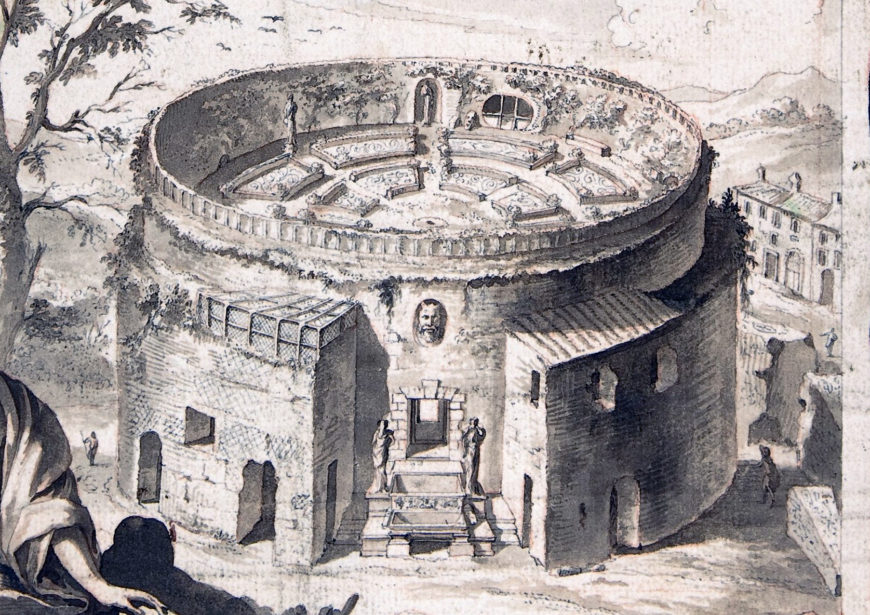

View of the Tomb of Eurysaces, with the Porta Praenestina behind, from the southeast (photo: AncientDigitalMaps, CC BY-NC 2.0)

While pursuing a graduate degree in Library Science at the University of Maryland, Rosie Grant visited cemeteries in search of gravestones that recorded treasured family recipes. In what would become viral videos on social media, Grant recorded her visits, tested the recipes, and presented the results at gravesites. [1] It was a fitting tribute to the deceased whose memory lives on through their most cherished dishes. Although gravestone recipes are a relatively recent phenomenon in funerary commemoration, the desire to memorialize one’s life achievements at a burial site, even in the realm of baking, is not. Such is the case with the funerary monument of Eurysaces in Rome, commonly known as the Tomb of the Baker.

Location, location, location

Everything we know about Eurysaces and his baking enterprise comes from his tomb monument, which is not only one of the best-preserved examples of non-elite funerary architecture in Rome but also includes one of the earliest and most detailed depictions of labor in Roman art. The monument is generally dated to 30–20 B.C.E. It is exceptionally well-preserved, with three of its original four façades remaining largely intact thanks to the construction of the Aurelian Walls in 271 C.E., which entirely enclosed the tomb until 1838 when it was liberated by excavation and demolition works.

Eurysaces’ tomb can be found where two important ancient roads, the Via Labicana and the Via Praenestina, meet and lead into the city of Rome. Rising approximately 33 feet (about 10 meters) above the original ground level, the tomb today is framed by the much larger Porta Praenestina (now known as the Porta Maggiore), which was built in 52 C.E. during Emperor Claudius’ reign to carry above it two major aqueducts (the Aqua Claudia and the Anio Novus). While the tomb’s trapezoidal shape may seem odd at first glance, this form takes advantage of the limited space that remained available between the two roads. It was an area just outside city limits that was once filled with funerary monuments since adult burials were forbidden within the sacred boundaries of Rome. Visibility was clearly imperative to Eurysaces—it would have been impossible for individuals leaving or coming into the city along these major thoroughfares to miss his monument.

