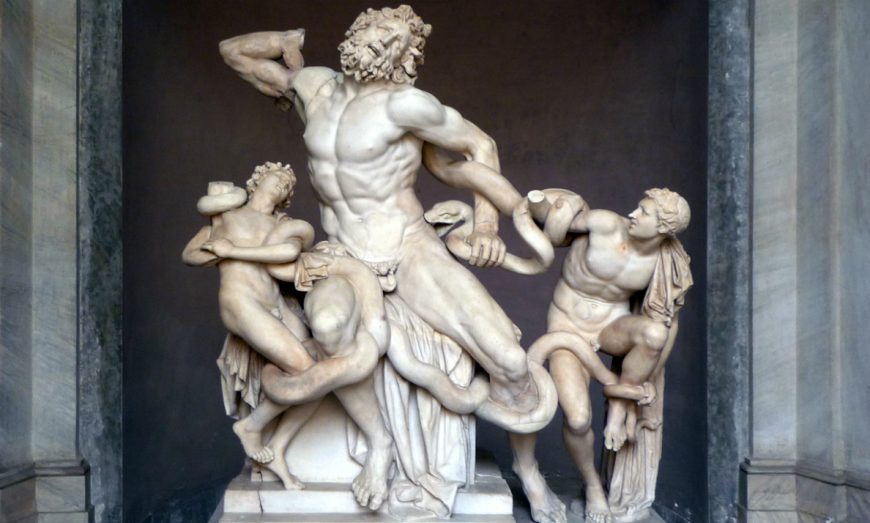

This early Greek depiction of the idealized male form displays power and poise in his nudity and steadfast gaze.

Marble Statue of a kouros (New York Kouros), c. 600–580 B.C.E., Attic, archaic period, Naxian marble, 194.6 x 51.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the room in the Metropolitan Museum of Art that’s devoted to Archaic Greek sculpture.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:11] Most of it funerary, so sculpture meant to mark graves.

Dr. Zucker: [0:15] I just saw a man walk over to this 2,600-year-old sculpture and put his hand as a kind of caress against her backside. Of course, this is wrong in so many ways. What happened is for him, 2,600 years collapsed. That sculpture was this sensuous female figure.

Dr. Harris: [0:32] That man walking through the Met felt something that the ancient Greeks felt when they made these sculptures. They were a lot of other things, but they were also deeply sensual.

Dr. Zucker: [0:42] We came into this room to look at a kouros, a funerary sculpture of a young man. It’s a life-size marble.

Dr. Harris: [0:49] We should say a nude young man because as we’ve just learned, although the female figure is clothed, when the Greeks made these, the female figures were clothed and the male figures were nude. Both were equally sensual.

Dr. Zucker: [1:00] The only thing he’s wearing is a little choker around his neck, and a headband, a fillet. What struck me was that the man who sculpted this kouros figure was creating something that was meant to trespass lifetimes, to exist longer than any individual.

Dr. Harris: [1:17] It’s made of stone, and it endured for millennia. It was made to mark a tomb. Indeed, it was meant to last and to serve as a reminder not only of his life but of his connection to his family, of his family’s lineage across time.

Dr. Zucker: [1:33] It’s important to note that this would have been made for an aristocratic family. It’s also important to note that this is not a portrait in the way that we think of that in the modern era. It’s not in any way a likeness. It is, instead, a symbol.

Dr. Harris: [1:45] An ideal of manhood, of perfection. I’m interested in the way that in the 6th century [B.C.E.], we have sculpture during this Archaic period that’s made largely for aristocratic families, for the elite in Athens and the surrounding area.

