View of the south side of the Arch at Orange, facing town, with the road out of town visible through the archway. Modern traffic is diverted around the arch. Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E. stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (photo: Jean-Louis Zimmermann, CC BY-SA 2.0)

When you walk up to the ancient arch at Orange, France, you realize what makes it memorable. Even the column bases rise higher than your head, and you have to walk through and around the three archways to experience the sculpted imagery. Celtic symbols, Greek battles, and Roman cityscapes all vie for your attention. This is one of the largest monuments to survive from the ancient Roman empire, and its design reveals how cultural traditions were lost, combined, and transformed in ancient France.

Map showing the location of Marseille, Orange, Saintes, Paris, Rome, and Pula (underlying map © Google)

An architectural tradition

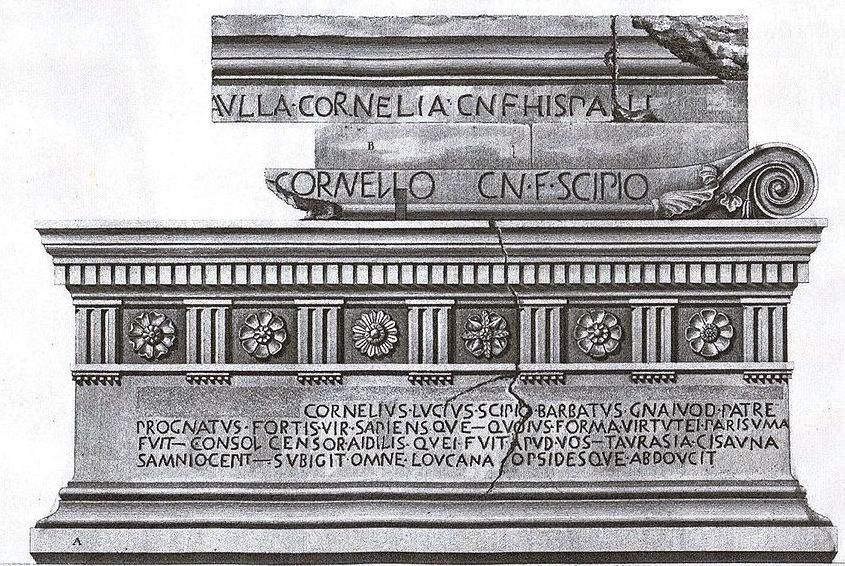

Arch monuments are more often associated with the city of Rome in Italy, where they emerged around 200 B.C.E. The Roman Senate and People (Senatus Populusque Romanus, SPQR) officially dedicated dozens of arch monuments there, including the now famous ones honoring emperors Titus, Septimius Severus, and Constantine. Yet residents of the Roman empire could dedicate arch monuments anywhere and to anyone.

Left: This arch was dedicated by Salvia Postuma in honor of her husband and his relatives (CIL V, 50). There are personified victories sculpted in the spandrels on either side of the archway. Arch monument (west side), Pula, Croatia, c. 20–10 B.C.E., stone, 10.62 x 8 x 2.3 m (photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0); right: This arch was dedicated by Gaius Julius Rufus to the emperor Tiberius and his heirs (CIL XIII, 1036). It was taken apart and rebuilt on higher ground in the 1840s. Arch monument (west side), Saintes, France, c. 18–19 C.E., stone, 14.7 x 15.9 x 3.9 m (photo: Johan Allard, CC BY-SA 4.0)

At Pula, Croatia, for instance, a woman named Salvia Postuma honored her husband with a single-bay arch, and in Saintes, France, and a Celtic aristocrat named Gaius Julius Rufus honored the emperor and his heirs with a double-bay arch. These and hundreds of other arch monuments from the Roman empire demonstrate great variety in their dimensions, designs, and who dedicated them.

