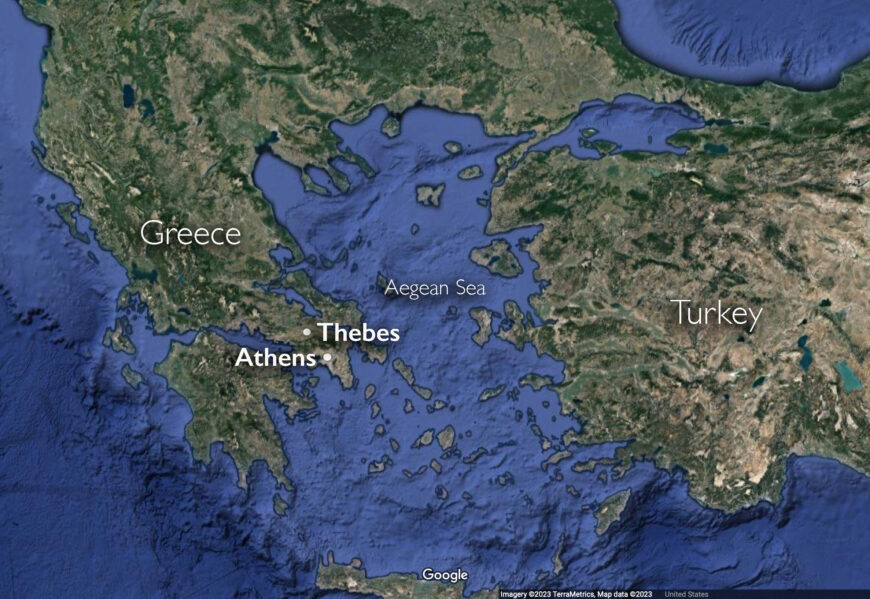

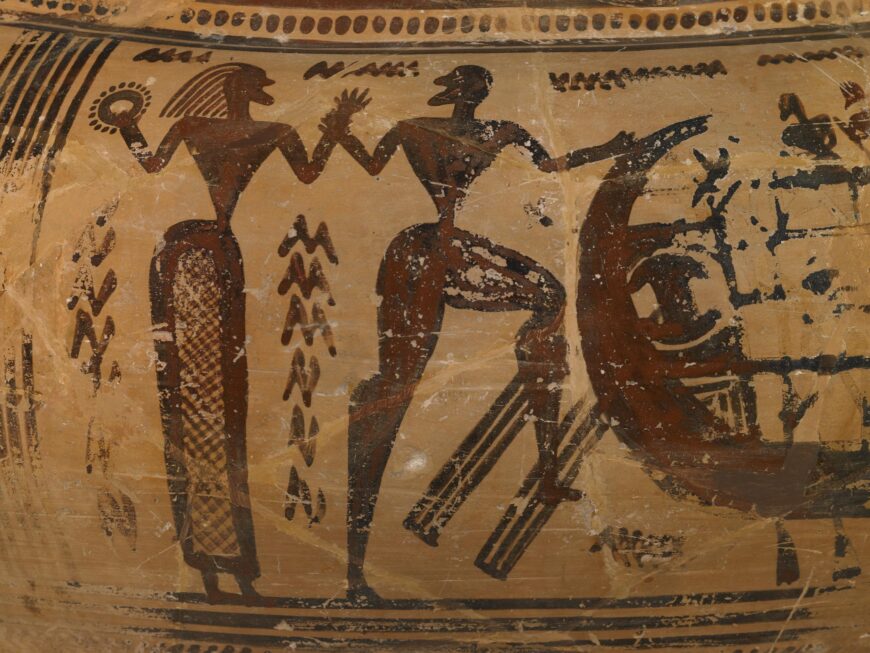

Krater with ship scene, c. 735 B.C.E., ceramic, 30.5 x 38 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

On the side of an ancient vessel, 40 rowers use their oars to propel a huge ship forwards. To the left, a couple approaches the boat. The man grabs the woman (who is marked as female by her long hair and patterned skirt) by the wrist as he steps towards the ship. [1] He looks back towards her as she holds up her hands, carrying a circular, wreath-like object in one. The general actions taking place in the scene are clear: a man and a woman are about to board a large boat that is manned by many rowers. But the lack of specificity in the depiction makes it difficult to determine who exactly these figures are. Since they have no facial features, their expressions are unreadable. Since there are no indications of landscape, we cannot tell where the events are taking place. Since there are no painted labels, we can’t be sure who we are looking at. Despite these ambiguities, there is no question that this scene is telling a story.