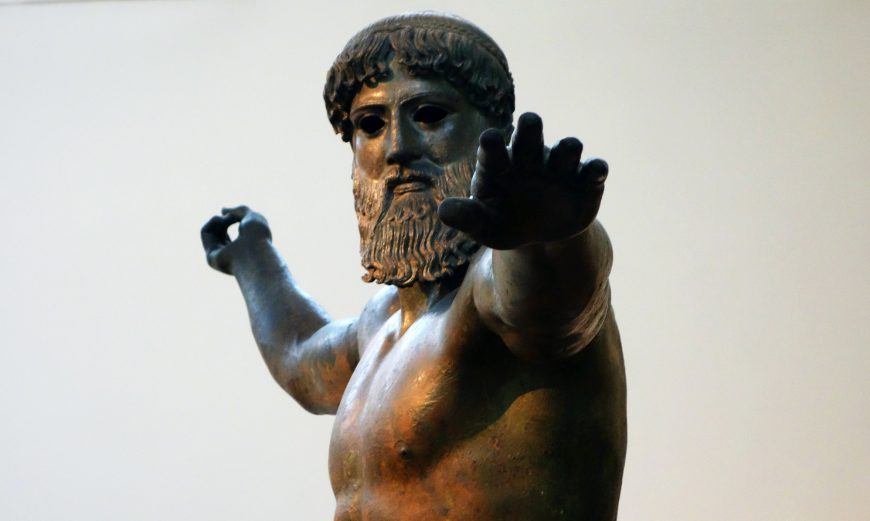

[2:02] When we move into the 5th century [B.C.E.], with the developments toward democracy, we have sculptures that are made and commissioned for the state and by the state that are very different than what we see during the Archaic period.

[2:14] This early Greek image, so clearly dependent on the ancient Egyptians. We could go through the ancient Egyptian galleries and see figures very much like this. Usually they’re wearing a loincloth or some kind of clothing representing the pharaoh, representing the kings of Egypt.

Dr. Zucker: [2:29] There’s a real distinction here, which is that this figure is cut away from the stone. The stone between his legs is removed. There is no stone backing. He stands upright in this gallery, in the middle of the room, completely unaided by anything but his own two legs. There is a kind of extraordinary autonomy that results.

Dr. Harris: [2:48] Well, autonomy and so much more, because when the Egyptians embedded that figure in the stone, they gave it a sense of transcendence, of timelessness, of being godlike in some way.

[2:59] By freeing the figure from the stone, we immediately have a sense of him being much more like us. Much more human.

Dr. Zucker: [3:06] Existing in our space.

Dr. Harris: [3:07] Exactly. Moving into our space, striding forward.

Dr. Zucker: [3:11] Look at his stance. His shoulders are squared. His hips are squared. His leg is forward.

Dr. Harris: [3:17] There’s a sense of movement, but no real movement.

Dr. Zucker: [3:20] Those limbs are locked in place, even as they’re representing symbolically the forward movement of the figure.

Dr. Harris: [3:27] So during the Classical period, in the next century, the Greeks will make figures that stand in contrapposto. That is, they’ve shifted their weight. Their weight is firmly on one leg. One knee is bent and the whole body becomes asymmetrical.

[3:39] Here, really, aside from that one foot being forward, the figure is very symmetrical. It occupies a very strange place between being here present with us and also being absent from us. That’s in the gaze, too. There’s a way that he looks past us. He doesn’t engage us.

Dr. Zucker: [3:57] The lack of contrapposto, the symmetry, does place him in some ways firmly in a world that is not ours. A kind of ideal, perfect world.

Dr. Harris: [4:06] His features have been reduced to geometric shapes. Even his body parts are very geometric.

Dr. Zucker: [4:13] As a result, very much isolated from each other. You have an arm which seems distinct from the torso, as opposed to creating a smooth transition. In fact, you might even look at this sculpture and see it as very cubic.

[4:24] Perhaps even referencing the four sides of the stone that this was carved from. One can imagine a block of marble that the sculptor is approaching from four different sides.

Dr. Harris: [4:33] Actually drawing the figure on those four sides and then cutting the stone away and using a system of proportions. Very much like the Egyptians did.

