Alexander the Great (mounted figure at left) from The Alexander Sarcophagus, c. 312 B.C.E. (found in Sidon), Pentelic marble and polychromy, 195 x 318 x 167 cm (İstanbul Archaeological Museums)

The short and violent life of the Macedonian king Alexander the Great offers a useful case study in war’s repercussions for cultural heritage. As he fought his way through the Persian Empire in the late 4th century B.C.E., Alexander the Great famously destroyed monuments, such as the palace of Persepolis, an important political and administrative center in present-day Iran. At the same time, his conquest of the rich and powerful ancient kingdom of the Achaemenids also encouraged the creation of new works of art, for example, portraits of Alexander by the celebrated artists Lysippos and Apelles. And in his later years, Alexander became an increasingly significant rebuilder of monuments like the ziggurat of Babylon, better known as the Biblical Tower of Babel.

Alexander’s destruction, creation, and rebuilding of monuments illuminates ancient attitudes and practices toward cultural heritage in wartime. His actions suggest an ideal of protecting monuments during war, yet Alexander also used symbolic violence toward cultural heritage as a military and political strategy to demonstrate his absolute power and highlight the dangers of resistance. This has important repercussions for our understanding of ancient concepts of the protection of cultural heritage in wartime: an issue of critical importance in Alexander’s era, and one that remains highly relevant today.

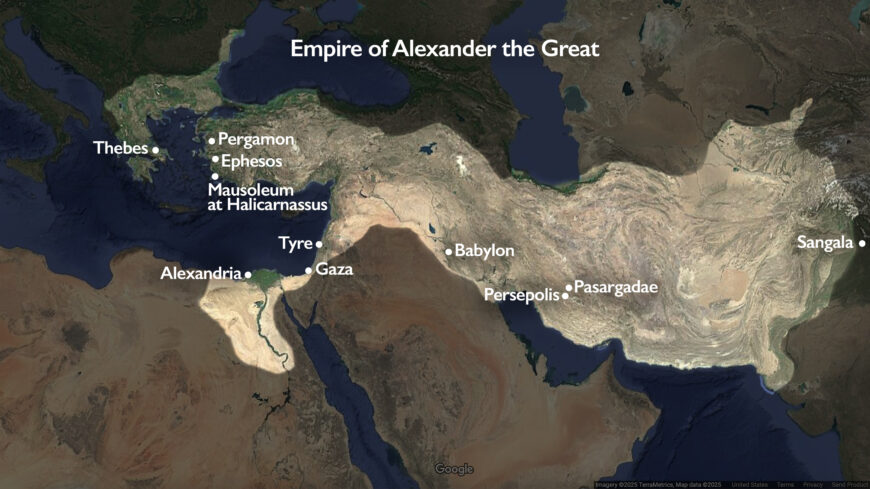

Empire of Alexander the Great with sites mentioned in the essay, except Cyropolis whose location has not been confirmed (underlying map © Google)

Alexander and the destruction of Persepolis

Alexander used destruction as a military tactic from the very beginning of his reign. Indeed, one of his first acts as monarch was to raze the rebellious city of Thebes in Greece (though he spared the temples of the gods and the house of the famous poet Pindar). Alexander continued to deploy this strategy throughout his conquests. Although he left most cities intact, he completely destroyed some, for instance, Tyre, Gaza, Cyropolis, and Sangala. Often, his city-destructions came at the end of a long, hard-fought siege and were retaliatory. Persepolis, however, was different.

Persepolis reconstruction (video still: ZDF/Terra X/interscience film/Faber Courtial, Gero von Boehm/Hassan Rashedi, Andreas Tiletzek, Jörg Courtial, CC BY-SA 4.0)

When Alexander arrived at Persepolis in present-day Iran in 330 B.C.E., the city’s inhabitants submitted without a fight. Nonetheless, they experienced an incredible act of violence: the burning down of their city, from the palaces on the terrace to the houses of the lower city. Alexander left a three-foot layer of ash covering the site, which was never substantially reinhabited. The question is why.

Audience hall columns, Persepolis, Iran, c. 500 B.C.E. (photo: Mauro Gambini, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Most ancient literary authors (and some modern scholars) suggest that the burning was inadvertent. Their story is that at a wine-infused banquet, the Athenian courtesan Thais came up with the idea, and the entire party lurched drunkenly after her, waving torches. The archaeology of the site, however, suggests otherwise.

Persepolis was thoroughly excavated in the 1930s, and its remains carefully published. From them, it is clear that Alexander cleaned out the treasury—a building that housed, on a conservative estimate, about 1,200 tons of silver—so that all that the excavators found was a total of 39 coins. He then had his soldiers prepare a fire, heaping up textiles in certain rooms, for example, to ensure that they would burn. And he targeted some politically important areas, such as the major ceremonial halls, while leaving others barely touched. Overall, the archaeological record shows that the burning was meticulously planned and carefully executed.