This vase was made during the Greek Geometric period. It is an unusual type of krater, or large mixing bowl, with a spout that is visible just above the middle of the ship. A talented artisan working in Athens crafted the vessel around 735 B.C.E., when ceramic production was thriving in the city. Throughout the Geometric period, craftspeople used an artistic style known as the Geometric style to decorate their products. The style gets its name from its use of basic, geometric shapes, and gives its name to the period in which it was most popular. In the following paragraphs, we will first discover how the artist who made this vessel used the Geometric style to decorate it. We will then consider what story is being told here and contemplate what its meaning was in its original context.

Geometric style

Many characteristics of the Geometric style are visible on this krater. To identify some of them, let’s first look more closely at the couple who are preparing to board the ship.

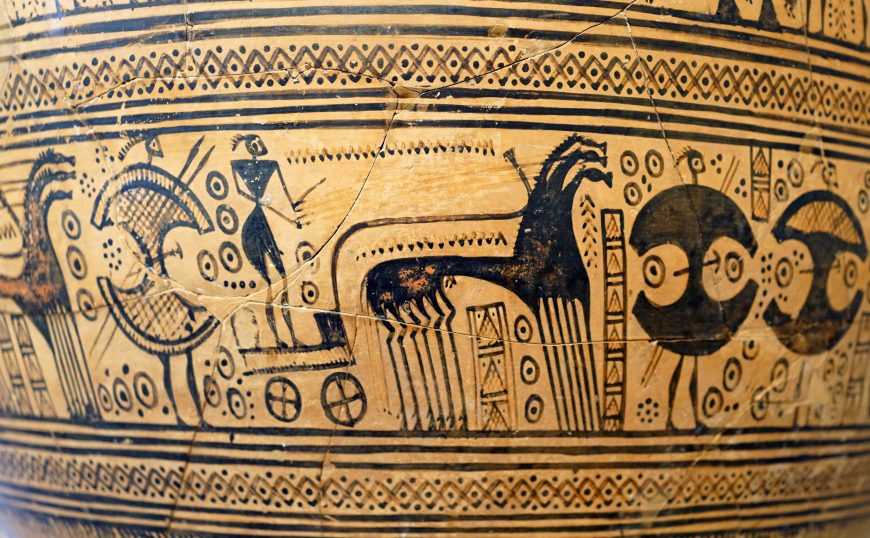

Couple (detail), krater with ship scene, c. 735 B.C.E., ceramic (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

The woman on the left is rendered with a series of simple shapes. Her torso is a triangle, narrowing into an impossibly slim waist. Her arms are rectangles, as are her spread fingers. Her skirt is a slightly curving rectangle that is further decorated with a cross-hatched pattern, suggesting she is wearing a patterned garment. Even her face is made up of basic shapes, including a circle for her head with two protrusions on the right indicating her nose and chin. Her hair is added with a series of curving lines. The man at the right also has a round head with two protrusions representing his nose and chin, but he does not have long hair. His torso is triangular and his narrow waist attaches to his moving legs. Since he is not wearing a skirt, we can see the shape of his legs more clearly. Muscles are suggested by curving lines at the thighs and calves.

