Great Pyramids of Giza with modern Cairo in the foreground: Khufu (c. 2600–550 B.C.E.), Khafre (c. 2575–2525 B.C.E.) and Menkaure (c. 2525–2475 B.C.E.) (photo: Tim Kelley, CC BY-ND 2.0)

Beginnings

The civilization of ancient Egypt obviously did not spring fully formed from the Nile mud; although the massive pyramids at Giza may appear to the uninitiated to have appeared out of nowhere, they were founded on thousands of years of cultural and technological development and experimentation. “Dynastic” Egypt—sometimes referred to as “Pharaonic” (after “pharaoh”, the Greek title of the Egyptian kings derived from the Egyptian title per aA, “Great House,” which was used from the New Kingdom on)—which was the time when the country was largely unified under a single ruler, begins around 3000 B.C.E.

The depiction of King Den smiting an enemy stands near the beginning of a 3,000 year tradition. King Den’s sandal label, 1st dynasty. c.3000 BCE, ivory, found at Abydos, Upper Egypt, 4.5 x 5.3 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

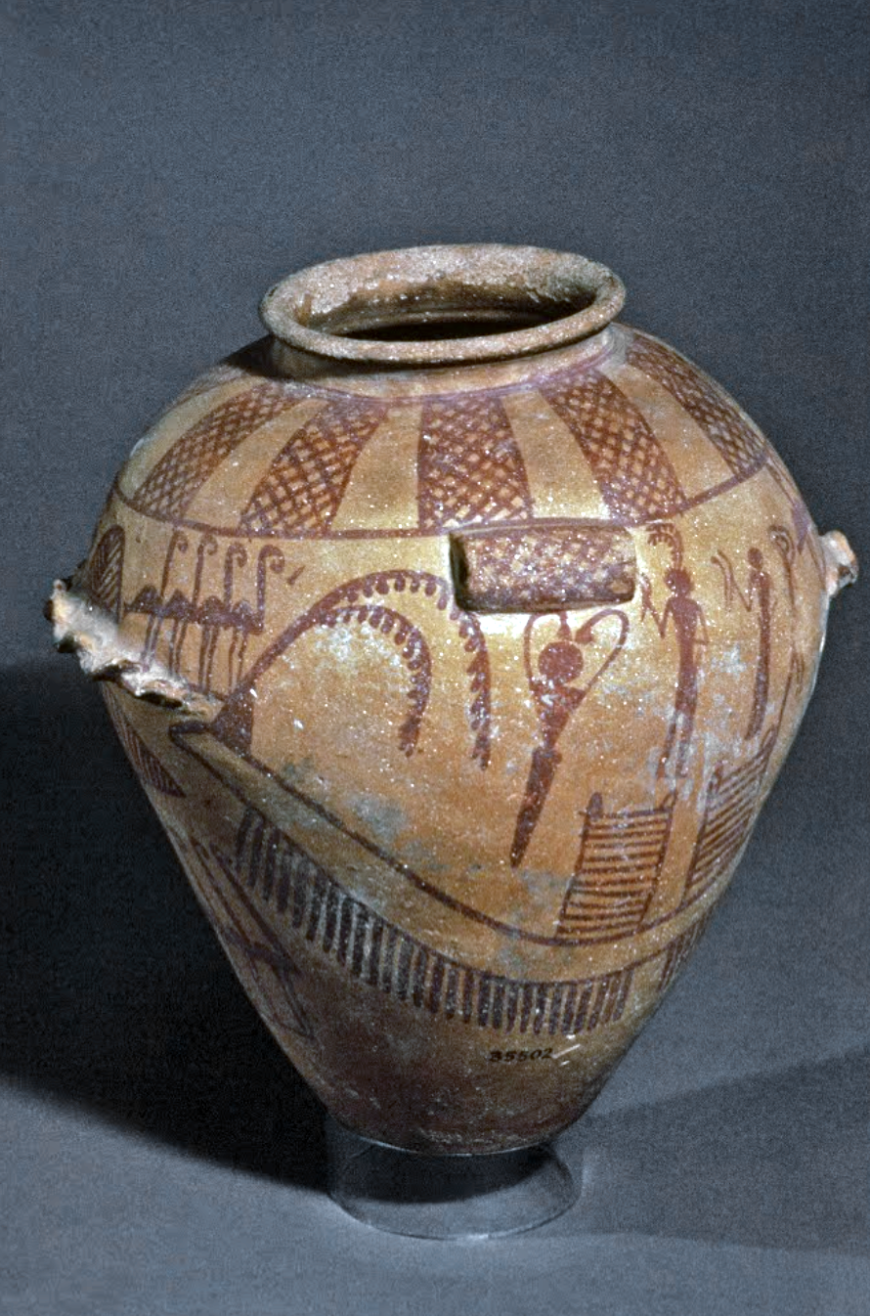

Decorated jar, c. 3500 B.C.E., predynastic period (Naqada II), pottery, found in a tomb in el-Amra, Egypt, 22.5 cm in diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The period before this, lasting from about 5,000 B.C.E. until the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under one ruler, is referred to as Predynastic by modern scholars. Prior to this were thriving Paleolithic and Neolithic groups, stretching back hundreds of thousands of years, descended from northward migrating homo erectus who settled along the Nile Valley. During the Predynastic period, ceramics, figurines, mace heads, and other artifacts such as slate palettes used for grinding pigments, begin to appear, as does imagery that will become iconic during the Pharaonic era and we can see the first hints of what is to come.

Dynasties, periods, and reigns

It is important to recognize that the dynastic divisions modern scholars use were not used by the ancients themselves. These divisions were created in the first chronological history of Egypt, written by an Egyptian priest named Manetho in the 3rd century B.C.E. Each of the 30 dynasties included a series of rulers usually related by family connections or the location of their seat of power. Egyptian history is also divided into larger chunks, known as “kingdoms” and “periods,” to distinguish times of strength and unity (kingdoms) from those of change, foreign rule, or disunity (periods).

Like many other ancient cultures, the Egyptians themselves referred to their history in relation to the ruler of the time. Years were recorded as the regnal dates of the ruling king, so that with each new reign, the numbers began anew. The usual dating format included the day of the month and season, along with the regnal year of the king—for example, “day 4 of the second month of the season peret in the third year of Khafre.” This ancient practice creates challenges for modern historians, making it difficult to determine exact dating for many events and reigns; this is the reason that different resource books on ancient Egypt may provide slightly different dates for the same object. Generally, dates are provided here as “circa,” (c.) or approximate, for this reason.

