In 336 B.C.E. a young man named Alexander inherited control of a kingdom called Macedon in the area of modern day Greece. Alexander had military experience but was only 20 years old when his father was assassinated, leaving him in control of a large swath of land at a young age. [1] Over the next 13 years, Alexander aggressively expanded his territory. By the time he died in 323 B.C.E., his territory stretched all the way to modern day India. [2] His Macedonian Empire was one of the largest empires that ever existed. [3] It is one of the reasons that Alexander is today known as Alexander the Great.

Map of Alexander the Great’s conquests, c. 338–328 B.C.E. (map: Generic Mapping Tools, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Alexander the Great ruled his empire long before modern media existed. He could not give televised speeches, nor could he circulate his image and ideas in newspapers. Very few people who lived under his rule ever saw him in person. Instead, Alexander was known to many through his portraits. Ancient authors suggest that Alexander the Great was well aware of the importance of his portraits and controlled them carefully. He had a favorite sculptor, Lysippos, whom he gave special permission to design his sculpted portraits. [4] While no original portrait of Alexander made by Lysippos survives, many copies of his work exist, as do other versions of Alexander’s portraits. Examining these copies can help us understand what is innovative about Alexander the Great’s portraits and how they were crafted to convey a certain message about the ruler to viewers.

Before we look at some of these portraits, we must consider two issues that complicate our study of them. The first is the difference between a portrait and a likeness. Although a portrait is a representation of an individual, it is not necessarily a likeness of that individual, meaning that it does not have to depict the individual as they actually appear. Portraits can remove flaws and exaggerate good features, resulting in idealized images. Of course, we have no photographs of Alexander the Great, so it is difficult to determine what he really looked like, but written sources suggest that he was idealized in his portraits. [5] Alexander the Great and the artists who worked for him were less interested in conveying his exact likeness and more interested in creating portraits that presented him as a capable young ruler.

The second major issue that complicates our understanding of portraits of Alexander the Great is the lack of surviving originals. Most portraits that have been identified as depicting Alexander were probably made long after his death. [6] Some might be copies of famous portraits by important artists like Lysippos, but this is difficult to determine because we can’t compare them to surviving originals. Scholars often rely on literary descriptions of Alexander and his images to identify his portraits. These portraits share some distinctive characteristics that are also mentioned in the written sources. By looking closely at a few of these sculptures we can become more familiar with the defining characteristics of Alexander the Great’s portraits.

