36 of 96 feather panels, Wari, c. 600–900 C.E., feathers on cotton, camelid hair, South Coast, Peru, 207 x 614 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

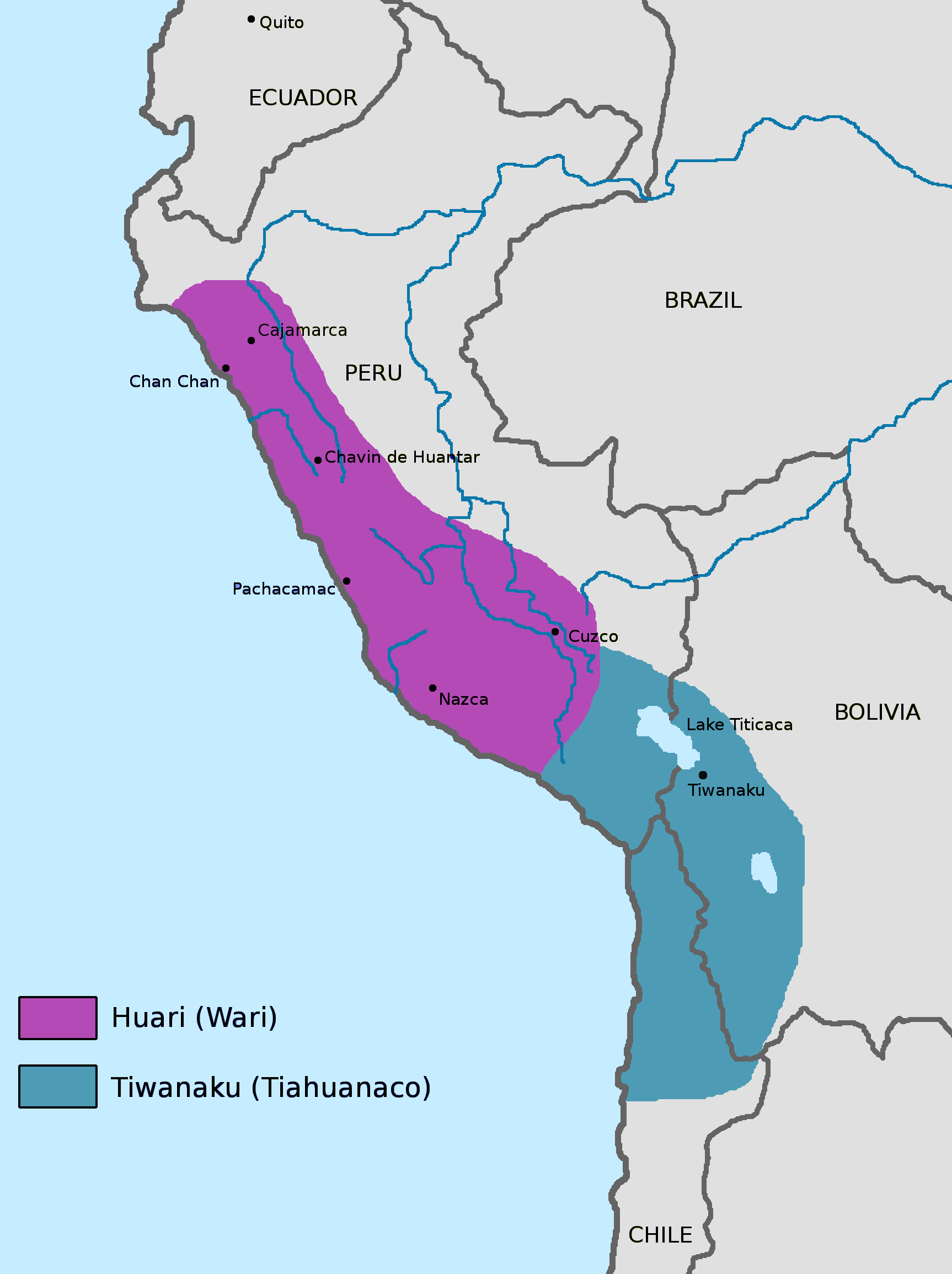

Map of Wari and Tiwanaku civilizations, South America. Wari civilization about the same time as Tiwanaku (image: Zenyu, in the public domain)

Blue and yellow horizontal rectangles, shimmering the way only natural feathers can, alternate in a stunning iridescent abstraction. The 96 panels (today split apart into different sections) are composed of two yellow and two blue rectangles made up of tens of thousands of macaw feathers.

