can imagine him even in the back apse opposite the entrance.

Dr. Harris: [5:27] The Pantheon originally contained sculptures of the gods, of the deified emperors, we think. It really was about the divine. It was about the earthly sphere meeting the heavenly sphere.

Dr. Zucker: [5:41] And also in some way about human perception. Look how rich the surface is.

Dr. Harris: [5:46] There would have been much more in antiquity, when the coffers probably had gilded rosettes. As we look at the drum, we see colored marble. We see purples and oranges and blues.

Dr. Zucker: [6:00] Remember, these marbles are taken from around the Roman Empire. So this is really an expression of Hadrian’s wealth and Hadrian’s power. This is the empire being able to reach across the globe to draw in these precious materials.

Dr. Harris: [6:15] Perhaps the most exciting part of this space is the oculus, because it almost seems to defy reason. How could there be a hole in the center of that dome? It doesn’t make sense.

Dr. Zucker: [6:27] Well, it’s the only light that comes into this space with the exception of some light wells in some of the recessed areas and of course the grille just above the door and the door itself. There is one great window. My students for years have asked, “Is there glass?” Of course, the answer is no. When it rains, the floor gets wet.

Dr. Harris: [6:46] The perfect circle of that oculus, the perfect circle of the dome.

Dr. Zucker: [6:53] The oculus is critical in the issues that you had raised before. This is a building that in some way is a reflection of the movement of the heavens.

[7:02] What happens is light moves into this space from the sun. It projects often a very sharp circle on the dome, and moves across the floor of the building as the sun moves across the sky, and then eventually creeps up the other side of the dome.

[7:19] And so this entire building functions, in some ways, almost like a sundial. It makes visible the movements of the heavens and makes them manifest here on earth. We’ve been talking about this building as a great monument of the ancient world, but it was admired and copied in the Renaissance.

[7:37] In fact, it’s perhaps the most influential building in architecture in the Renaissance and in the modern era. When you think about all of the different architects that have referenced this building…

[7:47] …I’m looking down at the floors and the geometry that you spoke of, the circles and the squares, and I’m thinking about the pavement in front of the Guggenheim Museum on Fifth Avenue in New York.

Dr. Harris: [7:56] Actually, once you know the Pantheon, you begin to see copies of it and pieces of it everywhere.

Dr. Zucker: [8:02] It’s true. The dome, especially, is perhaps the most copied element, especially with the oculus. You can see that, for instance, in the National Gallery in Washington. You can see it in almost every neoclassical building in Europe and North America. But before we leave, I’d love to go and pay homage to Raphael, who’s buried just over there.

[8:20] [music]

The eighth wonder of the ancient world

The Pantheon in Rome is a true architectural wonder. Described as the “sphinx of the Campus Martius”—referring to enigmas presented by its appearance and history, and to the location in Rome where it was built—to visit it today is to be almost transported back to the Roman Empire itself. The Roman Pantheon probably doesn’t make popular shortlists of the world’s architectural icons, but it should: it is one of the most imitated buildings in history. For a good example, look at the library Thomas Jefferson designed for the University of Virginia.

The Pantheon, Rome, c. 125 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While the Pantheon’s importance is undeniable, there is a lot that is unknown. With new evidence and fresh interpretations coming to light in recent years, questions once thought settled have been reopened. Most textbooks and websites confidently date the building to Emperor Hadrian’s reign and describe its purpose as a temple to all the gods (from the Greek, pan = all, theos = gods), but some scholars now argue that these details are wrong and that our knowledge of other aspects of the building’s origin, construction, and meaning is less certain than we had thought.

Whose Pantheon?—the problem of the inscription

Archaeologists and art historians value inscriptions on ancient monuments because these can provide information about patronage, dating, and purpose that is otherwise difficult to come by. In the case of the Pantheon, however, the inscription on the frieze—in raised bronze letters (modern replacements)—easily deceives, as it did for many centuries. It identifies, in abbreviated Latin, the Roman general and consul (the highest elected official of the Roman Republic) Marcus Agrippa as the patron: “M[arcus] Agrippa L[ucii] F[ilius] Co[n]s[ul] Tertium Fecit” (“Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, thrice Consul, built this”). The inscription was taken at face value until 1892, when a well-documented interpretation of stamped bricks found in and around the building showed that the Pantheon standing today was a rebuilding of an earlier structure, and that it was a product of Emperor Hadrian’s patronage, built between about 118 and 128. Thus, Agrippa could not have been the patron of the present building. Why, then, is his name so prominent?