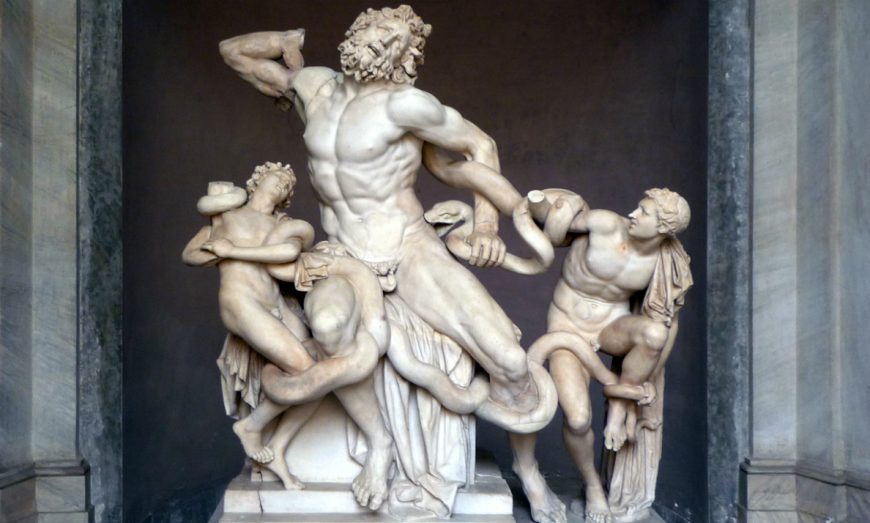

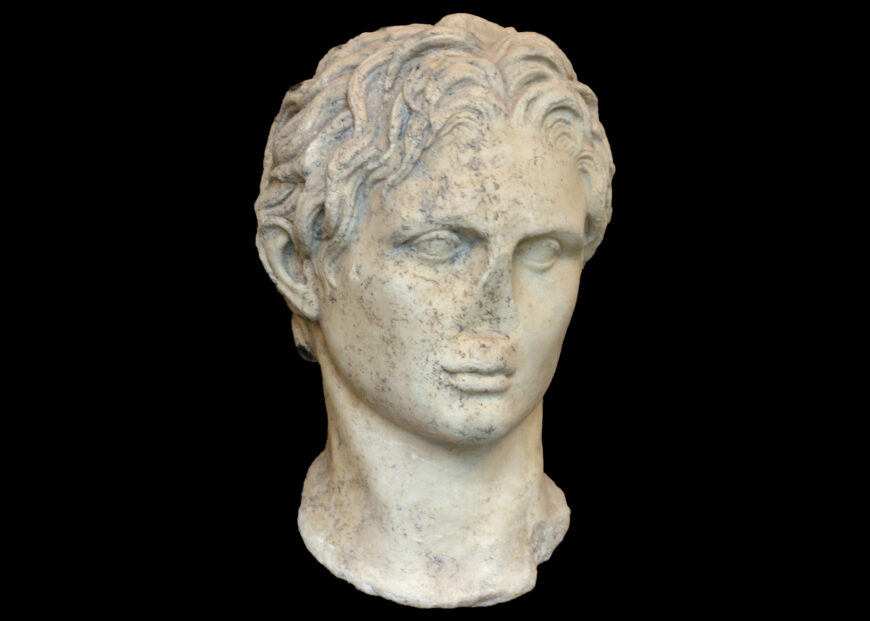

Portrait of Alexander the Great (the so-called Azara Alexander), Roman marble copy of a Greek original, c. 1–50 C.E., 68 x 32 x 27 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

The heads of Alexander

One portrait of Alexander the Great is today known as the Azara Alexander because it was once owned by a man whose last name was Azara. The bottom of this portrait bust is inscribed with Alexander the Great’s name, allowing us to securely identify him. However, we know that this is not a Greek original because the Greeks didn’t make portrait busts. Romans invented portrait busts, which only show the heads (and sometimes shoulders) of an individual. [7] The Roman artist who made the Azara Alexander attached the portrait head to a block-like bust that carries the identifying inscription. Some scholars believe this is a Roman copy of an original Greek portrait of Alexander by Lysippos. [8]

Many of the distinctive characteristics of Alexander the Great’s portraits are visible here. First, Alexander is shown without a beard. Prior to Alexander’s rule, Greek men were typically shown with beards, which signaled their maturity and adulthood. By appearing without a beard, Alexander the Great broke with tradition and emphasized his youthfulness. [9] Many kings that succeeded Alexander imitated his beardlessness in their own portraits.

Another defining trait of Alexander the Great is his hairstyle. The two locks of hair at the center of his forehead stand straight up and are parted slightly off center in a style that is called anastole. His hair is thick, with many long, wavy pieces. Ancient authors describe Alexander the Great as being lion-like in personality, and in his portraits, his leonine nature is expressed through his hairstyle: in its fullness and wildness, his hair recalls a lion’s mane. [10] Alexander’s hairstyle thus makes him more easily recognizable and conveys his lion-like fierceness.

Additional features typical of Alexander’s portraits are present in the Azara Alexander. The head turns slightly, adding a liveliness to the image, as if Alexander is engaged and responsive. The head also has a far off gaze, which is sometimes described as “melting” and was apparently a real physical trait of Alexander. [11] Ancient authors mention all four of these traits (beardlessness, anastole of leonine hair, turning head, and melting gaze) in their written descriptions of Lysippos’s portraits of Alexander, supporting the idea that this may be a Roman copy of a Greek sculpture by Lysippos. [12]

Portrait of Alexander the Great (the so-called Alexander Schwarzenberg), Roman marble copy of a Greek original, c. 20 B.C.E.–20 C.E., 35.5 cm high (Glyptothek, Munich; photo: public domain)

