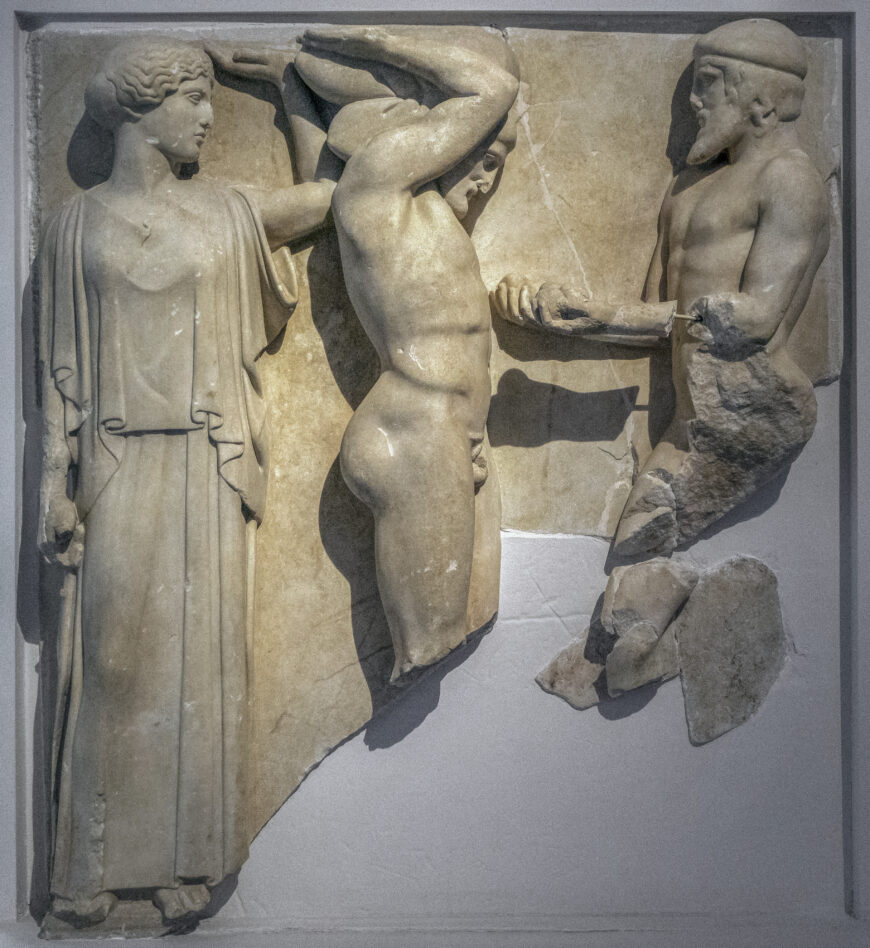

East metope 4 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble, 1.6 x 1.6 m (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

