Shrine to Mithras (Mithraeum), c. 240 C.E., painted plaster, 162.5 x 206.4 cm, today installed in the Yale University Art Gallery

On the frontier between east and west

The ancient site now known as Dura-Europos (in what is today Syria) was not a key site in antiquity if we only rely on preserved historical narratives in which it barely features. Rather, its importance is in its vast archaeological record, a record which we are still studying a century after excavations began. That record tells a complex picture about a diverse town which negotiated its place on the frontier between east and west, ending only when the site became a battlefield on which Roman and Sasanian armies clashed.

Dura-Europos has been destroyed many times. A Roman rampart built to protect the city in the third century C.E. failed, but luckily for us preserved beneath it are the extensive religious wall paintings for which the site is best known. In the twenty-first century, it has been destroyed again in the crossfire of the Syrian conflict, and by targeted antiquities looting. The extensive excavations conducted at the site over the past century nonetheless allow an important window into this ancient frontier town where a range of languages from Greek and Latin to Palmyrene Aramaic, Hebrew, and Safaitic, were written, and an even broader range of deities were worshipped.

The site sits above the Euphrates river in Syria, a strategic location that was likely the reason for its founding in about 300 B.C.E. during the Hellenistic period. That initial settlement is not well known archaeologically, but was based on and around a citadel at the eastern edge of the site.

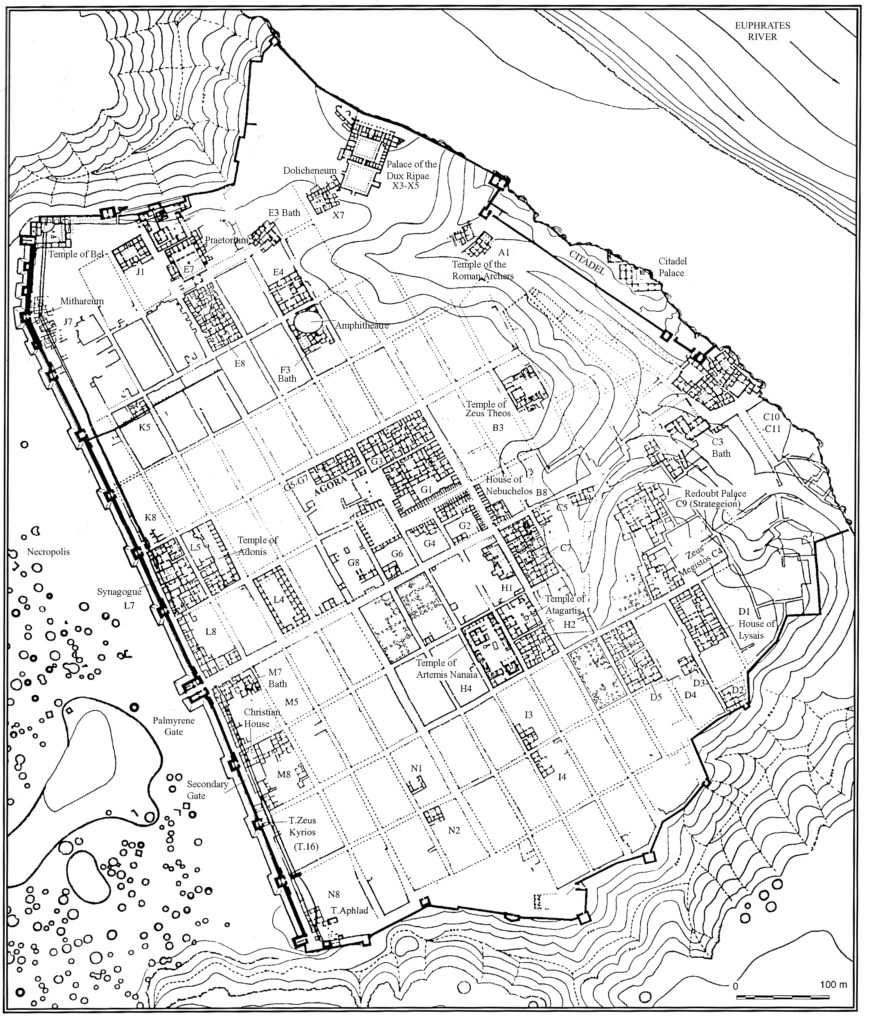

Site plan showing orthogonal (grid-planned) city blocks filling c. 52 hectares (128.5 acres) within the city walls and defended by steep cliffs on three sides. Plan by A. H. Detweiler, modified by J. Baird. Original used by kind permission of Yale University Art Gallery

Eventually it grew, with orthogonal (grid-planned) city blocks within the city walls and defended by steep cliffs on three sides. The long fortification wall on the western side of the site was pierced by a central gate dubbed the “Palmyrene Gate’”(indicated in the plan above) by its excavators, as it faced the steppe across which was Syria’s famous oasis city of Palmyra. A necropolis, consisting largely of chamber tombs, was preserved outside those city walls to the west.