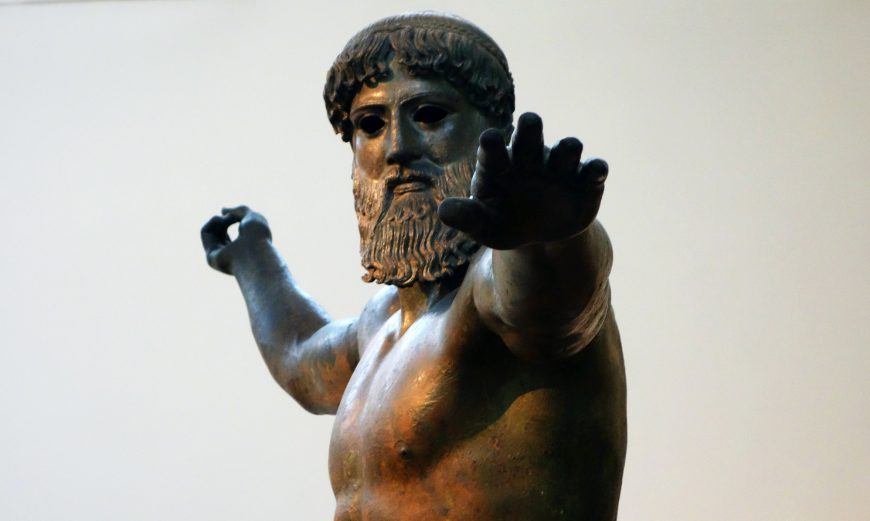

Other surviving portrait heads of Alexander the Great also have these defining traits. One head of Alexander that is now in Munich has also been recognized as a Roman copy of a Greek original by Lysippos. Alexander is beardless, with the typical anastole and leonine hair. His head turns towards the right, engaging the muscles in his neck, and his deep set eyes seem to gaze off into the faraway distance. [13] While we can’t be totally sure that this Roman statue is imitating a Greek sculpture by Lysippos, we can identify it as a portrait of Alexander.

The body of Alexander

We have learned to recognize Alexander the Great based on his distinctive features. But during his lifetime his sculpted portraits depicted his entire body, not just his head. To get a sense of how the rest of Alexander was depicted, we must once again turn to Roman copies of Greek statues.

Alexander the Great (the so-called Nelidow Alexander), Roman copy of a Greek original, 2nd century C.E., bronze, 12.1 x 5.3 x 3.6 cm (Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge)

One such Roman statue is recognizable as Alexander because of its leonine hair with anastole, beardlessness, and faraway gaze. Here we find the king in the nude. He once held a spear in his left hand, planting it into the ground to indicate he is in control of the land upon which he stands. Alexander poses almost casually, showcasing his perfected musculature. His idealized body emulates the ideal that was developed by Greek sculptors during the High Classical period. [14] Alexander was a great fan of Greek culture and believed himself to be descended from the Greek heroes Herakles and Achilles. Indeed, in this portrait, he is so idealized that he looks like a Greek hero. Despite this he is still recognizable as Alexander because of his face and hair. Through the idealization of the nude body, this portrait exaggerates the physical prowess and power of the real ruler it represents.

