the making, the modeling of our first mother-father, with yellow corn, white corn alone for the flesh, food alone for the human legs and arms…The Popol Vuh

So goes the Quiché Maya creation story recorded in the Popol Vuh. The myth recounts that the creator gods made four attempts at constructing humanity: first from animal parts, then mud, followed by wood, and finally, corn. With corn they were ultimately successful, indicating corn’s importance not only as sustenance, but also as symbolically charged with life force.

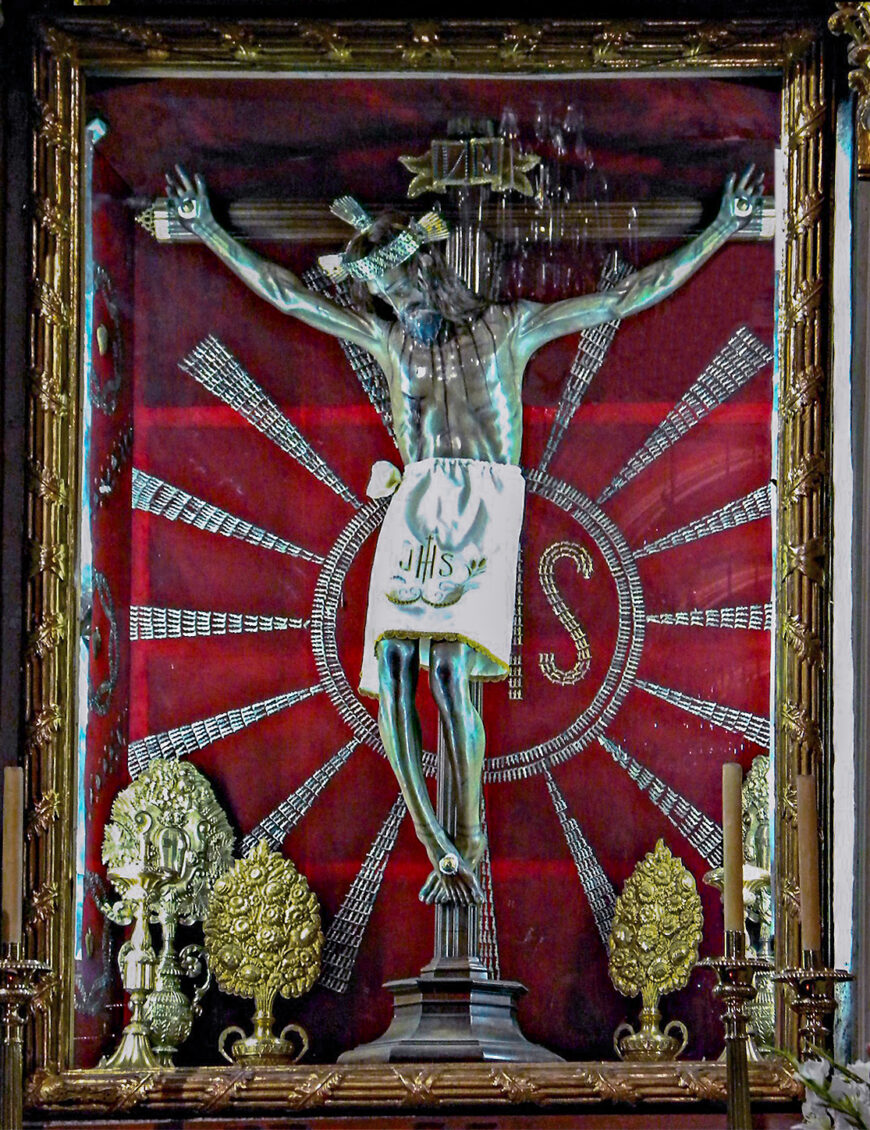

Crucifix of the Señor de la Sacristía, 16th century, polychromed corn pith, Cathedral of Morelia, Michoacán, México (author’s photo, all right reserved)

Corn pith sculptures, pasta de caña

Corn was a staple crop of Mesoamerica, and was widely laden with sacred symbolism associated with creation. Indigenous artists not only sculpted images of the corn god, but also modeled objects out of corn using stalk fibers mixed with orchid glue into a paste. [1] Sadly, pre-hispanic corn sculptures using this method do not survive, but this same Indigenous technology (often likened to papier-mâché), was used extensively for Christian religious sculpture in the early colonial period (primarily the 16th century). In fact, the cristos de caña are emblematic of emerging Indigenous Christianity.