Early history under the Arsacids

For most of its history, from the late second/early first century B.C.E. until the late second century C.E., the site was held by the Arsacids (an eastern dynasty known to the Romans as the Parthians), but their power was indirect: it was wielded at Dura by a small number of local families. One family (the head of which held the title of strategos or general of the city), was the Lysiads—known not only from inscriptions but also from a large house associated with them that filled an entire city block (also indicated by block D1, near the right edge, in the plan above).

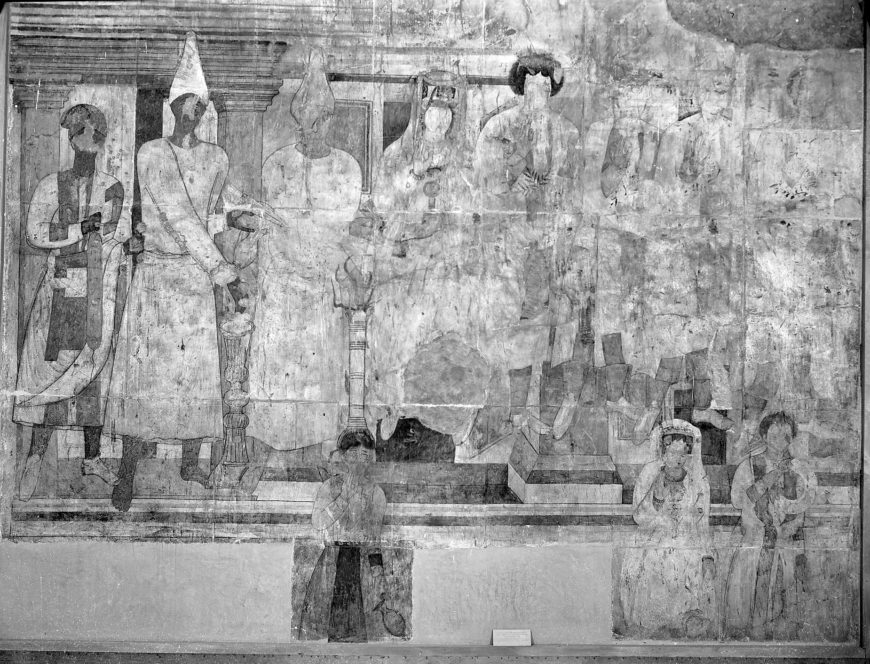

Painting of Conon and his family performing a sacrifice, installed for display in the Syrian National Museum in Damascus, from the ‘Temple of Bel’ in northwest corner of the city (Yale Dura Archive Dam157)

Painting of Conon and his family performing a sacrifice, installed for display in the Syrian National Museum in Damascus. From the ‘Temple of Bel’ in northwest corner of the city

Elite families are also depicted in paintings, such as that of Conon and his family performing a sacrifice, which was found in a temple in the northwest corner of the city known as the ‘Temple of Bel’. Under the Arsacids, the city was a regional capital where legal matters were handled, judging from civic records preserved on parchments at the site. The site also lay on important long-distance trade routes, which was perhaps the reason people from Palmyra were present at the site from at least the first century B.C.E.

The precise dates Dura was held by different powers are not known, despite having a great number of texts from the site, including inscriptions, parchments, and papyri which were recovered during excavations. This is in part because Dura was in a frontier zone of constantly shifting power.

Roman triumphal arch with Latin inscription found outside the city walls, reconstruction by Detweiler in 1937 (Yale Dura Archive Y594)

Greek Inscription recording renovation of religious building by Alexander, known also as Ammaios (Inscription no. 868, Photo Y466, Yale University Art Gallery)

The Romans

We know from inscriptions that the Romans under Trajan held the site, briefly, in the early second century, from a triumphal arch built outside the city (above), and from another inscription which belonged to a religious building (left). That inscription (dated c. 117 C.E.) records the restoration of a temple by a man known both by the Semitic name Ammaios and the Greek name Alexander, who held a position of priest. This restoration was needed because the doors of the building (presumably, made or decorated with something precious) had been “taken away by the Romans”, who had since departed the city. This practice of double-naming in which people from Dura have both Semitic and Greek names hints at the hybridity of the site, a characteristic that is also seen in its material culture.

Head of deity wearing a headdress, possibly Zeus Megistos, from the Temple of Zeus Megistos. Yale University Art Gallery 1938.5316

An earthquake in 160 C.E., recorded in a local inscription, is thought to have been the impetus for the building (and re-building) of a number of religious buildings in the second century. The sanctuaries are conventionally known by names assigned by the excavators (such as the ‘Temple of Zeus Megistos’ or ‘The Temple of Artemis’) but most of them preserved evidence for a range of deities. For instance, within the Temple of Zeus Megistos are found not only Zeus Megistos, but also the Palmyrene god Arsu and a nude hero, usually identified as Heracles or Nergal, who was popular at the site.