An unconventional Alexander

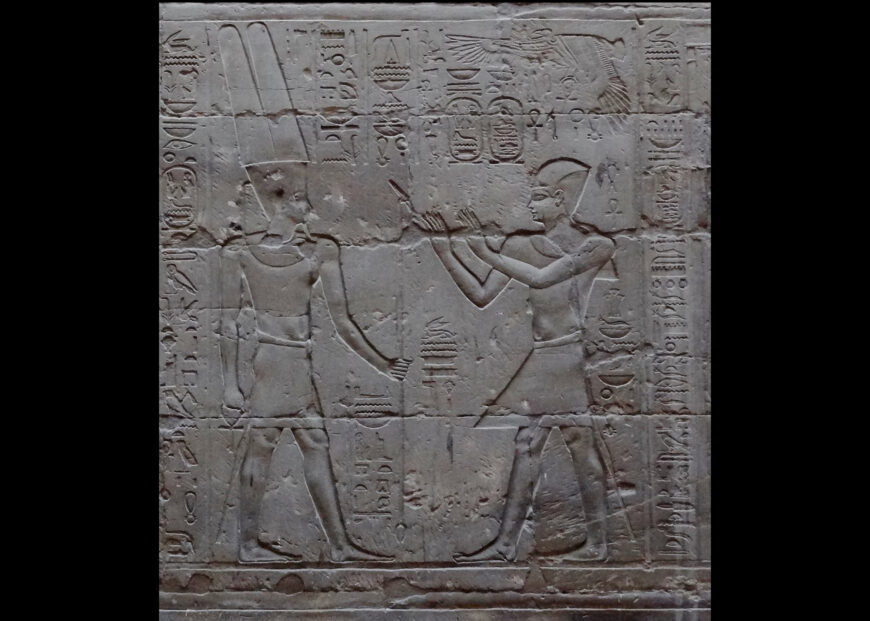

All of Alexander’s portraits were carefully crafted to convey that he was a worthy leader, but a few of them broke with the conventional format defined above to show him in a more local style. These representations are still designed to prove his legitimacy to rule, but because they are doing this for a different audience, they look different than typical portraits of Alexander. For example, sometime after Alexander conquered northern Egypt, he made additions to a centuries-old temple at Karnak to simultaneously demonstrate his respect for the Egyptian gods and his power. The chapel he commissioned was decorated with dozens of reliefs that show him worshiping the Egyptian gods.

Alexander the Great from the Luxor Temple, Karnak, Egypt, c. 325 B.C.E., sandstone, 1.4 m high (photo: Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0)

In this example, we see Alexander on the right approaching a god. He has neither leonine hair nor anastole, and his faraway gaze is gone. Instead, he is represented in a highly conventional Egyptian manner. [15] He wears an Egyptian kilt and headdress, while his body is shown in composite view, with his chest frontal and his head, arms, and legs in profile. His idealized musculature matches that of the god he faces. In fact, Alexander looks so much like other Egyptian rulers in this image that we can only be sure this is him because he is accompanied by hieroglyphs that spell out his name. Alexander has adapted the imagery of local Egyptian rulers in this temple so that he would be more easily recognizable as a leader to the Egyptians who visited this holy structure.

The legacy of Alexander’s portraits

Alexander the Great’s portraits were designed to portray him as an effective ruler. The goal of these portraits was not to represent Alexander exactly as he appeared, but to highlight his best traits and convey his strength to all who saw them. Certain physical characteristics make Alexander identifiable to us even today, including his clean shaven face, his long curling hair and anastole, and his faraway gaze. These same traits would have also enabled ancient viewers throughout his empire to recognize him. Occasionally Alexander’s portraits conform to a different ideal so that they can clearly express his power to a different audience, but even then, their goal is to make him recognizable as a leader.

The Macedonian Empire fractured into several different kingdoms soon after Alexander’s death in 323 B.C.E. Many of the leaders of these Hellenistic kingdoms continued to make portraits of Alexander, honoring him long after his death. These leaders believed that Alexander became a god after he died, so he sometimes acquired new characteristics that suggest his divinity in these later portraits, even while retaining his typical traits.

Coin with head of Alexander the Great, 305–281 B.C.E., silver, 17.25 grams (© The Trustees of the British Museum, London)

For example, in a portrait of Alexander on a coin made in Thrace after his death, Alexander wears a royal diadem. He also has ram’s horns sprouting from his head, which show he is descended from the Egyptian ram-god: the horns show Alexander’s godliness. [16] Despite these new features, Alexander is still recognizable because he is beardless and has his distinctive anastole and curls. The same kings who added such portraits of the deified Alexander to their coins also emulated Alexander in their own portraits, often representing themselves without beards. Alexander the Great’s influential portraits thus lived long after he did, on Hellenistic coins, in Roman copies, and in many other ways.