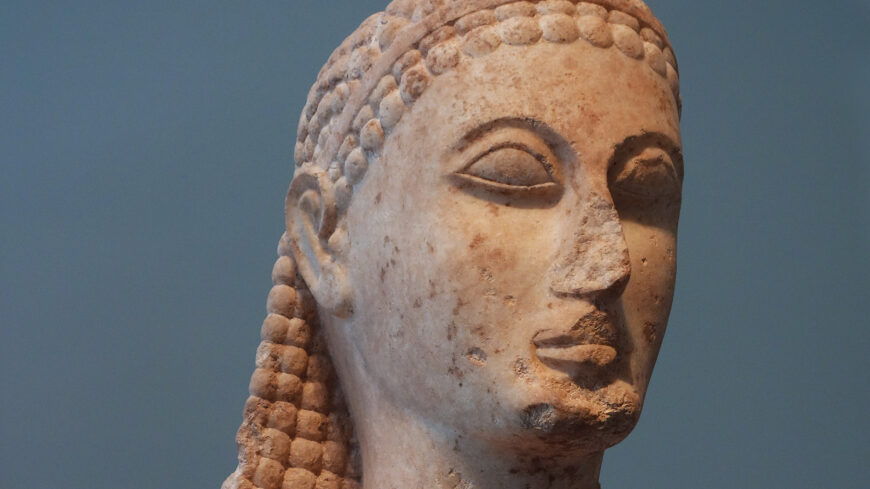

Dr. Zucker: [4:43] The sculptor has been really careful about creating a kind of alternation between flat areas, for instance of the face, against much more complex and deeply carved areas, the braided or beaded hair, which creates this beautiful frame for the face.

[4:57] Now this is a huge block of stone. It weighs about 2,000 pounds. It’s about a ton of stone that remains. It really is a tremendous feat, being able to create a sculpture that is balanced and supported on essentially two narrow ankles.

Dr. Harris: [5:11] Without falling over.

Dr. Zucker: [5:12] But you’ll notice that the sculptor has left a little bit of a bridge between the clenched fists at his side and his hips to help support those arms. Because if they were free-hanging, they would be too fragile.

Dr. Harris: [5:24] Even so, you can see that this sculpture is 2,600 years old. It was obviously put back together by the museum. Over time, it broke. It’s always interesting to look for that and to notice what may be a reconstruction and what’s original, although here, I think everything that we’re seeing is original.

[5:41] [music]

New York Kouros, c. 600–580 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In 1932, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City purchased an over life-size statue of a nude male youth. The ancient Greek sculpture was said to have been found near the town of Phoinikia in Attica, a region of Greece that is home to the city of Athens. It is an example of the kouros (plural: kouroi) type of Greek sculpture. Kouroi are statues of young, nude men that were popular in the Archaic period. Unlike many kouroi, the kouros in New York is not entirely nude: he wears a choker style necklace and a fillet in his hair. Today, the statue is known as the New York Kouros because of its current location. Scholars date its creation to c. 600–580 B.C.E., making it one of the earliest examples of the kouros type.

Map of the Aegean with the probable findspot and material source of the New York Kouros, c. 600–580 B.C.E. (underlying map © Google)

New York Kouros, c. 600–580 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

From Naxos to Attica

Some 2600 years ago, the New York Kouros functioned as a grave marker in Attica. Although it stood above a grave in this mainland Greek region, it is made of a type of marble that comes from hundreds of miles away, on the island of Naxos in the Cyclades. [1] Naxos has large quantities of high-quality marble, notable especially for its shininess. People living on the island were already using the local marble to craft life-size statues of humans in the Protoarchaic period. By c. 600 B.C.E., they were exporting many of their sculptures to areas throughout the Greek world, including Attica. [2] Although it remains somewhat unclear whether Naxian sculptors traveled to fulfill commissions, it is plausible that the skilled Naxian sculptors did travel to mainland Greece to create large kouroi for local elites beginning in the early Archaic period. [3]

Rigidity and symmetry as Archaic ideals

The early Archaic date of the New York Kouros is confirmed by its style. Overall, the New York Kouros is rigid and stiff, and seems to recall the four-sided marble block it was carved from. Greek sculptors who created kouroi may have been inspired by Egyptian stone sculptures they heard about or saw in the Protoarchaic and early Archaic periods. Indeed, some scholars believe the New York Kouros is so similar to Egyptian sculptures that its creators must have used the same rigid system of proportions that Egyptian sculptors did. [4] However, Jane Carter and Laura Steinberg’s recent reevaluation of statistical comparisons between this kouros and the Egyptian canon of proportions disproves this. [5] Although this kouros is block-like and carefully proportioned, it conforms to a distinctly Archaic Greek ideal. It has an impossibly large head, which sits atop a long neck that is adorned with a knotted ribbon. [6] It has broad shoulders, a long waist, and short thighs. [7] To prevent the marble of the kouros from breaking, the sculptor thickened its ankles slightly and left its fists attached to its thighs with narrow strips of stone. [8]