The conventional understanding of the Pantheon

A traditional rectangular temple, first built by Agrippa

The conventional understanding of the Pantheon’s genesis, which held from 1892 until very recently, goes something like this. Agrippa built the original Pantheon in honor of his and Augustus’ military victory at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E.—one of the defining moments in the establishment of the Roman Empire (Augustus would go on to become the first Emperor of Rome). It was thought that Agrippa’s Pantheon had been small and conventional: a Greek-style temple, rectangular in plan. Written sources suggest the building was damaged by fire around 80 C.E. and restored to some unknown extent under the orders of Emperor Domitian.

The Pantheon, Rome, c. 125 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

When the building was more substantially damaged by fire again in 110 C.E., Emperor Trajan decided to rebuild it, but only partial groundwork was carried out before his death. Trajan’s successor, Hadrian—a great patron of architecture and revered as one of the most effective Roman emperors—conceived and possibly even designed the new building with the help of dedicated architects. It was to be a triumphant display of his will and beneficence. He was thought to have abandoned the idea of simply reconstructing Agrippa’s temple, deciding instead to create a much larger and more impressive structure. And, in an act of pious humility meant to put him in the favor of the gods and to honor his illustrious predecessors, Hadrian installed the false inscription attributing the new building to the long-dead Agrippa.

New evidence—Agrippa’s temple was not rectangular at all

Today, we know that many parts of this story are either unlikely or demonstrably false. It is now clear from archaeological studies that Agrippa’s original building was not a small rectangular temple, but contained the distinctive hallmarks of the current building: a portico with tall columns and pediment and a rotunda (circular hall) behind it, in similar dimensions to the current building.

Giovanni Paolo Panini, Interior of the Pantheon, Rome. c. 1734, oil on canvas, 128 x 99 cm (National Gallery of Art)

And the temple may be Trajan’s (not Hadrian’s)

More startling, a reconsideration of the evidence of the bricks used in the building’s construction—some of which were stamped with identifying marks that can be used to establish the date of manufacture—shows that almost all of them date from the 110s, during the time of Trajan. Instead of the great triumph of Hadrianic design, the Pantheon should more rightly be seen as the final architectural glory of Emperor Trajan’s reign: substantially designed and rebuilt beginning around 114, with some preparatory work on the building site perhaps starting right after the fire of 110, and finished under Hadrian sometime between 125 and 128.

Lise Hetland, the archaeologist who first made this argument in 2007 (building on an earlier attribution to Trajan by Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer), writes that the long-standing effort to make the physical evidence fit a dating entirely within Hadrian’s time shows “the illogicality of the sometimes almost surgically clear-cut presentation of Roman buildings according to the sequence of emperors.” The case of the Pantheon confirms a general art-historical lesson: style categories and historical periodizations (in other words, our understanding of the style of architecture during a particular emperor’s reign) should be seen as conveniences—subordinate to the priority of evidence.

What was it—a temple? A dynastic sanctuary?

It is now an open question whether the building was ever a temple to all the gods, as its traditional name has long suggested to interpreters. Pantheon, or Pantheum in Latin, was more of a nickname than a formal title. One of the major written sources about the building’s origin is the Roman History by Cassius Dio, a late second- to early third-century historian who was twice Roman consul. His account, written a century after the Pantheon was completed, must be taken skeptically. However, he provides important evidence about the building’s purpose. He wrote,

He [Agrippa] completed the building called the Pantheon. It has this name, perhaps because it received among the images which decorated it the statues of many gods, including Mars and Venus; but my own opinion of the name is that, because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens. Agrippa, for his part, wished to place a statue of Augustus there also and to bestow upon him the honor of having the structure named after him; but when Augustus wouldn’t accept either honor, he [Agrippa] placed in the temple itself a statue of the former [Julius] Caesar and in the ante-room statues of Augustus and himself. This was done not out of any rivalry or ambition on Agrippa’s part to make himself equal to Augustus, but from his hearty loyalty to him and his constant zeal for the public good.