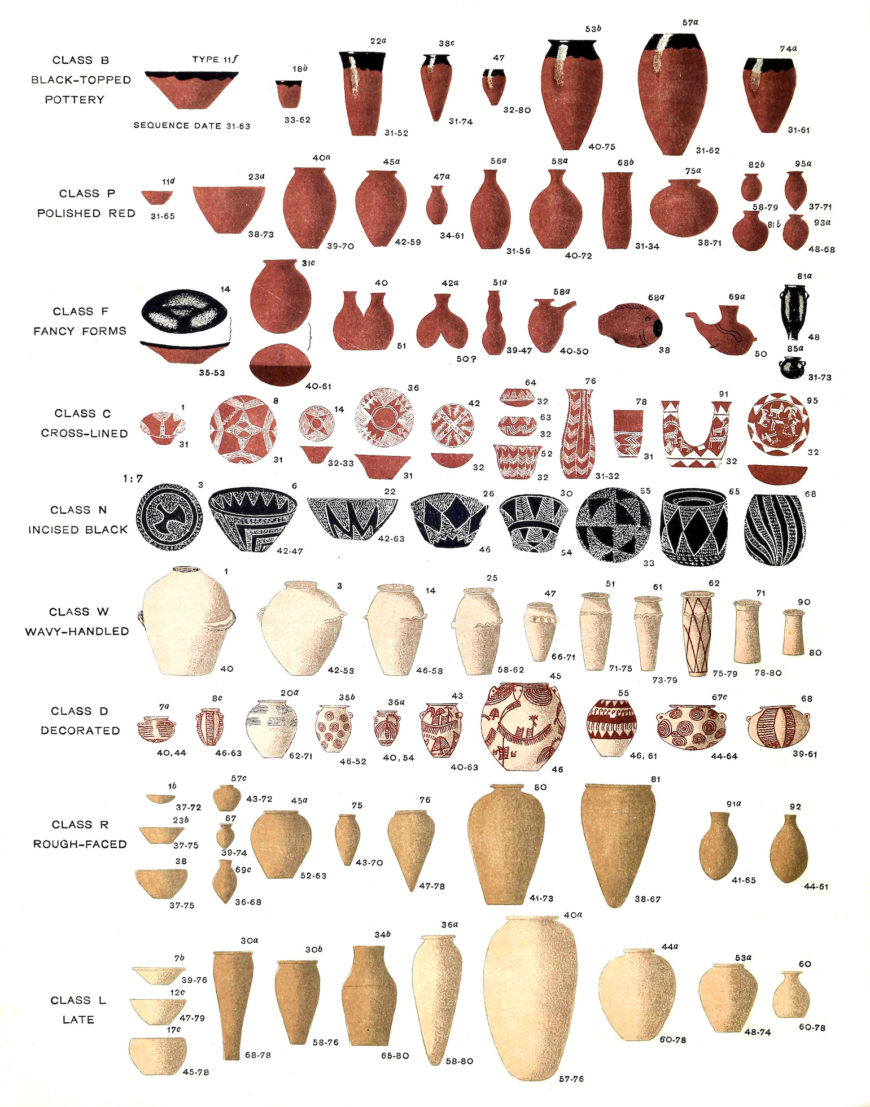

Evolution of Egyptian prehistoric pottery styles, from Naqada I to Naqada II and Naqada III (Adapted from Diospolis Parva: the cemeteries of Abadiyeh and Hu, 1898–99)

Determining chronology

We do have some absolute dates based on recorded astronomical observations, such as the rising of the star Sirius, that have greatly aided the pursuit of a reliable chronology. However, these set points are few and far between. Much of the chronology modern scholars use is built around those anchored, calendrical and astronomical events. This is combined with relative