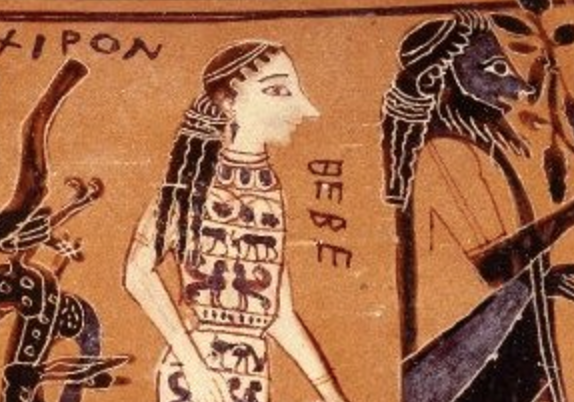

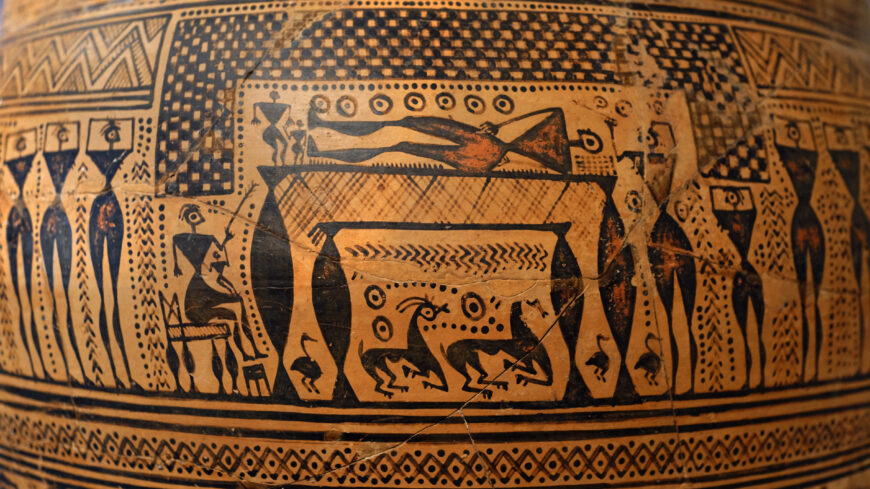

Funerary scene (detail), krater, attributed to the Hirschfeld workshop, c. 750–735 B.C.E., ceramic (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Such pared down renderings of human forms are typical of the Geometric style. We see similar representations of people on large funerary vessels made around the same time in Athens. Consider, for example, the burial scene painted on an enormous vase that was once used to mark a grave. Here the deceased lays horizontally on a bed while other figures mourn him, their hands atop their heads as they tear their hair in grief. The people in the funerary scene also have triangular torsos, tiny waists, and rectangular but muscular legs. They are simply rendered, but their actions are clearly conveyed by their postures, just as we see in the ship scene on the krater.

More typical Geometric stylistic elements present on both of these vessels are the numerous filling ornaments that surround the figures. Stacks of zig-zags fill the space between the couple approaching the ship and float around the boat itself. These decorations do not add to the story, but enrich the visual experience of the vase, adding even more ornament to an already densely decorated surface. Additional dots, lines, and zig-zags appear around the narrative panel, filling almost the entirety of the vessel with decoration.

The method the artisan used to paint this vessel was also particularly popular in the Geometric period. The figures are almost entirely filled in with paint. No details are incised, and no colors are used other than the primary brownish pigment. The only elements that are not fully filled in are the empty spaces in the woman’s checked skirt. This method of painting vases with filled-in patches of color is known as the silhouette technique. It was abandoned just after the end of the Geometric period, when a new technique that allowed more detail was developed.