Designing a statement piece

Aside from its dominant presence, the tomb would have been distinct from other monuments in the area thanks to its unique combination of materials and unconventional decorative program, which is repeated on all three surviving sides. The structure is composed mainly of travertine slabs around a concrete core with tuff aggregate. The corners are fixed with undecorated engaged pilasters topped by Corinthianizing capitals.

Tomb of the Baker M. Vergileus Eurysaces (part of the William L. MacDonald Collection, Princeton University)

At the bottom is an undecorated socle, which supports a middle register of long, vertical cylinders. Above this, a thin band bearing an inscription in Latin reads:

EST HOC MONIMENTUM MARGEI [sic] VERGILEI EURYSACIS PISTORIS REDEMPTORIS APPARET

This is the monument of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, baker, contractor, public servant[2]

Moving upward, another register is inset by three rows of hollow, tube-like features roughly the same size as the vertical cylinders below. Finally, a figural frieze that shows various stages of breadmaking wraps around the top of the monument, which is then surmounted by a cornice.

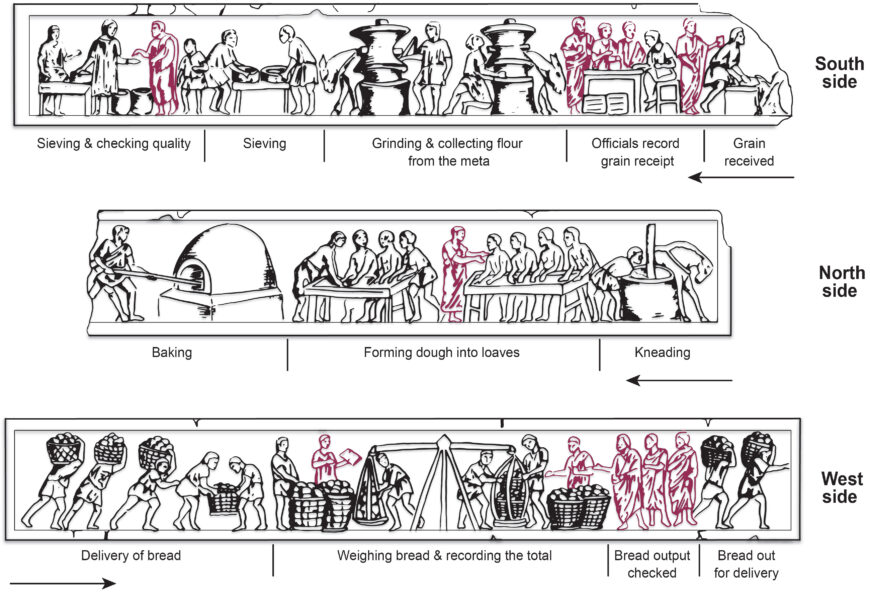

Line drawing of the south, north, and west sides of the frieze. Figures in togas are highlighted in purple (image by A. B. Kidd, adapted from Curtis, Ancient Food Technology, 2001, p. 359)

View of the south side, View of the Tomb of Eurysaces, with the Porta Praenestina behind, from the southeast (photo: Jamie Heath, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Although the east side of the monument no longer remains, the frieze’s narrative appears to begin on the south side of the structure with the delivery of grain to a workshop. Reading from right to left, the scene depicts the receipt and recording of grain before it is ground into flour using a donkey-powered mill. The grounds are then sieved and inspected for quality. From there, the narrative intriguingly continues not on the west side but on the north side, again from right to left, where a horse-driven kneading machine is depicted, followed by the shaping of dough before baking it in an oven. Although the left-most end of the northern frieze is not fully preserved, the narrative picks up on the west side, where the bread is transported in baskets, weighed and recorded before being carried away. The frieze’s exceptional detail surpasses any description provided in the ancient literary record about baking procedures.

The knead for speed

Considering the specificity of the narrative and the inscription, in which Eurysaces proudly identifies himself as a pistor (baker), it is evident that the elusive cylindrical shapes on the monument’s façade must be connected to breadmaking. However, scholars have long debated their form and meaning. Some believe that these cylinders depict grain measures, storage containers, or even vents of an oven, but it is generally agreed that they represent mechanical kneading machines like that illustrated in the frieze. Such devices have been archaeologically attested in Roman cities like Pompeii and Ostia, where the evidence confirms that their shape looked very much like those depicted on Eurysaces’ monument.