In the ancient literary sources, Alexander’s destruction of Persepolis is presented as gratifying the Greeks, who understood it as vengeance for the Persian king Xerxes’s invasion of Greece 150 years earlier. In the aftermath of that earlier invasion, the Greeks formulated what Thucydides 4.97 referred to as “the laws of the Greeks,” which were intended to govern the behavior of states in wartime. [1] As Adriaan Lanni has shown, these laws of war highlighted the preservation of monuments, particularly religious and funerary ones, as well as continuity in ritual practice. [2] They are significant as an early—and highly influential—formulation of a theory of cultural heritage protection. The destruction of Persepolis by Alexander, however, suggests the limits of the Greeks’ conception of cultural heritage, since what they condemned for their own sites clearly did not apply to Persian ones.

Alexander’s burning of Persepolis may have gratified the Greeks, but it was likely carried out in order to send a message to the Persians. Far more than the Greeks, they were the people whom Alexander still had to convince of his overwhelming power. After all, in 330 B.C.E., the Greeks were in no position to threaten the Macedonian king. By contrast, the Persians were still dangerous. Their Great King, Darius III, was still at large, and half their empire unconquered. So like Xerxes in his invasion of Greece, Alexander at Persepolis destroyed monuments in order to show his political and military might. The message was that he had conquered, and further resistance was futile.

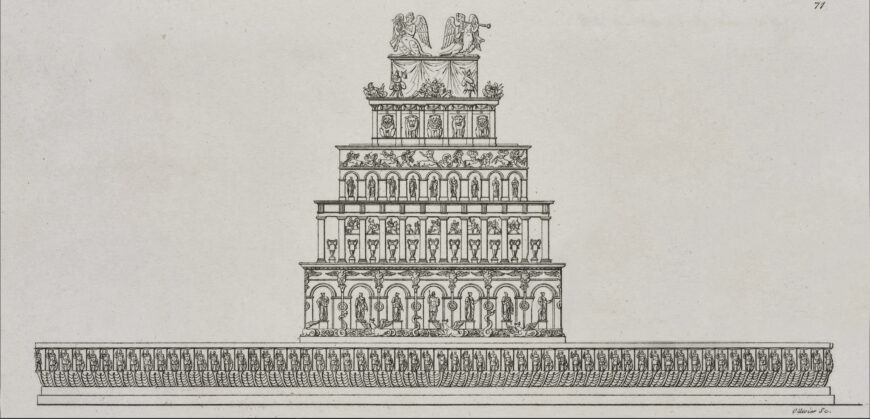

Pyre of Hephaistion, Babylon (speculative reconstruction), François-Charles-Hugues-Laurent Pouqueville, Grèce (Paris: Firmin Didot, 1835), plate 71

Alexander as creator: the pyre of Hephaistion

The destruction of cultural heritage in wartime is familiar, from Alexander’s era to our own. Less recognized is the tie between conquest and the creation of new monuments. As the preceding discussion of the Persepolis treasury suggests, through conquest Alexander gained the wealth necessary to become the ancient world’s most powerful artistic patron. He used that wealth selectively and strategically to create a new visual language of imperial power. Although Alexander himself died young, this visual language was then emulated by his successors, and proved highly influential. While scholars have focused on Alexander’s creation of the Hellenistic royal portrait as a genre, his activities as an artistic patron went well beyond portraits. The king also commissioned “history paintings” (which do not survive) by the artists Philoxenos of Eretria and Helen of Egypt, as well as a now-lost war memorial to the twenty-five officers who died at the battle of the Granikos, with life-size bronze statues of all of them.