The panels were made by the Wari culture, an empire that stretched from the mountain highlands to the southern coastal region of what is now Peru during the Andean Middle Horizon period, c. 600 to 900 C.E.

The panels were found in the Churunga Valley on the far south coast, and they are composed of feathers from the blue and yellow macaw, a bird found in the Amazon rainforest along the eastern slopes of the Andes mountains, some 500 miles (approximately 806 kilometers) away from the valley. The panels continue an earlier Andean tradition of extraordinary featherwork, demonstrating Wari artists’ excellence in conceptualizing abstract designs and their advanced skills in featherwork, a type of art so delicate and fine it is often called feather painting.

Feather panels, Wari, c. 600–900 C.E., feathers on cotton, camelid hair, South Coast, Peru, 207 x 614 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The discovery

In 1943, farmers from the village of La Victoria discovered a cache of buried items, including the series of 96 feather panels. The feather panels had been rolled and placed into eight large (one by two meter) ceramic jars painted with faces and abstract designs, then buried in a mound of earth and stone and surrounded by concentric walls. The fragile feathers and their ceramic jars were, fortunately, well-preserved within the dry earth. Silver, gold, ceramics, and other luxury objects were also found.

Without a well-documented excavation by trained archeologists and art historians, key information about the nature of the site and its contents was lost, and there was no written text to accompany the materials. By some accounts, buried bodies were also unearthed, but they were immediately burned and destroyed by the locals who believed they possessed the power to cause harm if disturbed. [1] In some Andean cultures, mummies were included in complex burials. In other areas, buried bodies were naturally preserved by the conditions of the climate, a process that may have been understood and anticipated. Whether or not bodies were buried with the jars remains uncertain. When they were discovered, the panels were much admired for their beauty and craftsmanship, and soon caught the attention of Peruvian archeologists who collected and distributed them to museum collections.

Feather panels, Wari, c. 600–900 C.E., feathers on cotton, camelid hair, South Coast, Peru, 207 x 614 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Why were the panels made?

Various interpretations about the panels’ functions in Wari culture have been proposed by scholars based on what we know about the Andean worldview. One key concept is the belief in a supernatural realm that should be honored with elaborate art and luxury goods, some of which were made only to be buried as offerings. A widespread belief in the afterlife also led to the inclusion of luxury goods as part of (presumably) elite burials. The panels’ burial context suggests that they may have been offerings meant for the spirit world, accessories of an elite tomb meant to accompany one or more individuals, or perhaps both.

Another possibility is that the panels were part of a ceremony that involved the living. Andean cultures often engaged in rituals as part of their spiritual practices. These events would have required enhancement with art, such as featherwork, in order to elevate them beyond everyday experiences. The panels might also have decorated and defined a sacred site, known in the Andes as a huaca. Huacas could be places (springs or other water sources, rock formations), human-made or natural objects in the landscape, or even people. A site identified as a huaca was often adorned with art or other identifying markers. The panels’ large size and the presence of braided cords on the corners meant for securing them to a surface suggest that they might have served as artistic enhancement on the walls of a huaca. It has been noted that the later Inka also honored this site as a huaca by placing their own art and artifacts within the burial mound. [2]

The magic of feathers

Humans throughout time and place have valued birds’ feathers for their attractiveness and have gone to extraordinary lengths to acquire them. In the Americas, birds and feathers had a sacred role in addition to their value as objects of beauty. The unparalleled splendor of natural feathers, never duplicated by artificial means (even in the era of synthetic manufacturing) was assigned a spiritual value. Prior to the rise of the Wari empire, two earlier cultures of the south coastal region, Paracas and Nasca, established long-range trade networks with the Andean highlands and eastern Amazonian jungle to access feathers for their garments and accessories. While both cultures had largely disintegrated by the time the Wari empire was established on the south coast, remnants of featherworking knowledge remained in the region. Also, the means to acquire them by trade was quickly assimilated by the Wari, whose artists transformed earlier motifs into powerful abstract statements of their own.

