Obelisks, Mestre Valentim, Passeio Público, Rio de Janeiro, begun 1779, inaugurated 1783 (photo: Rodrigojordy, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In the middle of the eighteenth century a series of epidemics ravaged the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The illness was attributed to the unsanitary air caused by human and animal waste in Lake Boqueirão. The viceroy Luis de Vasconcelos e Sousa ordered the lake to be filled in and a public park, the Passeio Público (public promenade), to be erected in its place. The park’s purpose—to beautify the city and provide a healthy space for outdoor leisure—was suggested by the inscriptions written on two obelisks, “the longing for Rio,” and “the love of the public.”

The Passeio Público represented several groundbreaking achievements: the first public park on Brazilian soil, some of the first large-scale bronze sculptures cast in Rio de Janeiro, and a major urban planning commission awarded to an artist of African descent.

Karl Wilhelm von Theremin, “The entrance of the Passeio Público,” in Saudades do Rio de Janeiro, 1835, lithograph and watercolor, 48 x 30.5 cm (Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro)

Valentim da Fonseca e Silva, better known as Mestre Valentim (Master Valentim), was born around 1745 in the diamond mining region of Brazil (Serro do Frio, Minas Gerais). His parents were Manoel da Fonseca e Silva, a wealthy Portuguese man, and Amatilde da Fonseca, a woman of African descent. The earliest known account of Valentim’s life states that the artist traveled with his family to Portugal as a baby and received an education there before returning to Brazil. While this story about his youth has not been verified with documentary evidence, Valentim arrived in Rio de Janeiro as a young man and worked there for the rest of his life. Although Valentim described himself as a carver, he was one of the viceroy’s favorite architects and received numerous important commissions.

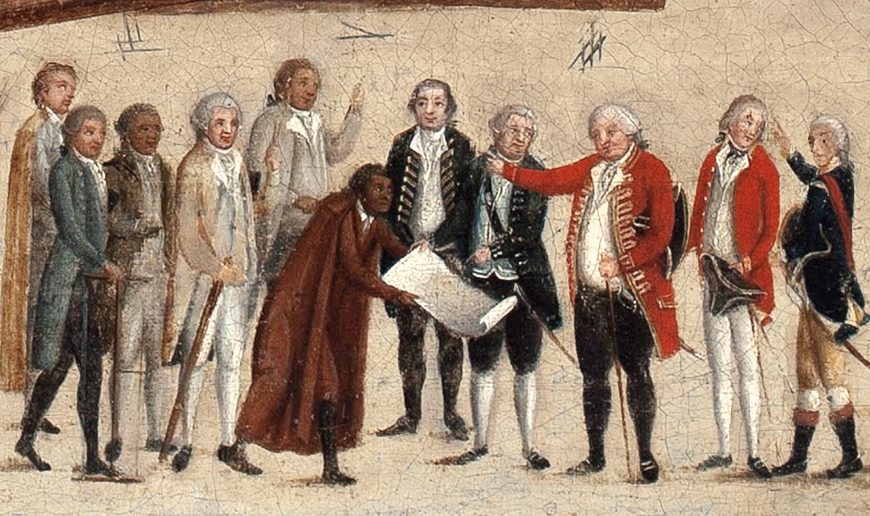

Detail, João Francisco Muzzi, Joyful and quick rebuilding of the church of the old Monastery of Nossa Senhora do Parto, 1789 (Museu do Açude, Rio de Janeiro)

A painting commemorating the destruction of a convent portrays Mestre Valentim presenting the plans for the building’s replacement to the viceroy and other officials. At a time when portraiture was rare in Brazil, this detail was probably included because a black architect was seen as a novelty. The painting highlights Valentim’s dark skin and his humility as he bows down before the well-dressed officials.

Brazil’s first public park

Large portions of the city of Lisbon, Portugal—the capital of the empire—were destroyed by earthquake and the resulting fires in 1755, prompting a rebuilding campaign. Enlightenment ideals of producing a beautiful and hygienic city with fresh air, clean water, regular streets, and public parks guided the redesign of the city. These same ideals prompted the construction of the Passeio Público in the colonial city Rio de Janeiro. At the same time that the Marquis of Pombal worked to revitalize infrastructure and industry throughout Portugal, the viceroy in Rio de Janeiro (the capital of Brazil) embarked on an ambitious campaign to modernize the city, leading to numerous building campaigns, increased access to clean water, and technological advancements, such as securing the tools, resources, and knowledge needed for making large bronze sculptures.