A number of scholars have now suggested that the original Pantheon was not a temple in the usual sense of a god’s dwelling place. Instead, it may have been intended as a dynastic sanctuary, part of a ruler cult emerging around Augustus, with the original dedication being to Julius Caesar, the progenitor of the family line of Augustus and Agrippa and a revered ancestor who had been the first Roman deified by the Senate. Adding to the plausibility of this view is the fact that the site had sacred associations—tradition stating that it was the location of the apotheosis, or raising up to the heavens, of Romulus. Even more, the Pantheon was also aligned on axis, across a long stretch of open fields called the Campus Martius, with Augustus’ mausoleum, completed just a few years before the Pantheon. Agrippa’s building, then, was redolent with suggestions of the alliance of the gods and the rulers of Rome during a time when new religious ideas about ruler cults were taking shape.

Reconstruction by the Institute for Digital Media Arts Lab at Ball State University, interior of the Pantheon, Rome, c. 125 C.E. (Project Director: John Filwalk, Project Advisors: Dr. Robert Hannah and Dr. Bernard Frischer)

The dome and the divine authority of the emperors

By the fourth century C.E., when the historian Ammianus Marcellinus mentioned the Pantheon in his history of imperial Rome, statues of the Roman emperors occupied the rotunda’s niches. In Agrippa’s Pantheon, these spaces had been filled by statues of the gods. We also know that Hadrian held court in the Pantheon. Whatever its original purposes, the Pantheon by the time of Trajan and Hadrian was primarily associated with the power of the emperors and their divine authority.

Pantheon dome (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The symbolism of the great dome adds weight to this interpretation. The dome’s coffers (inset panels) are divided into 28 sections, equaling the number of large columns below. 28 is a “perfect number,” a whole number whose summed factors equal it (thus, 1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14 = 28). Only four perfect numbers were known in antiquity (6, 28, 496, and 8128) and they were sometimes held—for instance, by Pythagoras and his followers—to have mystical, religious meaning in connection with the cosmos. Additionally, the oculus (open window) at the top of the dome was the interior’s only source of direct light. The sunbeam streaming through the oculus traced an ever-changing daily path across the wall and floor of the rotunda. Perhaps, then, the sunbeam marked solar and lunar events, or simply time. The idea fits nicely with Dio’s understanding of the dome as the canopy of the heavens and, by extension, of the rotunda itself as a microcosm of the Roman world beneath the starry heavens, with the emperor presiding over it all, ensuring the right order of the world.

The Pantheon, Rome, c. 125 (photo: Alex Ranaldi, CC BY-SA 2.0)

How was it designed and built?

The Pantheon’s basic design is simple and powerful. A portico with free-standing columns is attached to a domed rotunda. In between, to help transition between the rectilinear portico and the round rotunda is an element generally described in English as the intermediate block. This piece is itself interesting for the fact that visible on its face above the portico’s pediment is another shallow pediment. This may be evidence that the portico was intended to be taller than it is (50 Roman feet instead of the actual 40 feet). Perhaps the taller columns, presumably ordered from a quarry in Egypt, never made it to the building site (for reasons unknown), necessitating the substitution of smaller columns, thus reducing the height of the portico.

Pantheon, Rome, c. 125 C.E. (photo: Darren Puttock, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Pantheon’s great interior spectacle—its enormous scale, the geometric clarity of the circle-in-square pavement pattern and the dome’s half-sphere, and the moving disc of light—is all the more breathtaking for the way one moves from the bustling square (piazza, in Italian) outside into the grandeur inside.

One approaches the Pantheon through the portico with its tall, monolithic Corinthian columns of Egyptian granite. Originally, the approach would have been framed and directed by the long walls of a courtyard or forecourt in front of the building, and a set of stairs, now submerged under the piazza, leading up to the portico. Walking beneath the giant columns, the outside light starts to dim. As you pass through the enormous portal with its bronze doors, you enter the rotunda, where your eyes are swept up toward the oculus.