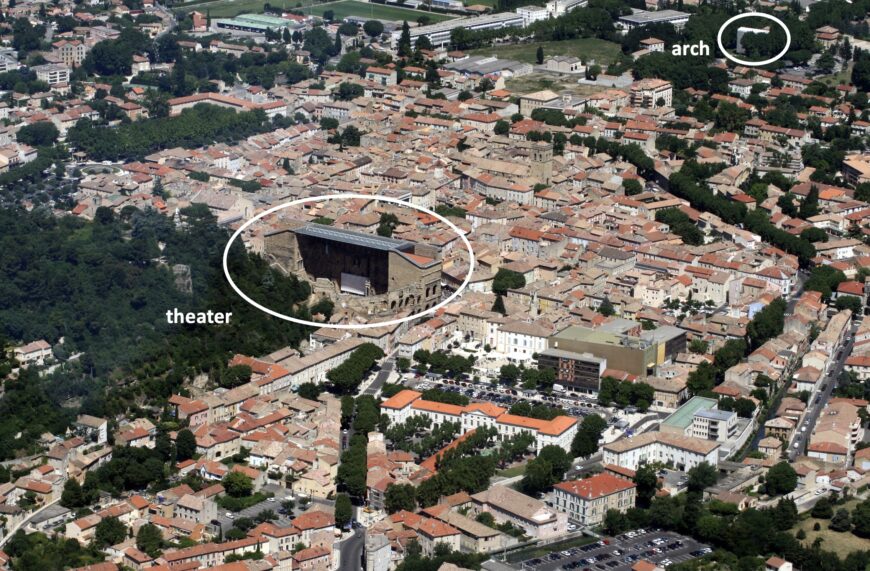

Aerial view of Orange in 2009, with the ancient theater shown in the center of town and the arch shown at the edge of town while under scaffolding for cleaning (photo: Jean-Louis Zimmermann, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Welcome to Orange

Rising just over 19 meters (62 feet), the triple-bay arch at Orange has always been hard to miss. Although its date is debated, most specialists now think it was constructed in the 20s B.C.E., a period of urban expansion when arch monuments were new to the region. [1] The arch stood just to the north of town and spanned a major road called the Via Agrippa. For people departing and arriving, the monument showed where to expect a transition between cityscape and countryside. Tall and traversable, arch monuments were often positioned to help people navigate busy cityscapes and road networks.

Northeast corner of the Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E., stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (annotated, original photo: Suwannee.payne, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Maximal design

Most ancient arch monuments—like the ones at Pula and Saintes—had minimalist designs with few sculpted scenes. The arch at Orange reveals a maximal approach to decoration. There are not just garlands, religious vessels, and mythical creatures, but also battle scenes, boats, weaponry, and captives. The sculptures combine a remarkable range of artistic traditions in a region with a long history of cultural exchange.

East side of the Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E., stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (annotated, original photo: jean-louis Zimmermann, CC BY 2.0)

Celts and Greeks before Romans

Rome’s imperial system bound together dozens of different peoples, and the residents of southern France included both Celts (called Gauls in Latin) and Greek colonists. Rome’s leaders pursued a clever expansion strategy here and elsewhere. They formed alliances with communities just beyond their empire’s border and then invaded when those allies needed help or when conflicts destabilized borderlands. Rome claimed southern France in the 120s B.C.E. after its ally the Greek colony Marseille asked for help. Rome claimed the rest of France in the 50s B.C.E. after a migrating Celtic people caused territorial conflicts among other Celtic peoples. Once established, Rome’s imperial system prioritized integration over annihilation. Soldiers could acquire Roman citizenship through military service, and local leaders governed through elected magistracies and city councils.

Triton (merman) holding part of a boat (detail), east end of the Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E., stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (photo: Marianne Casamance, CC BY-SA 3.0)

A mixed community

In the 30s B.C.E., Orange became a colony for soldiers retiring from Rome’s army. At that point, southern France had been part of the Roman empire for about a hundred years. Inscriptions show that people with Italic, Celtic, and Greek names lived here. Precisely why this mixed colonial community set up one of the empire’s most prominent monuments—with one of the most eclectic sculptural designs—is an enduring mystery.

North side of the Arch at Orange showing the small holes in the architrave where the bronze letters of the dedicatory inscription were attached. Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E., stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (annotated, original photo: Christophe Finot, CC-by-SA 3.0)

A mysterious dedication

The arch originally had a dedicatory inscription above its central archway on the north side (the side facing visitors arriving from other towns). All that survives now are small holes where the bronze letters were attached. Based on similarly sized inscriptions elsewhere, the city council likely voted and paid for the monument and dedicated it to the reigning emperor or his heirs. [2] We do not know who designed the arch at Orange, because ancient architects rarely signed their work.

View of the northeast corner of the Arch at Orange showing the design’s continuous architectural framework. Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E., stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (photo: Marianne Casamance, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Lines and lighting

If you trace the design of the arch at Orange, you find a geometric framework organizing the abundant sculptures. Vertical columns and horizontal cornices create a grid. Archways add half-circles, and triangular pediments introduce dynamic diagonal lines. The sculpted scenes make the surface appear richly textured, and the carved details are gradually revealed and concealed by shifting angles of sunlight throughout the day. Colorful paint may have further enlivened this design, but no pigments survive.

