Nikandre statue, c. 650 B.C.E., marble, 1.75 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0)

Finding Nikandre

In the late 1800s, while excavating an important ancient Greek sanctuary on the island of Delos, archaeologists discovered a life-size statue of a woman. Although the statue was broken in a few places and heavily worn, it was immediately recognized as impressive because of its size and its material. [1]

The sculpture is made of high-quality marble, a shiny, whitish stone. Today, archaeologists believe it was one of the first life-size stone statues produced in ancient Greece. Its style suggests that it was made sometime around 650 B.C.E., during the Protoarchaic period. An inscription that runs down the statue’s skirt gives us tantalizing clues about where it was made and who it was made for. This inscription also gives the statue its modern name—it tells us that the image was dedicated by a woman named Nikandre as a gift to a god, and so we today call this statue Nikandre. In the following paragraphs, we will look more closely at this statue, considering what type of statue it is, what its style tells us about when it was made, and how it was related to the real Nikandre who dedicated it.

Side view, Nikandre statue, c. 650 B.C.E., marble, 1.75 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

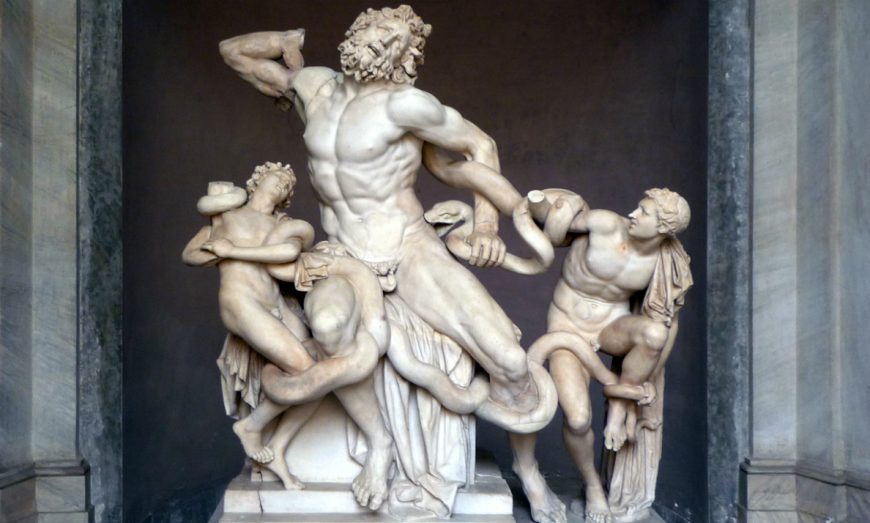

The first of the korai

The Nikandre statue represents a female figure. She stands stiffly upright, her arms held closely to her side, her legs straight and unmoving. She is shown wearing a long dress that reaches down to her feet and a cape over her shoulders. [2] There is little suggestion of her body beneath the dress, though her narrow waist is highlighted by a small belt. Although her clothing now seems rather plain, it would have been brightly painted when it was first made and set up as a votive offering in the sanctuary on Delos, making it far more visually elaborate. [3]

This type of Greek statue that shows a richly dressed woman in a frontal, stiff posture is known as a kore (plural: korai). During the Archaic period, korai and their male counterparts, kouroi, became extremely popular. Wealthy ancient Greeks often gave them to the gods as gifts, setting them up in sanctuaries where they could be viewed by both the gods and other worshippers. These highly idealized representations of human figures displayed the physical perfection that aristocrats valued and equated with moral excellence. The Nikandre kore was made before the Archaic period began in 600 B.C.E. In fact, she may well be the first marble kore ever made. [4] Like the korai made after her, this kore uses expensive marble to display the ideal of the period in which it was made. However, the Nikandre kore differs from later Archaic korai in some ways because she was made to conform to the Protoarchaic ideal of femininity.