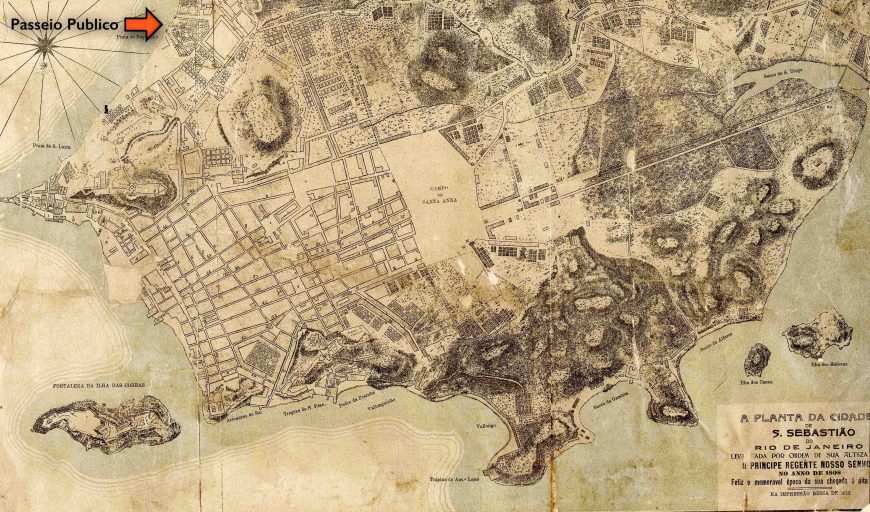

A plan of the city of S. Sebastian of Rio de Janeiro…in the year 1808, printed 1812 (Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro).

Mestre Valentim designed a trapezoidal park with the narrow end overlooking the bay, reminiscent of baroque and rococo palace gardens such as that of Queluz outside of Lisbon. Such gardens were often organized into a series of intersecting geometric shapes.

Queluz palace and gardens, Portugal (photo: Jean-Christophe Benoist, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The walkways at 18th century gardens such as Queluz directed the movement of visitors between carefully arranged plots of land ornamented with plants and sculptures. Elaborate fountains formed centerpieces at the main intersections of the walkways.

Pavilions in the passeio público

In the Passeio Público, two square pavilions originally flanked the terrace overlooking the water. Sadly, today, little of Mestre Valentim’s design remains. The park was altered on numerous occasions throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Few of Valentim’s sculptures remain in their original locations, the pavilions were first modified into octagonal structures and then eliminated altogether, and the geometric arrangement of the walkways and plants has been entirely replaced with undulating, irregular forms.

Leandro Joaquim, Whale fishing, late 18th century oil on canvas (Museu Histórico Nacional, Rio de Janeiro)

The pavilions contained whimsical displays celebrating the natural resources of Brazil and Rio de Janeiro. The interior of one pavilion was covered in ornaments made of shell, including sculptures of local fish. This pavilion housed Leandro Joaquim’s series of paintings of the Rio de Janeiro harbor (now in the Museu Histórico Nacional and Museu Nacional das Belas Artes). These oval paintings highlighted the viceroy’s improvements to the city, such as the aqueduct and a large plaza, and the beneficial industries that were conducted on the waterfront, such as fishing and transoceanic trade.

The other pavilion was decorated with sculptures of local birds made of feathers. This pavilion contained a series of paintings (now lost) depicting what were considered Brazil’s most important industries: gold, diamonds, sugar, and other agricultural products. The celebration of Brazil’s natural resources continued in the sculptures that decorated the park, such as the intertwined caimans featured on one of the fountains. While European travelers typically viewed tropical plants and animals as symbols of strange and backward lands, the Passeio Público celebrated Rio de Janeiro as both tropical and industrious.

Mestre Valentim, Alligators Fountain, 1783 (photo: Rio de Janeiro Department of Conservation)

The passeio público provided visitors with a venue for various forms of entertainment such as operas, concerts, plays, and festivals honoring the Portuguese royal family. Spending leisure time outdoors was viewed as essential to the physical and mental well-being of the city’s wealthy inhabitants.

One of the park’s fountains highlights the importance of pleasure with a sculpture of a nude boy holding a placard that states “I am useful even while playing.” Valentim injected playfulness into his otherwise orderly and controlled environment with the juxtaposition of the natural and the man-made. For example, he placed a papaya tree next to a painted bronze sculpture of the same plant. The shell and feather interior decorations of the pavilions also allowed visitors to delight in comparing the natural and the artificial.