Room M, Villa of P. Fannius Synistor, Boscoreale, c. 50–40 B.C.E. (late Republican Rome), fresco, 265.4 x 334 x 583.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Trendy architectural illusions

If you take a closer look at the architectural design, you realize that the arch at Orange is a building that depicts other buildings. The pediments and columns adorning all four sides are more decorative than structural, and they evoke popular places like temples and columned walkways (porticoes). Art depicting architecture was at the height of its popularity when this arch was built, and architectural schemes survive in wall paintings, terracotta plaques, glass cups, and other media. The monument’s architectural illusions are more extensive than on any other arch in the empire, and they were the trendiest element of its complex design.

South side of the Arch at Orange showing an unidentified woman on a projecting part of the attic. The holes surrounding the sculpture show where metal attachments were once nailed. Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E., stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (photo: Marianne Casamance, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Gleaming metalwork

We should imagine an even more elaborate design than the one that we see. There were likely statues on top, where the attic takes the shape of projecting pedestals. There were also hundreds of metal attachments, to judge from the many small holes dotting the monument’s surface. Some of these bronze attachments surrounded the sculptures high on the arch’s south side, where they would have added a dramatic flourish by reflecting sunlight.

Victory personified from Arles, c. 27 B.C.E.–14 C.E., gilt bronze, 76 x 36.5 x 7.9 cm, excavated from the Rhône River in 2007 (Musée Départmental Arles Antique, Arles; photo: Finoskov, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Other attachments might have resembled the victory personified that was recently excavated at nearby Arles (ancient Arelate). On arch monuments honoring military leaders—like the one at Pula, illustrated above—victories often fly toward the main archway as if to crown victors moving through the monument.

South side of the Arch at Orange in 2007 (left) and 2014 (right), before and after conservators cleaned pollution from the surface and filled in the larger attachment holes around the central archway and pediment (photos: Kimberly Cassibry (left) and Carole Raddato (right), both CC BY-SA)

Some of the larger attachment larger holes were recently filled to protect the surface from further decay, but are still visible in earlier images. No other arch monument in the Roman empire had so much metalwork attached to its surface.

Top: North side of the Arch at Orange showing a battle scene in the Hellenistic Baroque style. Because there were never metal attachments added around this scene (in contrast to the one on the south side), scholars have wondered if the arch was left unfinished (photo: Tony Bowden, CC BY-SA 2.0); bottom: East end of the Arch at Orange with the battle frieze in the Classical style, .5 m high. This band of sculpture continues around the monument, except in the damaged areas and above the inscription on the north side (photo: Marianne Casamance, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Battle styles and victory propaganda

The design also featured international artistic styles. The battle scenes at the top have the dense and dynamic compositions typical of the Hellenistic Baroque style, most famously used on the Great Altar at Pergamon. In the encircling frieze, combatants have the looser spacing and more balanced poses typical of the Classical style, most famously used on the Parthenon in Athens. At the time, both Pergamon (in what is today Turkey) and Athens (in what is today Greece) were under Roman rule, and their associated styles remained popular for new art. It was unusual, however, to see both styles on the same monument.

South side of the Arch at Orange showing bearded men fighting in the Hellenistic Baroque battle scene. The deeply carved outlines made the sculptures easier to see from the ground. This photo was taken up close while the monument was being cleaned. Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E., stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (photo: Jean-Louis Zimmermann, CC BY-SA 2.0)

On the arch, these generic scenes do not visualize how historical battles actually occurred, but instead allude to forces of order (who prevail) and chaos (who lose). Some of the losing soldiers have messy beards and wear trousers, two features commonly used to depict men from regions that had not yet yielded to Roman rule. These battle scenes were pure propaganda: the people who fought Rome’s expansion did not see themselves as agents of chaos in need of order.

East end of the Arch at Orange showing trophy sculptures with Celtic boar standards and carnykes (annotated detail), Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E., stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