Left: Nikandre statue, c. 650 B.C.E., marble, 1.75 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0); right: Peplos Kore, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 1.2 m. high (Acropolis Museum, Athens)

Daedalic style

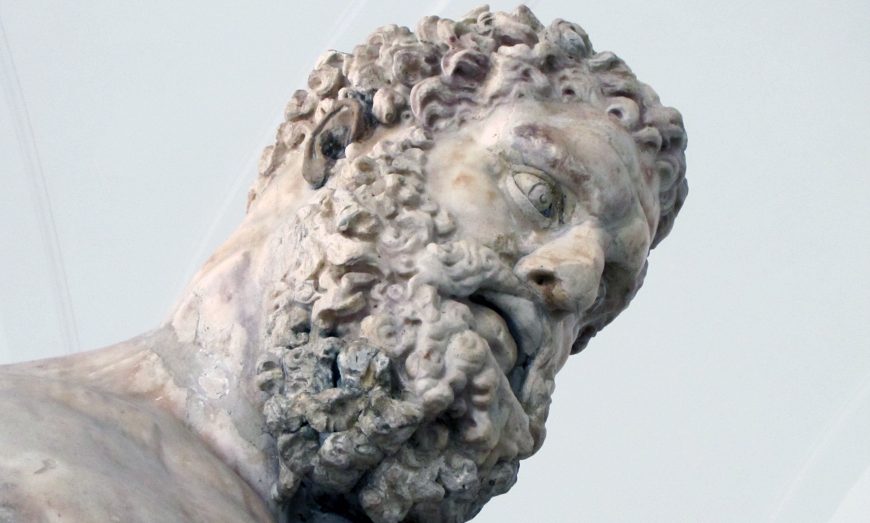

When we compare the Nikandre kore to an Archaic kore like the Peplos kore, we can identify the differences between the Protoarchaic and Archaic styles of representation. The Nikandre kore has a face shaped like a triangle with a large, rounded chin. Her hair is heavy, almost like a wig, and falls over her shoulders in two triangular-shaped masses. The top of her head is flat. All of these elements of the Nikandre kore’s head distance her from the more naturalistic, Archaic Peplos kore.

The Nikandre kore is entirely symmetrical, whereas the Peplos kore shifts slightly on her feet and once held her left hand out before her. There is almost no suggestion of the female body beneath the Nikandre kore’s heavy dress, but there is a hint of a woman’s body under the Peplos kore’s gown, particularly at her chest. The Nikandre kore is overall much flatter than the Peplos kore, more plank-like in shape, using simple geometric shapes to convey the feminine ideal of its time.

Left: Nikandre statue, c. 650 B.C.E., marble, 1.75 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0); right: Lady Sennuwy, c. 1971–1926 B.C.E., granodiorite, 1.7 m high (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Art historians call this style of representation—which shows flattened, symmetrical figures in frontal, stiff poses, with triangular faces and heavy, wig-like hair—the Daedalic style. The Daedalic style was popular during the Protoarchaic period. It gets its name from a mythical sculptor named Daedalos, whom ancient Greeks believed lived on the island of Crete. [5] The ancient Greek sculptors who developed the Daedalic style seem to have borrowed some of its stylistic elements from their neighbors in Egypt. [6] Egyptian craftspeople had been making rigid, symmetrical stone sculptures of idealized human figures for centuries before Greek craftspeople began to experiment with similar representations in the Protoarchaic period.

If we compare the Nikandre kore to an Egyptian statue of a seated woman, we can see the many similarities between them: both are rigid and frontal, wearing long dresses, with heavy, wig-like hair, and both are made of stone. During the Protoarchaic period, Greeks and Egyptians began interacting more frequently as trade throughout the Mediterranean thrived. This period of heightened cross-cultural interaction may have enabled Greeks to see or hear about Egyptian sculptural styles that they then borrowed for their Daedalic sculptures.

Left: Nikandre statue, c. 650 B.C.E., marble, 1.75 m high (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Gary Todd, CC0 1.0); right: Lady of Auxerre, c. 640–620 B.C.E., limestone, 0.75 m high (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

The characteristics of this Greek Daedalic style are also visible in another, smaller statue of a woman that is today known as the Lady of Auxerre. Both have triangular faces and heavy, wig-like hair. They are frontal and highly symmetrical, though the Lady of Auxerre is shown in a slightly more active posture, raising her right hand to her chest. Both wear long garments with capes over their shoulders. Both rely on basic, geometric forms to create simplified yet idealized representations of women. The two statues are different in many ways: unlike the Nikandre kore, the Lady of Auxerre is well under life-size, made of limestone, and probably originally functioned as a grave marker on the island of Crete. However, both use the same formal elements to project an ideal that was valued by ancient Greek viewers throughout the Protoarchaic Mediterranean.