dating methods based on the sequence of recognized changes in artifact characteristics over time (especially ceramics) and scientific dating methods, such as radiocarbon dating and thermoluminescence, that can be applied to organic materials but offer a date range, rather than a date.

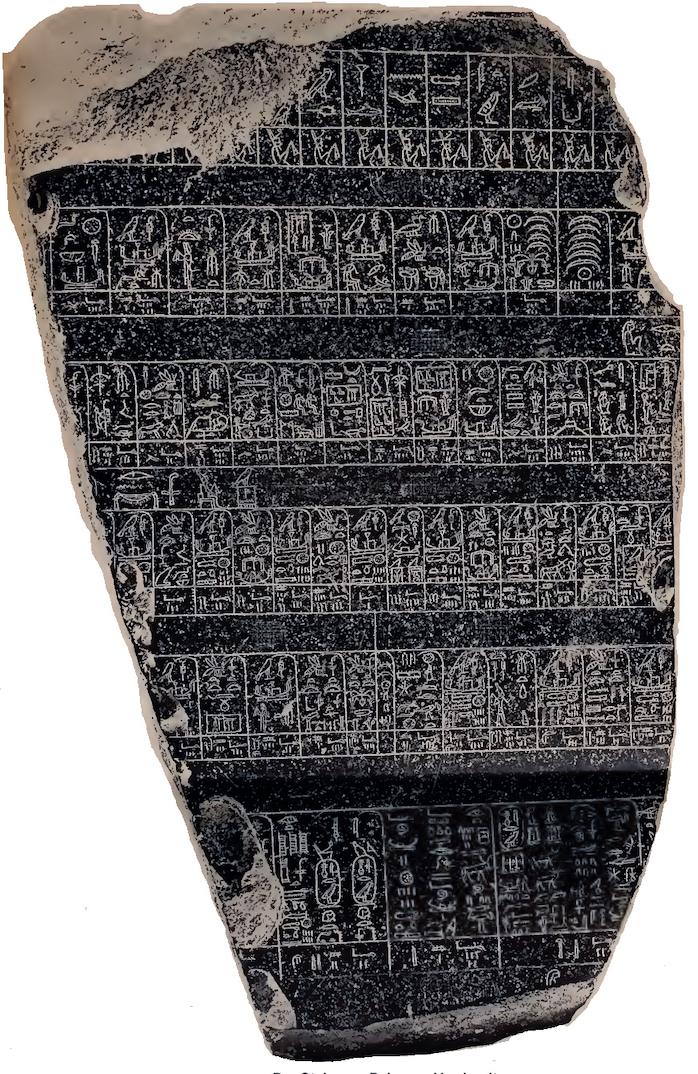

Palermo Stone, thought to have been created at the end of the 5th Dynasty (c. 2470 BCE) from p. 526 of Abhandlungen der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften aus dem Jahre… (Berlin: Verlag der Königlichen Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1901)

