Related works of art

In the Ancient Mediterranean

Masks

Active in c. 5000 B.C.E.–350 C.E. around the World

In North Africa

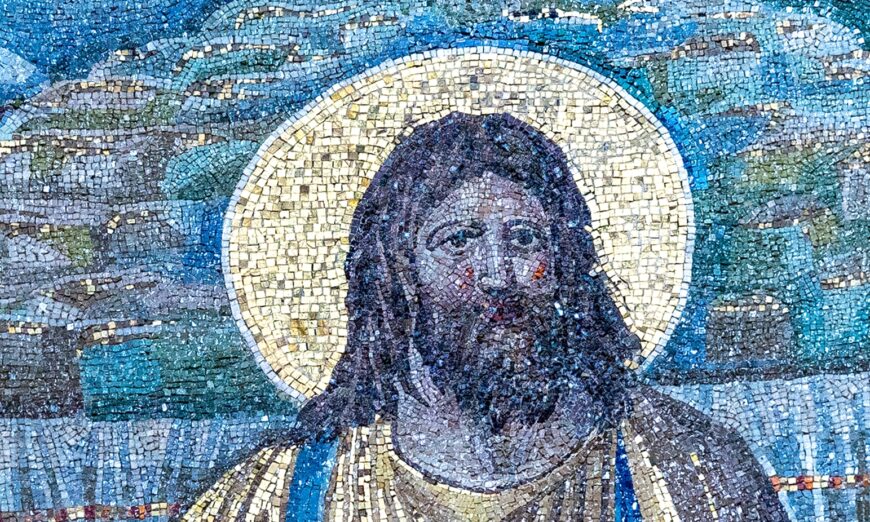

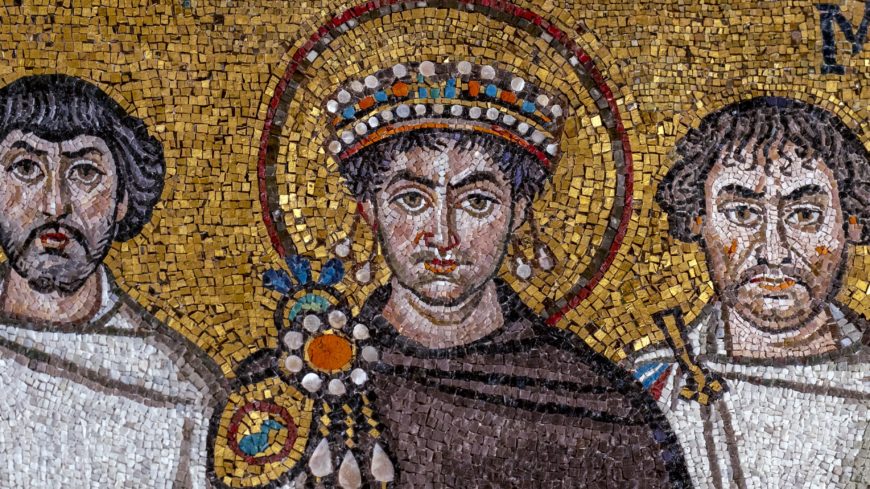

Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna (Italy)

basilica: c. 533–49, apse mosaic: 6th century, triumphal arch mosaics: likely c. 7th–12th centuries

Italy

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!