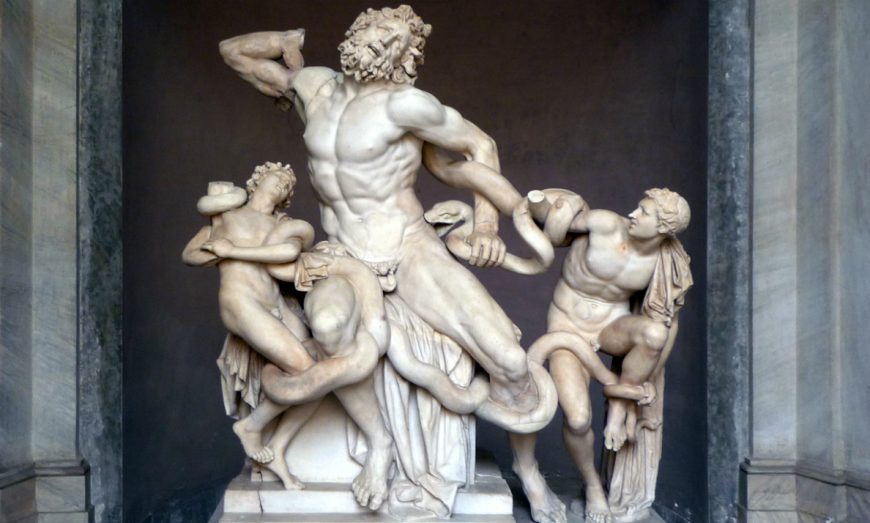

Of the many mythological stories that the ancient Greeks repeatedly told and represented, some of the most popular revolved around the labors of the hero Herakles. After committing a brutal crime against his own family, Herakles worked to make amends for his misdeed by completing 12 seemingly impossible labors that proved his superhuman strength and endurance. In one of these labors, Herakles had to steal several golden apples from a garden in a faraway land. This garden was known as the Garden of the Hesperides, named for the nymphs who cared for it. When Herakles finally arrived at the distant garden, he came across the Titan named Atlas, father of the Hesperides, who was condemned to hold up the heavens for all eternity. Knowing that it would be easier for Atlas to obtain the apples from his daughters’ garden than it would be for him to steal the golden fruits, Herakles convinced Atlas to retrieve the apples. In exchange for Atlas’s help, Herakles agreed to hold up the sky for him. This relief shows the moment that Atlas returned from the garden with the golden apples in his hands. As Herakles’s patron goddess Athena looks on, Atlas offers the apples to the hero, who carries the heavens on his shoulders.

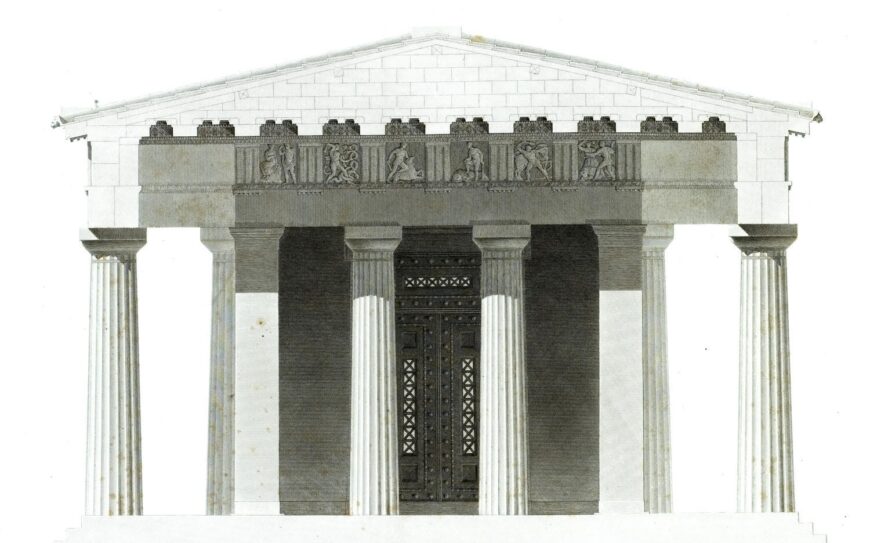

Restored cross section of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia showing the position of the metopes above the porch, by Guillaume-Abel Blouet and Achille Poirot, c. 1831

This relief sculpture is a metope. Metopes are square panels that alternate with triglyphs on buildings that conform to the Doric order. This particular metope was originally positioned high up on the east (front) side of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. It was 1 of 12 metopes carved in relief that showed the different Labors of Herakles to visitors who saw the temple located in the sanctuary at Olympia. You can read more about the metopes, and the temple on which they originally appeared, in this essay about the Temple of Zeus. Here, we will consider this single metope separately as an embodiment of the Severe Style, a representational style that was especially popular in the Greek Early Classical period, which spans from 480–450 B.C.E.

Athena’s face (detail), east metope 4 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The most important traits of the Severe Style can be seen in this metope from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The style gets its name from its simplicity and seriousness, as well as a certain heaviness that characterizes many of its images. This heaviness is apparent in human figures’ faces and clothing. Here, we can see that Athena’s face is fleshy, with a rounded chin and flat cheeks. Her eyelids are thick. Her hair sits heavily on her head, almost like a hat, and is combed in wide waves. Her calm, serious expression is also typical of the Severe style.