Further evidence is provided within the hollow shapes themselves, where small, square recesses discolored by rust can be found in the back of each. These were likely used to mount a projecting device that would have been necessary for turning the dough but is no longer preserved on the monument. At the time that the monument was erected, mechanical kneading devices were a relatively new development. It is thus likely that Eurysaces was especially excited to show off his adoption of this novel technology, which would have made baking on a large scale more efficient.

Plausibly Eurysaces and Atistia, found in excavations near the Tomb of Eurysaces (photo: Jamie Heath, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Eurysaces’ other half

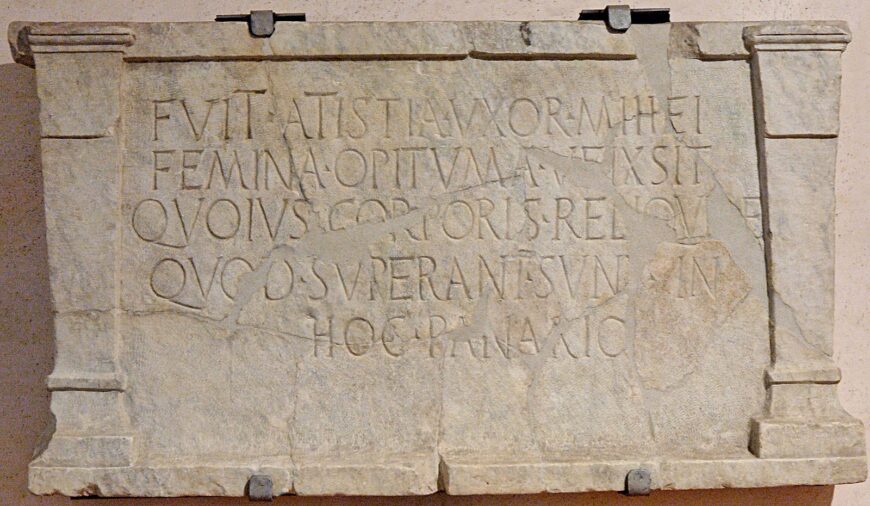

We can only speculate about what the monument’s east side would have once displayed. In 1838, during the demolition of the walls that once encased the monument, a relief sculpture in marble depicting a man and a woman was discovered. The man wears a tunic and toga and the woman wears a tunic and palla, both the dress of Roman citizens with high social status. Their position, turned slightly towards each other, suggests that they were married. The excavations also produced an inscription, again in marble, reading:

FUIT ATISTIA UXOR MIHEI

FEMINA OPITUMA VEIXSIT

QUOIUS CORPORIS RELIQUIAE

QUOD SUPERANT SUNT IN

HOC PANARIO

Atistia was my wife

She lived the life of an excellent woman

what’s left of her body is in

this breadbasket[3]

Atistia’s epitaph, found in excavations near the Tomb of Eurysaces (photo: public domain)

No clear evidence connects either the relief sculpture or the inscription to Eurysaces’ monument, except for the last line of Atistia’s epitaph, which mentions a breadbasket. Intriguingly, a breadbasket-shaped urn sculpted in marble was found nearby, and it is tempting to connect all three elements to Eurysaces. [4] Even so, it is important to remember that these elements were all made from marble, whereas most of Eurysaces’ monument was sculpted from travertine. What is more, in the area surrounding this tomb, six epitaphs of other pistores (bakers) have been found, including one of a female baker (a pistrix), all dated to the end of the 1st century B.C.E.—the same period in which Eurysaces erected his monument. [5] Eurysaces’ monument, however, is certainly the most sumptuous of these, and of all of these bakers it is Eurysaces who would have been the one most capable of affording the more expensive commission in marble.