Manetho’s sources for his history are largely unknown. However, they would certainly have included annals, “day-books,” and ‘king-lists.’ These were records of the events that occurred during each king’s reign; unfortunately, few examples survive.

One of the most important surviving sources for the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom eras is a basalt stela fragment inscribed on both sides with royal annals stretching from the 5th Dynasty back to the mythical rulers of the Predynastic period. Known as the Palermo Stone, this slab was discovered in 1866 and records major cult ceremonies, building projects, details of Nile inundations, taxation reports, and warfare events.

A King List with the names of 76 rulers from ancient Egypt. Detail of the King List, 19th Dynasty c. 1279 B.C.E., from the Temple of Seti I, Abydos, Egypt (photo: Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0)

King-lists were also inscribed on the walls of some temples—one of the best-known being from the temple of Seti I at Abydos—and were written on papyri, although only one such example survives (the so-called Turin Canon from the thirteenth century B.C.E.).

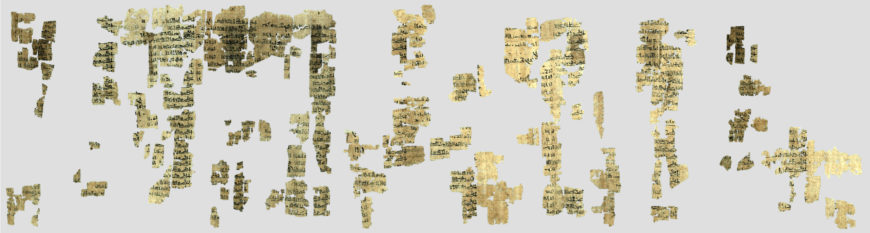

The Turin king list, or the Royal Canon of Turin, 1275–1200 B.C.E., papyrus (Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy ; photo: Pharoah.se, CC BY)

This valuable, but fragmentary, document records the list of kings and the length of their reigns stretching from the Second Intermediate Period back to the earliest kings from the 1st Dynasty. These lists were not necessarily focused on recording “history.” Instead, they were a form of ancestor worship, where the current ruler celebrated the consistency of kingship and presented their predecessors as a combination of the general, eternal concept of divine kingship and the individual, human ruler who held power at that specific moment.

| Period | Dates |

| Predynastic | c. 5000–3000 B.C.E. |

| Early Dynastic | c. 3000–2686 B.C.E. |

| Old Kingdom (the ‘pyramid age’) | c. 2686–2150 B.C.E. |

| First Intermediate Period | c. 2150–2030 B.C.E. |

| Middle Kingdom | c. 2030–1640 B.C.E. |

| Second Intermediate Period

(Northern Delta region ruled by Asiatics) |

c. 1640–1540 B.C.E. |

| New Kingdom | c. 1550–1070 B.C.E. |

| Third Intermediate Period | c. 1070–713 B.C.E. |

| Late Period

(a series of rulers from foreign dynasties, including Nubian, Libyan, and Persian rulers) |

c. 713–332 B.C.E. |

| Ptolemaic Period

(ruled by Greco-Romans) |

c. 332–30 B.C.E. |

| Roman Period | c. 30 B.C.E.–395 C.E. |

Periods and main characteristics

Egypt went through many waves of cultural development. Although its early development of beliefs, social structures, and imagery remained stable and iconic for millennia to come, later periods introduced new ideas that required adjustment. The Egyptians were extremely flexible because of their core stability, based on central beliefs that were set very early in their history. The following time periods, with their major events and unique characteristics, are the chapters in a story that stretches back to 5000 B.C.E.

Predynastic and Early Dynastic

Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period

Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period