The Kritios Boy’s head (detail), 480 B.C.E., marble (Acropolis Museum, Athens; photo: Marsyas, CC BY-SA 2.5)

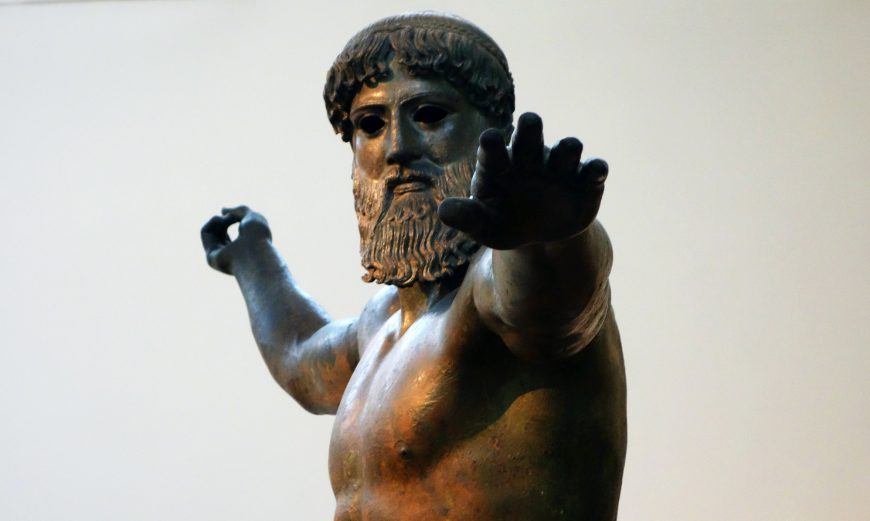

These same characteristics can be seen in other important Early Classical Greek sculptures, including freestanding statues like the Kritios Boy. Like Athena, the Kritios Boy has a heavy chin, full lips, and thick eyelids. His eyes, which are now missing, would originally have been inlaid with another material, perhaps glass. His hair also sits heavily on his head and is carefully combed, with individual strands visible. Although the Kritios Boy served a different function than the metope—he was probably dedicated as a votive offering, and was not used as a temple decoration—the two images share the same distinctive Severe Style.

Athena’s drapery is also typical of the Severe Style. Her dress falls in thick, wide folds. Even though her garment is made of stone, it seems to carry believable weight, falling heavily against her body. This drapery is so thick that it looks almost like pastry dough. This explains why scholars refer to Severe Style drapery as “doughy.” [1]

Another distinctive aspect of Early Classical style is apparent in Athena’s posture. Beneath her dress, we can see that her right knee is visible, as if she is bending her right leg. Her left leg is straight, and she appears to carry all her weight on it. This shifting posture imbues the goddess with life. It is an early version of the contrapposto posture that became popular in Greek sculpture during the Classical period. Figures who stand in contrapposto carry all their weight on one leg, and their hips and shoulders shift in response to this. The contrapposto posture thus shows humans in natural stances, believably bearing the weight of their bodies.

Left: Peplos Kore, c. 530 B.C.E., marble, 1.18 m high (Acropolis Museum, Athens; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Athena (detail), east metope 4 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble, 1.6 m high (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The innovation in Athena’s pose becomes more obvious when we compare her to a statue made during the Archaic period, which directly preceded the Early Classical period. The Peplos Kore is a freestanding statue of a young woman that was likely once dedicated as a votive offering, just like the Kritios Boy. However, unlike Athena on the Early Classical metope, the Archaic figure wears a garment that has only a few thin folds in its skirt. There is no suggestion that her legs are moving beneath her dress: unlike Athena, she stands still. Her stiff posture and rigidity are typical of the Archaic period, which contrasts starkly with the increased movement we find in Early Classical sculptures like the metope from Olympia. The Archaic Peplos Kore’s face is also less heavy and less severe than the Early Classical Athena’s, instead shown with the slight smile that we often find on the faces of Archaic sculptures.