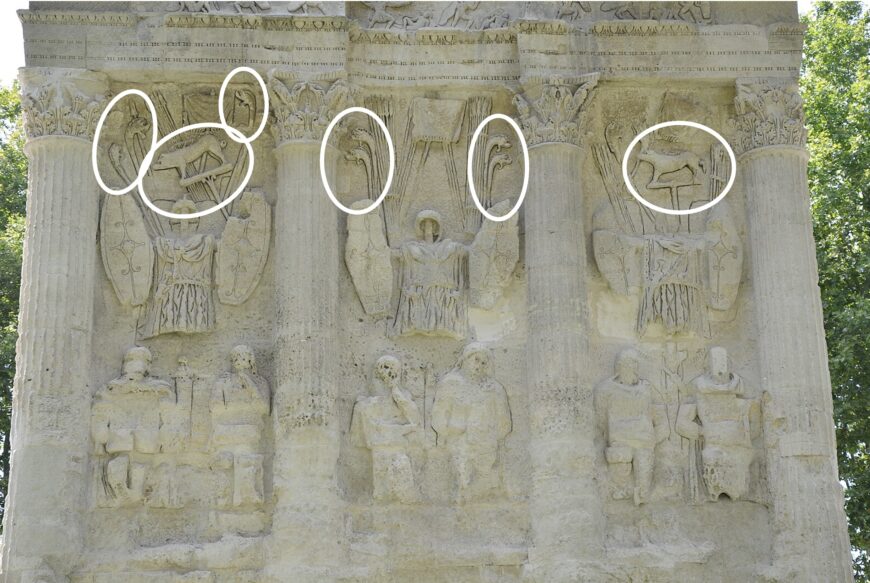

Spoils of war and Celtic cultural heritage

Captured symbols of Celtic power appear on all sides of the arch. The sculptures depicting seized military standards (troop emblems, here shaped like boars) and carnykes (tall animal-headed war trumpets) express the beautiful craftsmanship of these objects. As Celtic peoples stopped producing and using the traditional military art of their ancestors, the arch at Orange became one place where detailed images remained visible in daily life.

Ancient carnyx (tall, animal-headed war trumpet), bronze, 1st century B.C.E., excavated at Tintignac, France, in 2004 (photo: Claude Valette, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On the arch’s smaller sides, the boar standards and carnykes appear in trophy motifs, where the seized weaponry is displayed on tall supports and defeated peoples are posed beneath. On the main façades, the same symbols appear in the piles of seized weaponry (called spolia or spoils) sculpted above the smaller archways. Trophy and spolia motifs had their origins in Greek victory art, but were popular around the Roman empire too.

Weaponry sculptures with Celtic boar standards and carnykes (detail). Also visible are the battle frieze (above), the Corinthian columns (to either side), and the archivolt (archway) with egg-and-dart molding and a garland. Arch at Orange, France, 20s B.C.E., stone, 19.21 x 19.57 x 8.4 m (photo: Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0)

To depict boar standards and carnykes as spoils of war was to celebrate victories over the Celtic peoples who valued them. Yet these peoples—who once inhabited much of ancient Europe—did not see themselves as a unified group, and their perceptions of power changed as their soldiers joined the Roman army and secured citizenship for themselves and their descendants. There is no evidence to tell us how members of the colony’s mixed community identified with the monument’s sculptures over time.

UNESCO and imperial legacies

The arch at Orange is now protected by a UNESCO World Heritage listing, as are other ancient sites that took shape in Celtic lands under Roman rule—Hadrian’s Wall and Bath in England are good examples. The Roman empire is particularly well-represented on the UNESCO World Heritage list because many nations are motivated to preserve their Roman-era remains. Yet when a site’s links to the city of Rome are emphasized, as they typically are to justify recognition, ties to the empire’s diverse peoples and their connected cultures often fade from view.

The ancient arch at Orange shows us how a monument invented in the city of Rome was reimagined in ancient France. Its abundant sculptures combined classic Greek battle scenes, architectural illusions popular in Italy, and captured symbols of Celtic power. None of the monuments in the city of Rome looked exactly like this. Instead, this arch’s innovative design preserves the cultural connections of a contact zone where Celtic war art once made a strong impression.

View of the monument (northeast corner) when it was part of a tower. Étienne Martellange, View of the Roman Triumphal Arch at Orange, c. 1600, black chalk with pen, brown ink, and gray wash, 38.2 x 52.6 cm (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford)

Backstory

The people of Orange never tore down their ancient arch monument, though they did later transform it into a fortified tower. By the 1720s, that tower had been dismantled, and artists depicted the monument in ruins. A major intervention took place in 1822, when the architect Auguste Caristie fully reconstructed the arch’s ruined sections. Soon after, in 1840, the arch at Orange appeared on a groundbreaking list of protected heritage sites in France, along with seven other ancient arch monuments. [3] These fragile structures were valued for their histories, yet they had little influence on the design of later French monuments, such as Napoleon’s now famous arches in Paris.

Left: East side of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, Paris, France, 1806–31, stone, 14.6 x 19.5 x 6.7 m (photo: Sebastian Bergmann, CC BY-SA 2.0); right: south side of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel showing relief sculpture of armor below an allegorical scene depicting the Peace of Pressburg (photo: Thesupermat, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Napoleon’s monuments, like the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in Paris, honored the French empire’s army, and they were officially called triumphal arches, a term rarely used in antiquity. Their designs were inspired by the ancient arches built for the emperors Titus, Septimius Severus, and Constantine in Rome. One key detail from the arch at Orange was copied and updated: sculptures of piles of weaponry appear around the smaller archways of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel. As France’s leaders presented their expanding nation as a new Roman empire in the 18th and 19th centuries, preserving ancient arch monuments and building new ones reinforced this historical connection.