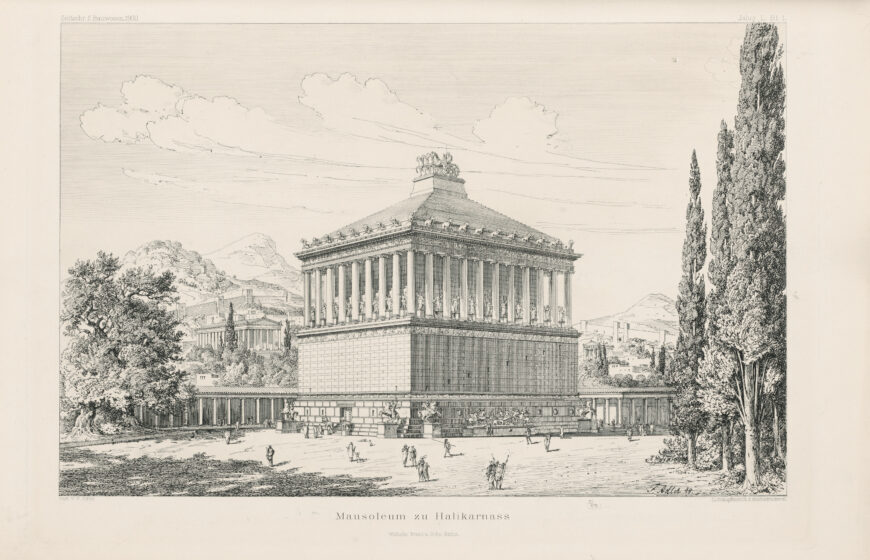

Still, the quintessential Hellenistic monument—the one that best highlights what is revolutionary about the period’s art—is not one of these but instead a commission designed to be ephemeral: the funerary pyre of Hephaistion, Alexander’s closest friend and likely lover, which was set up in Babylon in 323 B.C.E. Burned down like Persepolis in a grandiose conflagration at Hephaistion’s funeral, it highlights the performative and even destructive character of Alexander’s artistic innovations. The pyre of Hephaistion, described in Diodorus Siculus (17.115.1–5) and with some archaeological material remaining, was paradigmatic of Hellenistic art in many ways. [3] It was, to begin with, created by a famous architect: Deinokrates, responsible as well for the urban plan of Alexandria in Egypt. It was also massive, featuring seven levels like the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos—a famous recent monument in a city Alexander knew well, since he spent several months besieging it. And the pyre was expensive, with a reported cost of 10,000 talents.

Friedrich Adler, Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (south view), engraving on paper, 27.6 x 43 cm, Atlas zur Zeitschrift für Bauwesen (Ministry of Public Works, volume 50, 1900)

Most striking, however, was the pyre’s iconography. It featured up-to-date imagery, for instance, ships, a hunt scene, and weapons of both the Macedonian victors and Persian victims in Alexander’s wars. At the same time, the pyre also contained mythological images, for instance a battle of men and centaurs like the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos, as well as hollow statues of sirens inside of which real people stood to sing. And finally, it included traditional Ancient West Asian imagery such as lines of lions like those of the Ishtar Gate in Babylon. In this way, the pyre combined material that was often kept separate in earlier art: mythological and historical, West Asian, and Macedonian. Given that it was designed by a Greek architect, but likely executed by a far more heterogeneous group of sculptors and craftsmen from the cosmopolitan city of Babylon, this mix of imagery is not surprising.

Alexander’s activities as a creator of monuments combine different artistic traditions. While rarely acknowledged, this is actually very important for understanding the trajectory and range of Hellenistic art. Scholars of the period have often focused on works produced in Greece itself and the western coast of Turkey: the Venus de Milo, the Altar of Zeus from Pergamon, etc. But a full accounting of what Hellenistic art was like would pay more attention to the vast territories conquered by Alexander—everywhere from Albania to Pakistan—and the visually hybrid works they produced. Such an accounting would allow for a clearer appreciation of what is new and significant about Hellenistic art.

Alexander’s restoration of the tomb of Cyrus

Alexander’s restoration of monuments is the least recognized aspect of his interactions with cultural heritage. It is, however, very significant, showing his concern for not just Greek but also Ancient West Asian works. It also suggests his awareness of the danger war poses to cultural heritage and his attempts at mitigation.

Historical accounts of Alexander’s activities show an extraordinary and ecumenical range of restoration. He offered, for example, to restore the burned-down Greek Temple of Artemis at Ephesos, although the Ephesians refused. Alexander was more successful in persuading the Babylonians to allow him to assist with their Ziggurat of Marduk. Both Greek literary sources and Babylonian cuneiform tablets attest to his efforts, although he did not live long enough to complete the renovation.

Tomb of Cyrus the Great, c. 529 B.C.E. (Achaemenid), Pasargadae, Iran (photo: Bernd81, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The most revealing and significant of Alexander’s restoration projects, however, came at Pasargadae: first capital of Persian empire and the site for the coronation of every Persian king. There, the tomb of Cyrus, founder of the dynasty, was especially important. When Alexander visited in 324 B.C.E., he found it ransacked. Cyrus’s rich clothes, tapestries, jewelry, and swords were all gone; his couch with feet of gold and golden sarcophagus were broken; his body was dumped on the ground. Although Alexander himself was not directly responsible for it, he had created the conditions of chaos and lawlessness that allowed such plundering—a microcosm of what happened throughout the empire in the aftermath of the Macedonian conquest. In response, Alexander had one of his Greek officers restore the tomb. The officer’s memoir described proudly how he put the Great King’s body back in its sarcophagus, repaired the tomb’s furnishings, and ordered new garments, tapestries, weapons, and jewels.

Art historians have paid little attention, but the tomb of Cyrus is one of the rare preserved monuments that we can associate directly with Alexander the Great. It is significant not because he transformed it—he did not—but instead because he made a substantive effort to restore it to its original condition. His action suggests that in his last years, Alexander was moving toward an appreciation of monuments that did not simply prioritize the Greek. It indicates how far he had come since the destruction of Persepolis, applauded by the Greeks despite their “laws of war” regarding cultural heritage protection. With the tomb of Cyrus, we see Alexander instead seeking to restore the cultural heritage of those he conquered. It was a show of power over his expanded territories, but also an acknowledgement of his responsibility for his empire, and for the destruction he had wrought. At a time when we still struggle with wartime damage to monuments, his actions are worth noting.