Wari abstraction and statecraft

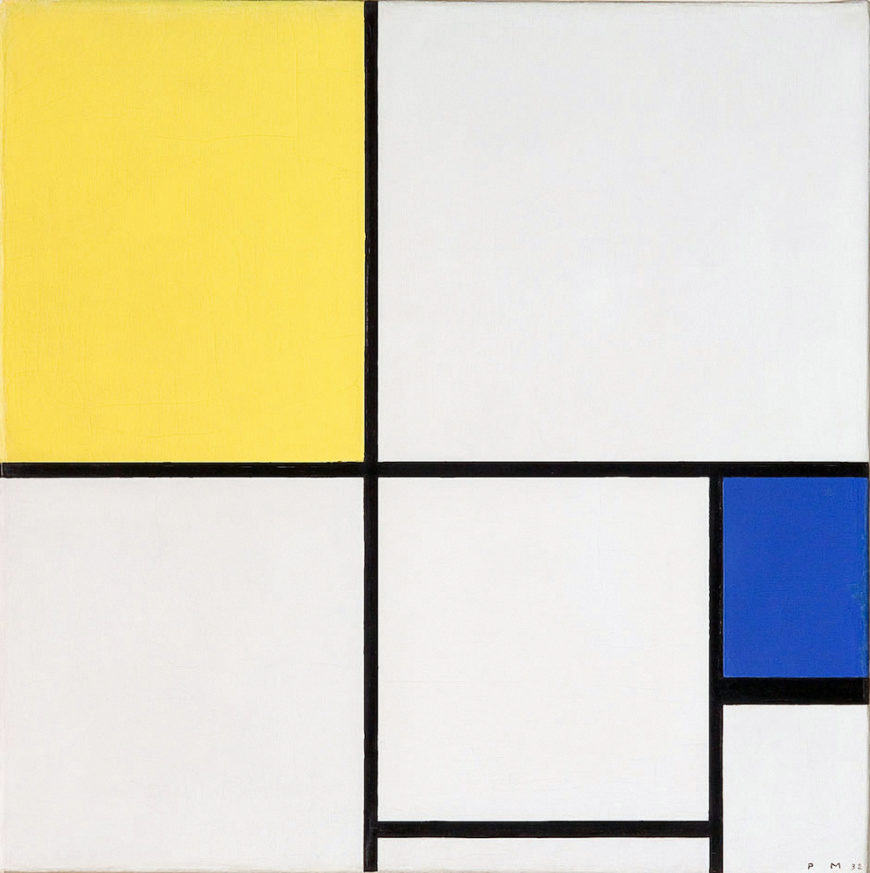

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Yellow and Blue, 1932, oil on canvas, 55,5 x 55,5 cm (Fondation Beyeler, Basel; photo: Lluís Ribes Mateu, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The Wari are known for their complex, abstract designs in woven and featherwork textiles—many Wari motifs appear strikingly similar to modernist expressions of the early 20th century (such as we see in Piet Mondrian’s paintings). The German modernist, Max Ernst, may have owned a section of the panels. Wari textiles surpassed experiments in shape and color, containing layers of cultural meaning that would have been immediately understood by members of their society. In a stratified, imperial system such as the Wari, an elite tunic might convey a statement of power, broadcasting in vividly dyed camelid fibers a wearer’s high social position.

The feather panels would have served a similar function, although as wall hangings rather than personal adornment. The powerful blue and yellow design has been created through the natural colors of the macaw feathers, trimmed, shaped, attached to strings, and sewn in rows onto a cotton and camelid fiber textile in a manner that highlights their intrinsic beauty.

The possible meanings assigned to the colors remain unknown, but due to the Andean attunement to their natural world, it is possible that the panels represent an abstracted south coast landscape of golden sand paired with a blue sea and sky, communicating an elite’s connection with each realm.

The feather panel in context

Feather panels, Wari, c. 600–900 C.E., feathers on cotton, camelid hair, South Coast, Peru, 207 x 614 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This extraordinary series of panels demonstrates the assimilation of earlier featherwork traditions from the southern coastal region and the continuity of the value placed on feathers in this area, as well as exemplifies the Wari abstract art style. One can imagine the drama of the blue and yellow surfaces, shimmering in the intense south coast sun during the day or illuminated at night by flame, transforming a monochromatic desert area into a colorful realm for ritual ceremonies. It is also possible that the feather panels were never meant for human eyes or experience, but only for the afterlife and the realm of the spirits. While speculation about their meaning is ongoing, contemporary audiences can certainly admire the abstract design and technical accomplishment of the Wari feather panels. They are considered to be among the most significant examples of Andean featherwork yet discovered.

Notes:

[1] Heidi King, “The Wari Feathered Panels from Corral Redondo, Churunga Valley: A Re-examination of Context,” Ñawpa Pacha, Journal of Andean Archaeology 33, no. (2013), pp. 25–26.

[2] King, p. 36.

Additional resources

Thor Hanson, Feathers: The Evolution of a Natural Miracle (New York: Basic Books, 2011)

Rebecca Stone, Art of the Andes: From Chavín to Inca (London: Thames & Hudson, 2012)