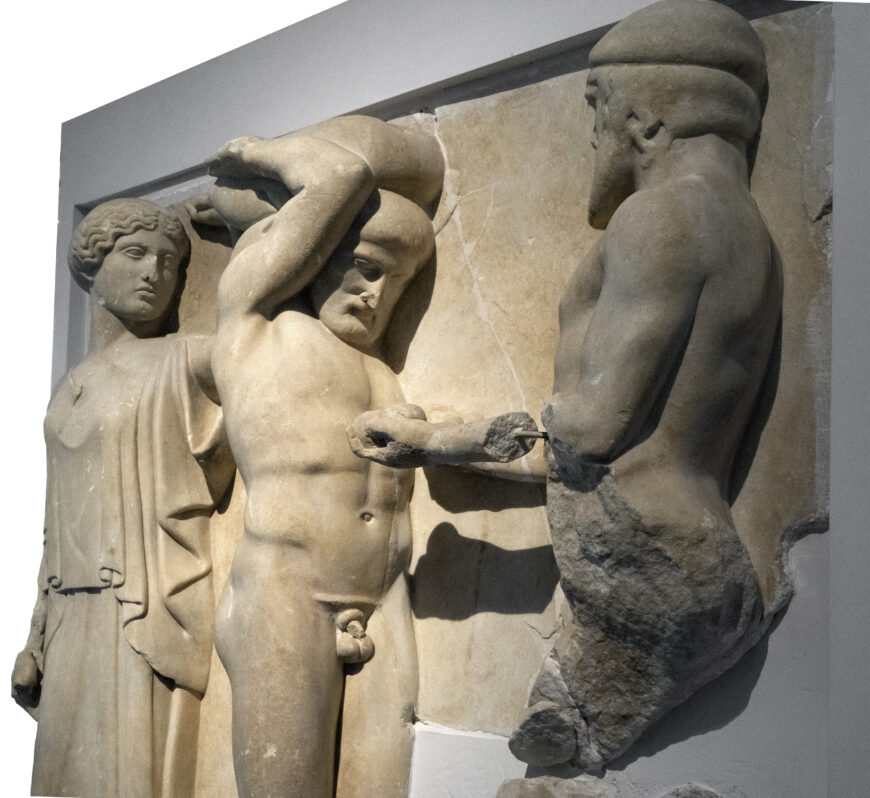

Athena, Herakles and Atlas (detail), east metope 4 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Early Classical interest in naturalism is also evident in the “psychological drama” of the scene in the metope. [2] Although the overall mood of the scene is solemn, its sculptor does show some interest in displaying the characters’ internal states. [3] Athena is calm and solemn. She does not show any signs of struggle or effort as she puts one hand up against the sky, helping her favorite hero Herakles with an ease we might expect from a powerful goddess. Her casual posture and placid expression emphasize her divine strength. By contrast, Herakles’s posture shows how heavy the heavens truly are. Even though he has a cushion behind his neck to help him bear the burden, his head is bowed, and he uses both arms to bear the weight. All of the muscles in his idealized body are engaged as he holds up the sky. His expression is calm, but his posture reveals the seriousness of his struggle.

Athena, Herakles and Atlas from the side (detail), east metope 4 from the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 470–457 B.C.E., marble (Archaeological Museum of Olympia; photo: Egisto Sani, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

To ensure that all visitors to the Temple of Zeus at Olympia would be able to clearly see the image he made, the sculptor carved his metope especially deeply, a feature we can see when we look at the relief from the side. Athena, Herakles, and Atlas are still attached to the panel of marble they are carved from, but they are in very high, or deep, relief. Herakles’s left side is fused to the background, but the rest of his body stands out. Such deep relief carving would have made these figures more visible to Early Classical viewers, who stood on the ground and looked up at the metope where it appeared on the temple. Like many ancient Greek sculptures, this metope also would have been brightly painted when it was first made, further ensuring that it was visible to viewers below.

The sculptor who crafted this metope for the Temple of Zeus at Olympia used the Severe Style to tell an important story from the life of Herakles in a clear, legible manner. Although the figures are idealized, they are also realistic. Their muscles appear to move beneath their skin, even though they are carved of stone. Athena’s shifting stance further imbues her with life. The characters’ expressions are solemn, but their postures reveal more about their emotional states. Standing out from the background in high relief, the figures on this metope would have been instantly recognizable to the ancient Greeks, who would see a story of great heroism and triumph.