The sculptor’s goal was not to create a highly realistic image that closely resembled the deceased whose grave the kouros marked, but instead to create one that embodied the ideal of the period. For that reason, the anatomy of the figure is rendered in a series of patterns that appear almost decorative. The figure’s pelvis is distinguished by a prominent raised line that resembles a V, while the upper portion of his abdomen is marked out by a less prominently raised line that looks like an upside-down V. [9]

Head (detail), New York Kouros, c. 600–580 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The sculptor’s focus on symmetry and pattern is especially noticeable in the face and hair of the figure. The cheeks are flat, while the eyebrows are indicated by single curving lines. The ears are curled like volutes. The hair is rigidly patterned, made up of a series of squared off strands that fall heavily on the figure’s back. Although none of these characteristics could have closely resembled an actual human, they are easily recognizable as human body parts. They have been made decorative to create a more perfect image of an elite male. In the Archaic period, the entire statue would have appeared even more ornamental because it would have been painted. Traces of pigment are still visible in the reddish tones that appear on the kouros’s fillet and hair.

Left: Head (detail), New York Kouros, c. 600–580 B.C.E., marble (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; right: head of a kouros (the so-called Dipylon Head), c. 600 B.C.E., marble, 17 inches high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Kouros (the so-called Sacred Gate Kouros), c. 600–590 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 10 inches high (Kerameikos Museum, Athens; photo: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Relationship with other kouroi

The highly decorative style of the New York Kouros is typical of the earliest Athenian kouroi. The head of another kouros that was found in Athens so closely resembles the New York Kouros that some scholars believe the two were created in the same workshop. [10] The kouros’s head, now known as the Dipylon Head because it was found near the Dipylon cemetery in Athens, closely resembles that of the New York Kouros. Both kouroi have large, staring eyes under curved eyebrows, volute-like ears, and fillets in their hair. They have similar hairstyles, with heavy locks made up of squarish individual elements, though the Dipylon Head’s strands of hair interlock with one another rather than lying next to each other in the more grid-like pattern we see on the New York Kouros. [11]

In 2002, archaeologists working in Athens found yet another kouros that closely resembles both the Dipylon Head and the New York Kouros, further enhancing our understanding of what kouroi looked like in the early 7th century B.C.E. This recently discovered kouros is known as the Sacred Gate Kouros because of its findspot. The Sacred Gate Kouros is more muscular than the New York Kouros, but it is similarly proportioned, and especially similar in the appearance of its hair and face.

Left: New York Kouros, c. 600–580 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); right: Anavysos Kouros, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

As the Archaic period progressed, the ideal form of the kouros shifted. These changes are especially noticeable when we compare the New York Kouros to the Anavysos Kouros, which was made about 60 years later. Both kouroi served as grave markers, perhaps even in the same cemetery, but they embody different ideals. [12] The Anavysos Kouros is more naturalistic, or lifelike, than the earlier New York Kouros. Its muscles are carved more deeply and appear more rounded, and thus more closely resemble the proportions of an actual young man. The Anavysos Kouros’s proportions are also more realistic, with a smaller head, thicker waist, and less elongated calves. Both statues are nude and muscular, and both have elaborate hairstyles. Both also take slight steps forward with their left legs, advancing despite their stiffness and rigidity. However, it is clear that as the Archaic period continued, wealthy customers and the sculptors who worked for them were interested in more rounded and naturalistic kouroi.

New York Kouros, c. 600–580 B.C.E., marble, 6 feet 4 inches high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A perfected memorial

The New York Kouros now stands in the center of a gallery in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. But why would a wealthy Athenian living in 600 B.C.E. want to mark a loved one’s grave with this statue? It could not have closely resembled the deceased, or any other real person. Instead, it projected a perfected image of the deceased to all who passed it. Kouroi were expensive monuments, and would have been available to only the most elite customers. The presence of the kouros would indicate to ancient viewers that the person who was buried beneath it was wealthy and honorable. The kouros’s nudity allows it to display its perfected, muscled body. Youth and strength were highly valued by the ancient Greeks, who understood these characteristics to be crucial to achieving success in athletic and military competitions. [13] The decorative symmetry of the kouros was in keeping with the preferred style of the early Archaic period. Gazing out over the heads of those who walked by it, the New York Kouros would draw attention to itself and the person whose grave it marked, preserving the memory of the deceased and associating him with ideals of youth and strength.