Not just any baker

So what are we to make of Eurysaces from all of this? To start, we can look at his very name, which is Greek in origin. Whereas it is unsurprising to find that Greeks were living in the city of Rome in the late 1st century B.C.E., the fact that Eurysaces does not name his lineage (declaring himself as “the son of…”) suggests that Eurysaces had once been enslaved but gained his freedom as a libertus (literally “freedman’”) at some point through his professional successes as a baker. Such an interpretation would certainly account for the funerary monument’s focus on baking. It would also fit well with Eurysaces’ role as a redemptor, or state contractor, as he claims on his inscription.

It was quite common for highly skilled enslaved individuals to be granted their freedom and gain Roman citizenship but continue working professionally for their former owners. If Eurysaces had once been owned by the emperor at the time, Augustus, or at least someone in the emperor’s elite inner circle, it would make sense that he would go on to work as a contractor overseeing baking enterprises for the state. It was under Augustus’ direction that the state offered free rations of bread to the citizens of Rome. Eurysaces’ plausible role in this endeavor would also explain why he refers to himself as a public servant in his epitaph.

Figural frieze, north side (detail). A togate figure oversees bare-chested workers kneading dough (photo: William L. MacDonald Collection, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University)

Further support for Eurysaces’ role can be found in the monument’s narrative frieze, which preserves at least 31 depictions of workers clad in either short tunics or shown bare-chested and 11 officials, identifiable by the togas they wear and the record logs that they wield. Taken as a whole, the frieze emphasizes the quality and quantity inspections before and after each stage in the breadmaking process rather than the work being completed in the bakery—just the sort of inspections that a state contractor would be expected to undertake. Although it is impossible to identify Eurysaces specifically as one of the toga-clad figures in the scenes, it is clear that we are looking at a massive enterprise of baking, taking place on an industrial scale and closely monitored by state representatives.

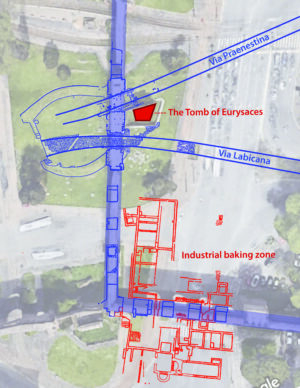

Archaeological remains uncovered near the Porta Praenestina. In red, the Tomb of Eurysaces and a large-scale milling complex. In blue, the main roads (Via Praenestina, Via Labicana), the city gate (Porta Praenestina), and the aqueducts (Aqua Claudia, Anio Novus). Line drawing overlaying GoogleMaps image by A. B. Kidd, adapted from Coates-Stephens 2004: Plate I (G. Ioppolo, SOVRCBAS)

One place where such an enterprise took place can be found just south of Eurysaces’ tomb. There, a large-scale milling complex was discovered during archaeological investigations of the area in 1838–42 and 1954–56. This complex featured two large halls and in its immediate vicinity at least seven animal-powered mills, several grinding stones, basins, and storage vessels (also known as dolia) were unearthed. The complex appears to have been in use by at least the mid-1st century B.C.E., around the same time that Eurysaces’ tomb was built, and was in operation until 52 C.E. when it was destroyed to make way for the construction of the two new aqueducts which ran through the area. Although no ovens were documented during these excavations, the discovery of a flour mill and the funerary inscriptions of at least six other bakers in the area, all broadly dated to the same period, can hardly be a coincidence.

A true monumentum

In Latin, the term for a monument, monumentum, derives from the verb monere, which means “to remind, to bring to the notice of.” When applied to Eurysaces’ tomb, it is evident that every part of his sepulcher was conceived as a monumentum, declaring to all individuals who passed through Rome’s busy city gate who he was and how he expected to be remembered. Eurysaces thus tells us that he was more than a craftsperson; he was an astute and accomplished businessman who rose from slavery to the highest levels of social status that were attainable. Although he was not a member of the aristocracy, he emulated their style and commanded a public presence. Much like the recipe gravestones that can be found in today’s cemeteries, Eurysaces’ monument stands as a testament to his professional successes and memorializes his life achievements through baking.