Franciscan missionary Gerónimo de Mendieta wrote of the corn pith sculptures, called pasta de caña, in his chronicle Historia Ecclesiástica Indiana: “They also carry crucifixes made from reeds that are the size of a large man but weigh as little as a child.” [2] Similar (but much heavier), sculptures made of wood were common in the Spanish world. They were made with a polychroming encarnación technique known for making saints and holy figures appear remarkably life-like. However, the pasta de caña technology allowed for much lighter sculptures—making them far more appealing as processional objects.

Take, for example, the 16th-century crucifix of the Señor de la Sacristía, housed in the Cathedral of Morelia, Michoacán. Made of pasta de caña, the figure features copious blood flowing from Christ’s wounds, thereby emphasizing his human suffering. The sculpture is venerated in July, when historically it was carried in procession. This time of year corresponds with the pre-hispanic P’uhrépecha month of Caheri Cascuaro, or “Great feast of Lords.” This celebration of lordship in the Indigenous context likely paralleled the veneration of Christ as lord in the new, Christianized, context. Additionally, this month was associated with planting and immature corn stalks, furthering the associations between the local cristo de caña and Indigenous concepts surrounding the sacrality of corn. [3]

Religious processions like the ones held in Michoacán, were most famously enacted during Semana Santa (Holy Week). Still practiced today in many towns and cities in Latin America, typically these public processions would bring together people from all walks of life to witness the spectacle of those marching in the parade in fine clothing and bearing various sacred and liturgical objects. Often organized by confraternity members, the processions were multiethnic, public declarations of piety and social standing. It was for this context specifically that the pasta de caña sculptures, oftentimes images of Jesus Christ (cristos de caña), were made.

Pre-hispanic codices inside

The cristos de caña were modeled with a reed framework upon which the corn pith mixed with gum was modeled into a naturalistic body. Paper was also sometimes inserted into the matrix of the objects, and recent x-ray studies have revealed the placement of pre-hispanic codices (books) within the inner layers. [4]

As corn was a sacred Indigenous substance and the ancient books were prestige items, scholars have speculated that the sacred nature and worth of the materials that made up the statues may have added to their meaning in the eyes of Indigenous converts by linking them to the pre-hispanic past.

The development of these processional sculptures has been credited to the bishop of Michoacán, Don Vasco de Quiroga. Known as a “protector of Indians,” the bishop advocated against Indigenous enslavement, insisting that Natives be organized into administrative congregations for the purposes of Hispanization and conversion. He was inspired by Sir Thomas More’s Utopia which imagined a land where people worked communally, governed by order and discipline. As bishop, Quiroga named the city of Pátzcuaro the capital of the diocese. There he founded the Seminary of San Nicolás, where the local P’uhrépecha population were taught Christian religion, government, and craftsmanship.

While the cristos de caña likely held Indigenous associations for the locals who made and used them, their association with Indigenous practices soon became de-contextualized in their use in churches throughout Mexico as well as in places as far away as Spain and the Canary Islands. While as scholars today we may be tempted to refer to the cristos de caña as hybrid objects for their merging of Indigenous technologies with Christian iconography, it is important as well to recognize that these ideas may not always have been relevant to the period in which they were made. The technology, producing lightweight and naturalistic bodies, suited itself well for the processional and devotional practices of the Spanish colonial world, revealing that Indigenous peoples, far from passive receptors of Spanish culture, left their mark, both seen and unseen.