Inscription and identity

The Nikandre kore uses the Daedalic style to represent a female figure. But who exactly does she represent? Since korai are so highly idealized, it is often impossible to tell who exactly they represent unless they are accompanied by an inscription or carry some identifying objects. A kore might represent the goddess to whom she was dedicated, a mortal woman who dedicated her or was related to her dedicator, or some generic idealized female. The Nikandre kore has a long inscription on her left leg that provides more information about her dedicator’s identity and the circumstances that led to her creation and dedication, but it does not tell us who the statue represents. The inscription reads:

Nikandre dedicated me to the far-shooter arrow-pourer, the daughter of Deinodikos of Naxos, preeminent beyond other [women], sister of Deinomenes, and [now] wife of Phraxos Translated by Joseph W. Day [7]

The inscription is written in the first person, as if the statue might say the words written on its skirt. The text tells us that Nikandre—a woman—dedicated the statue to a divinity described as “the far-shooter arrow-pourer,” a reference to the god’s excellence in archery. The statue was found in the sanctuary on Delos, which is sacred to the god Apollo, whom the ancient Greeks believed to be an excellent archer. However, most scholars believe Nikandre actually dedicated this statue to the goddess Artemis, who is Apollo’s twin sister and was also known for her talent with a bow, in part because the statue was found near a temple dedicated to Artemis. [8]

We learn more about Nikandre in the rest of the inscription. She is described as “preeminent beyond other [women],” perhaps a reference to her moral excellence and/or beauty. [9] She is also identified in relation to her male family members. We read that her father is a man from Naxos, suggesting that she too is from that island, which is close to Delos. Both Naxos and Delos are part of the Cyclades, a group of islands in the middle of the Aegean Sea. Naxos is well known for its high-quality marble and the Nikandre kore is made of Naxian marble. [10] Nikandre was clearly proud of her ties to Naxos, reiterating them in the statue’s inscription and in its material.

Head (detail), Nikandre statue, c. 650 B.C.E., marble (National Archaeological Museum, Athens; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

We also discover the name of Nikandre’s brother and the man who is “now” her husband, Phraxos. The inclusion of the word “now” in the inscription gives us a hint about why the statue was dedicated: it is possible that Nikandre dedicated the kore to Artemis when she married Phraxos, to celebrate this important event. [11]

Given her ability to dedicate a life-size marble statue to the goddess Artemis in one of the most important sanctuaries in the ancient Greek world, we can deduce that Nikandre was a wealthy woman from a prominent family. She may have even been a priestess to Artemis who served at Delos until she married Phraxos. [12] Unfortunately, the lengthy inscription does not completely clarify whom her kore is meant to represent. There are holes in the kore’s fists that once held metal objects that would have helped us identify her. If she held a bow and arrow, the kore would be recognizable as Artemis, the goddess to whom the statue was dedicated. It is also possible that she represents an idealized version of Nikandre. Although we’re not sure who exactly she represented, we know that this perfected image stood as a worthy dedication to Artemis and remained linked to its dedicator, Nikandre, through its inscription.

A perfected image

Although the Nikandre kore is so perfected that she is anonymous today, she still reveals much about Protoarchaic Greek art. She is perhaps the earliest kore ever made in stone and stands at the beginning of a long line of idealized sculptures of young girls that populated sanctuaries throughout Greece in the Protoarchaic and Archaic periods. The sculptor who created her used the Daedalic style to ensure that she would conform to the rigid, symmetrical visual ideals of the Protoarchaic period. The inscription on her skirt tells us that a woman dedicated her, revealing that some women had the ability to leave large, eye-catching votives in major Greek sanctuaries in the mid-7th century B.C.E. Overall, the Nikandre statue shows us the artistic and religious priorities of the people who made her millennia ago.