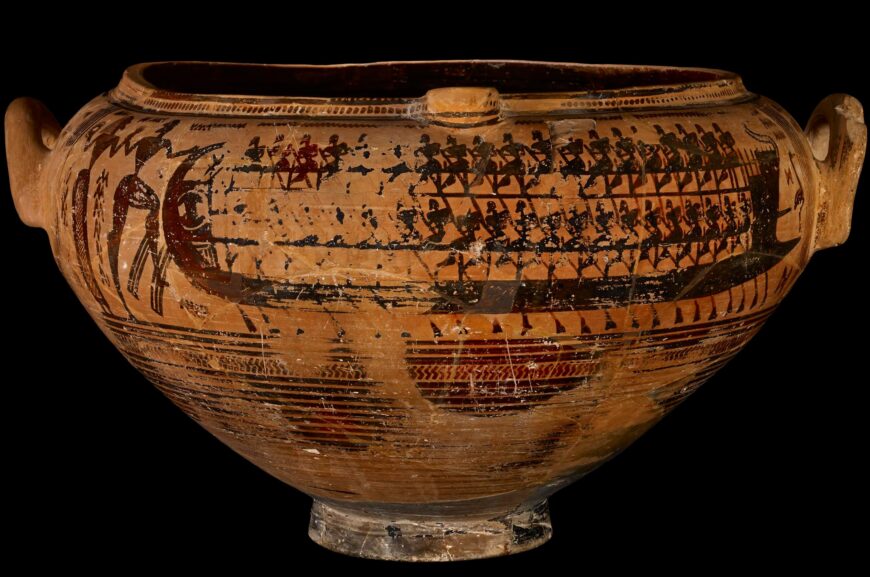

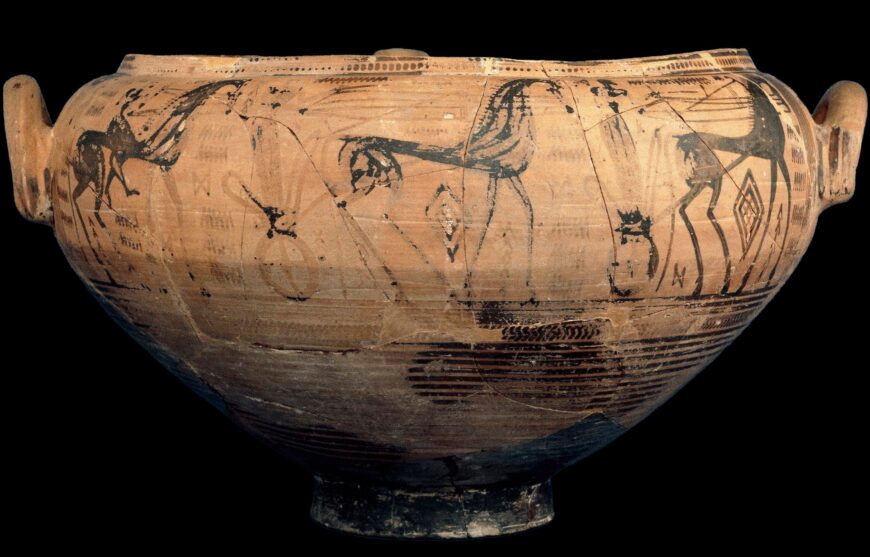

Reverse of krater with ship scene, c. 735 B.C.E., ceramic, 30.5 x 38 cm (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

All of these Geometric stylistic elements are also visible on the back side of the krater, which is not as well preserved as the front side. Here we see a chariot procession moving from left to right. The horses’ legs, necks, and torsos are skinny rectangles. The men who ride in the chariots have triangular torsos. Filling ornaments, including zig-zags, triangles, and diamonds, occupy the empty spaces between the figures. The silhouette technique is used throughout, though it is now faded in places.

Form, function, and narrative

The style of decoration on our krater is typically Geometric in many ways. However, its narrative scene with a couple approaching a ship is unusual and has few parallels in Greek Geometric art.

The precise interpretation of this scene has been the subject of scholarly debate for decades. Some have suggested that the vase must depict a specific myth, with a specific hero leading a specific woman towards the boat. For instance, John Coldstream is one of several scholars that has suggested this is the hero Theseus leaving the island of Crete with his bride Ariadne. [2] In some versions of the myth about Theseus visiting Crete, Ariadne helps Theseus triumph over a difficult challenge by holding a crown of light—Coldstream and others believe the wreath-like object in the woman’s hand is Ariadne’s crown. But other scholars point out that the crown of light is only referenced in versions of Theseus’s myth that were written down long after the Geometric period ended. [3] Furthermore, wreaths that have nothing to do with Ariadne or Theseus are found in other Geometric Greek images, sometimes held by dancers. [4] These kinds of specific mythical interpretations are tempting, but the absence of precise details and labels in the image makes it impossible to definitively agree on one. An exact interpretation of its iconography thus remains elusive.

In recent years, the art historian Susan Langdon has proposed a new interpretation of this krater that takes into account its decoration, shape, and findspot. [5] Langdon points out that the relationship between the couple is clear: the man is grasping the woman’s wrist as he steps onto the boat, a gesture associated with dominance. This posture likely suggests that the woman is being taken by the man as a bride in a kind of marital abduction. While the image may look violent to us today, it could have symbolized a relatively peaceful union of a man and a woman for ancient viewers. Langdon notes that while the vessel was made in Athens, it is said to have been found in Thebes, a neighboring city. She suggests that the vase was made to celebrate the marriage of two elites, one from each city, and that it was used during the marriage rituals. The ship scene could commemorate their union, while the chariot procession on the back might reflect the high status of the families involved, as only wealthy people owned horses during the Geometric period. [6] This ingenious reading of the vessel explains how the form, function, and narrative scene of the vessel might have worked together to satisfy the needs of its original owners.

Still, the exact meaning of the ship scene is ambiguous. Perhaps it was made to celebrate a real, elite marriage, as Susan Langdon proposes; perhaps it was meant to depict a particular myth starring famous ancient Greek heroes. Although we can’t identify the narrative on the vessel with total confidence, we can still recognize the innovations of its creator. The craftsperson who made this vessel was the first Greek Geometric vase painter to depict a woman with long hair and a patterned skirt, and the first to show a boat with two rows of oarsmen. His innovations continue on the reverse of the vessel, where he painted the first charioteer wearing a long robe and the first man riding atop a horse. [7] He crafted a large, functional vessel of unusual form and decorated it with a unique scene, using the Geometric representational style to create a legible image. Even as we wonder about who exactly is represented on this vase, we can appreciate it as an accomplished work of Geometric art that reveals its creator’s desire to tell a story with images instead of words.