Left: Relief of the god Arsu, with Palmyrene Aramaic inscription reading “Arsu, the camel rider, ‘Ogâ, the sculptor made it for the life of his son”. Traces of black paint survive around the eyes, and the inscription was painted in red; the god is armed with a lance and shield. From the Temple of Zeus Megistos, Block C4 on the plan above(Yale University Art Gallery 1938.5311); right: Nude hero wrestling a lion, probably Heracles wrestling the Nemean lion. From the Temple of Zeus Megistos, Block C4 on the plan above (Yale University Art Gallery 1938.5302)

Interior of west end of Mithraeum during excavation, showing reliefs and paintings (Yale University Art Gallery, Dura-Europos Archive)

Within those sanctuaries were also found religious paintings, preserved best along the western side of the city beneath the Roman embankment, and sometimes “cult reliefs” (small inscribed reliefs dedicated to particular gods). Two such reliefs were found in the Mithraeum, a building dedicated to the god Mithras, whose cult spread widely during the Roman period, mostly among the military, particularly in the third century (see left and the top of this essay). People from Palmyra worshipped in the Mithraeum, and in other religious buildings at Dura, as we know from inscriptions which record their names and the names of their gods, often in Palmyrene Aramaic.

Late in the second century or early in the third, a Roman military garrison was installed within the city walls, taking over many existing buildings and constructing new ones on the north side of the site, including a Roman military palace, an amphitheatre, a principia (headquarters building), and baths. While this marked a major change at the site, and would have displaced many inhabitants, members of the Roman military did adapt to some local practices.

Painting from the ‘Temple of Bel’ of Julius Terentius and his men performing a sacrifice (Yale University Art Gallery, 1934.386)

For instance, a painting of the Roman tribune (cohort commander) Julius Terentius and his men performing a sacrifice was installed in the Temple of Bel, joining the earlier one of Conon and his family, and from a document on papyrus (such as divorce document P. Dura 32, 254 C.E.) we know of Roman soldiers who married local women.

View of the western wall of a model of the Dura-Europos Synagogue with narrative wall paintings and Torah shrine as it may have appeared between 244 and 256 C.E. The paintings are based on photographs taken prior to 1967. The model was created by Displaycraft in 1972 (collection of Yeshiva University Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The earliest Christian house-church and a Jewish synagogue

The installation of the Roman garrison did not mark the end of life at the site, and some religious buildings were built and renovated during this period, including the Jewish synagogue with its extensive wall paintings (from the 2nd century), and a house which was adapted by the Christian community for use as a meeting place and baptistery (from the first half of the 3rd century), in which were preserved Christian paintings. This is the oldest preserved Christian house-church that is archaeologically known.

Latin inscription, painted on a wooden plaque, found in the Palmyrene gate, reading “To Septimius Lysias Strategos of Dura and the wife of the one mentioned above, Nathis, and their children Lysianius and Mecannaea, and Apollophanes and Thiridates, From the Beneficiarii and Decurions of the Cohort,” 3rd century C.E. (Yale University Art Gallery, 1929.370)

Elite families also held on to power, at least for a while, and negotiated their place under Roman rule by, for example, taking Roman names in addition to their other names and titles. In one inscription painted on a wooden plaque found at the Palmyrene gate, it notes one “Septimius Lysias Strategos of Dura,” with Septimius as the added Roman name. Formal inscriptions, usually carved in stone rather than painted on wood, are found in Greek, Latin, and Palmyrene Aramaic throughout the site.

Graffito from Strategion palace (Block C9 on the plan above) of mounted lancer and deer (Yale Dura Archive D200)

On walls throughout Dura, hundreds of graffiti were found, ranging from simple scratched images of camel caravans to elaborate urban landscapes, and preserving lists, receipts, calendars, horoscopes, and many names. These occurred on fortifications in busy parts of the city like the Palmyrene gate but also house walls and within religious buildings and were not illicit markings in the way we think of graffiti today.

Satellite imagery before (top) and after episodes of heavy looting (bottom), leaving the surface of the site covered in round depressions resembling a moonscape (retrieved from Google Earth)

The end of Dura-Europos as an urban settlement

The end of the site as an urban settlement and military garrison came c. 256 C.E. when the Sasanians captured it, after a siege, known from the preserved remains of a siege ramp, mines, and countermines, as well as military equipment. The walls of the site still stood though, and indeed were still standing in the 20th century for it to be discovered. Those same walls stand today, but since the start of the Syrian conflict (2011–present) the site has become, again, a place of conflict. The most notable aspect of this is the systematic looting of the site for antiquities which could be trafficked onto the antiquities market. Satellite photos show the extent of the damage, with the surface of the site covered in the holes made by looters.

Despite the looting at the site, the new destruction has not erased the past of this ancient Syrian city, and much remains to be learned. The extensive excavations tell a story not only of successive empires but also of the resilience of daily life during those times, for instance in the continuity of the mudbrick and plaster courtyard houses which characterized the site. With the extensive archaeological archive which survives from the excavations of the 1920s and 30s we can continue to investigate this multicultural and polyglot ancient site.