Reconstruction by the Institute for Digital Media Arts Lab at Ball State University, exterior of the Pantheon, Rome, c. 125 C.E. (Project Director: John Filwalk, Project Advisors: Dr. Robert Hannah and Dr. Bernard Frischer)

The structure itself is an important example of advanced Roman engineering. Its walls are made from brick-faced concrete—an innovation widely used in Rome’s major buildings and infrastructure, such as aqueducts—and are lightened with relieving arches and vaults built into the wall mass. The concrete easily allowed for spaces to be carved out of the wall’s thickness—for instance, the alcoves around the rotunda’s perimeter and the large apse directly across from the entrance (where Hadrian would have sat to hold court). Further, the concrete of the dome is graded into six layers with a mixture of scoria, a low-density, lightweight volcanic rock, at the top. From top to bottom, the structure of the Pantheon was fine-tuned to be structurally efficient and to allow flexibility of design.

Who designed the Pantheon?

Pantheon, Rome, c. 125 C.E. (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

We do not know who designed the Pantheon, but Apollodorus of Damascus, Trajan’s favorite builder, is a likely candidate—or, perhaps, someone closely associated with Apollodorus. He had designed Trajan’s Forum and at least two other major projects in Rome, probably making him the person in the capital city with the deepest knowledge about complex architecture and engineering in the 110s. On that basis, and with some stylistic and design similarities between the Pantheon and his known projects, Apollodorus’ authorship of the building is a significant possibility.

When it was believed that Hadrian had fully overseen the Pantheon’s design, doubt was cast on the possibility of Apollodorus’ role because, according to Dio, Hadrian had banished and then executed the architect for having spoken ill of the emperor’s talents. Many historians now doubt Dio’s account. Although the evidence is circumstantial, a number of obstacles to Apollodorus’ authorship have been removed by the recent developments in our understanding of the Pantheon’s genesis. In the end, however, we cannot say for certain who designed the Pantheon.

Why Has It Survived?

We know very little about what happened to the Pantheon between the time of Emperor Constantine in the early fourth century and the early seventh century—a period when the city of Rome’s importance faded and the Roman Empire disintegrated. This was presumably the time when much of the Pantheon’s surroundings—the forecourt and all adjacent buildings—fell into serious disrepair and were demolished and replaced. How and why the Pantheon emerged from those difficult centuries is hard to say. The Liber Pontificalis—a medieval manuscript containing not-always-reliable biographies of the popes—tells us that in the 7th century Pope Boniface IV “asked the [Byzantine] emperor Phocas for the temple called the Pantheon, and in it he made the church of the ever-virgin Holy Mary and all the martyrs.” There is continuing debate about when the Christian consecration of the Pantheon happened; today, the balance of evidence points to May 13, 613. In later centuries, the building was known as Sanctae Mariae Rotundae (Saint Mary of the Rotunda). Whatever the precise date of its consecration, the fact that the Pantheon became a church—specifically, a station church, where the pope would hold special masses during Lent, the period leading up to Easter—meant that it was in continuous use, ensuring its survival.

Sanctae Mariae Rotundae (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Yet, like other ancient remains in Rome, the Pantheon was for centuries a source of materials for new buildings and other purposes—including the making of cannons and weapons. In addition to the loss of original finishings, sculpture, and all of its bronze elements, many other changes were made to the building from the fourth century to today. Among the most important: the three easternmost columns of the portico were replaced in the seventeenth century after having been damaged and braced by a brick wall centuries earlier; doors and steps leading down into the portico were erected after the grade of the surrounding piazza had risen over time; inside the rotunda, columns made from imperial red porphyry—a rare, expensive stone from Egypt—were replaced with granite versions; and roof tiles and other elements were periodically removed or replaced. Despite all the losses and alterations, and all the unanswered and difficult questions, the Pantheon is an unrivaled artifact of Roman antiquity.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”pantheon,”]