Flying Figure bowl, 3rd–1st century B.C.E., Paracas, ceramic, post-fired paint, 5.1 x 17.5 x 17.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A flyer and a feline

A smiling figure hangs suspended, staring from a void. On the outside wall of the bowl, cats look out at us. The beings almost have the charm of contemporary children’s book illustrations with their simplified, animated lines and bright colors. These deceptively familiar, even playful figures appear on the interior and side of a ceramic bowl made by the Paracas culture of the first millennium B.C.E. This exceptionally well-preserved ceramic vessel was found in a burial from the Ica Valley, and it illustrates a key Paracan supernatural figure and coastal feline—the pampas cat.

Along the southern coast of Peru, the Paracans fished the rich Pacific Ocean and farmed in small river valleys along the otherwise arid and inhospitable desert coast for about 1,000 years. In this harsh environment, they generated a colorful material culture, a great deal of which was devoted to the afterlife and so survived in underground burial chambers. Burials on the Paracas peninsula and in the nearby river valleys contained mummies bundled in layers of textiles, some of which were brightly colored, embroidered, and accompanied by ceramics and other artifacts. With no written text, the contents of the burials are now the only record of their beliefs and cultural practices.

Flying Figure bowl, 3rd–1st century B.C.E., Paracas, ceramic, post-fired paint, 5.1 × 17.5 × 17.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A painted item for the elite

The images on the ceramic vessel were first incised into the soft clay with shallow cuts. Then, the vessel was fired and painted with vegetal and mineral pigments bound together by heated plant resin, which hardens when cooled (a method called post-fire resin painting). It was not intended for use in daily life because of the way it was painted—it would not have held up to normal wear-and-tear because the plant resin in the paint melts in heat. Paracan ceramic artists also knew and utilized more widespread decorative techniques such as pre-fire slip painting, but the more technically demanding post-fire resin technique added value to the vessel.

This bowl, which has no recorded findspot, was likely among a medley of prestige items (including textiles, gold ornaments, feathers and feather work, spondylus shells, and animal pelts) that would have embellished the mummy bundle and afterlife environment of a high-ranking Paracan individual.

Flying Figure bowl, 3rd–1st century B.C.E., Paracas, ceramic, post-fired paint, 5.1 × 17.5 × 17.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The strange anatomy and accessories of the flying figure

Inside the bowl, the figure (generally identified as a flying figure) appears in red, green, and white paint. Its frontal head has over-sized eyes made of two concentric circles and an upturned mouth resembling a mysterious grin. From the mouth streams a red emanation ending in a stylized head, possibly a serpent head with exaggerated fangs, or a disembodied human head tasted by an elongated tongue. Its green body is shown in profile and has a band along its back ending in a black triangular tail. Three white fingers hold a head by its hair, and the feet are abstracted into sharp triangles. The hand-held head has a closed mouth of one straight line, likely indicating a state of death. The head at the end of the mouth emanation has slightly upturned corners, registering as the hint of a smile. Symbolic heads are a frequent appearance in Paracas art. Some art historians believe the heads represent power and fertility. The black angular tail (and possibly feet) of the flying figure could refer to ceremonial obsidian knives (used in ritual or symbolic decapitation—a practice well-documented in Paracas culture) that have been found in some of their burials.

A curving red band within a yellow border bisects the center of the vessel, possibly indicating the otherworldly realm of the flying figure. A green step motif might represent the Andes mountain range rising abruptly just to the east of the coastal environment. Mountains, widely considered to be a supernatural realm, might be the flyer’s ultimate destination.

Who is the flyer?

The flying figure is likely an entity that archaeologists and art historians have called the Oculate Being, one version of a multi-faceted Paracas supernatural that first appears in early textile art and emerges as a frequent motif in later ceramics. Named by scholars for its overly large eyes, the Oculate Being might be based on the coastal Peruvian burrowing owl. This unusual bird lives in underground desert burrows and, unlike other owl species, emerges during the day as well as night to hunt and forage. The owl’s frontal eyes and atypically long legs give it a slightly anthropomorphic (human-like) appearance. Paracans, too, made their homes in walled, subterranean spaces that offered protection from the harsh desert, and might have been intrigued by this owl whose daily activities paralleled some of their own.

Flying Figure bowl, 3rd–1st century B.C.E., Paracas, ceramic, post-fired paint, 5.1 × 17.5 × 17.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The pampas cat

Pampas cat (photo: ZooPro, CC BY-SA 3.0)

On the bowl’s side, set against the red background, the stylized white feline figure has an upturned mouth and round green eyes. It likely represents a pampas cat. A small wild cat native to South America that frequented coastal river valleys, pampas cats are a common motif in Paracan embroidered textiles, painted ceramics, and they even appear as a late geoglyph (large-scale land art).

In textiles, the feline often appears alongside birds or serpents, as animal companions to humans, part of human-animal hybrids, or is suggested indirectly by feline costumes. Art historian Anne Paul has argued that the border cloth of textile mantles (large, sleeveless wraps found in mummy bundles) and their imagery symbolically protected both the deceased human wrapped within the textile and the images in the center of the cloth. [1] This idea might also apply to Paracas ceramics, with the feline protecting the flying figure within.

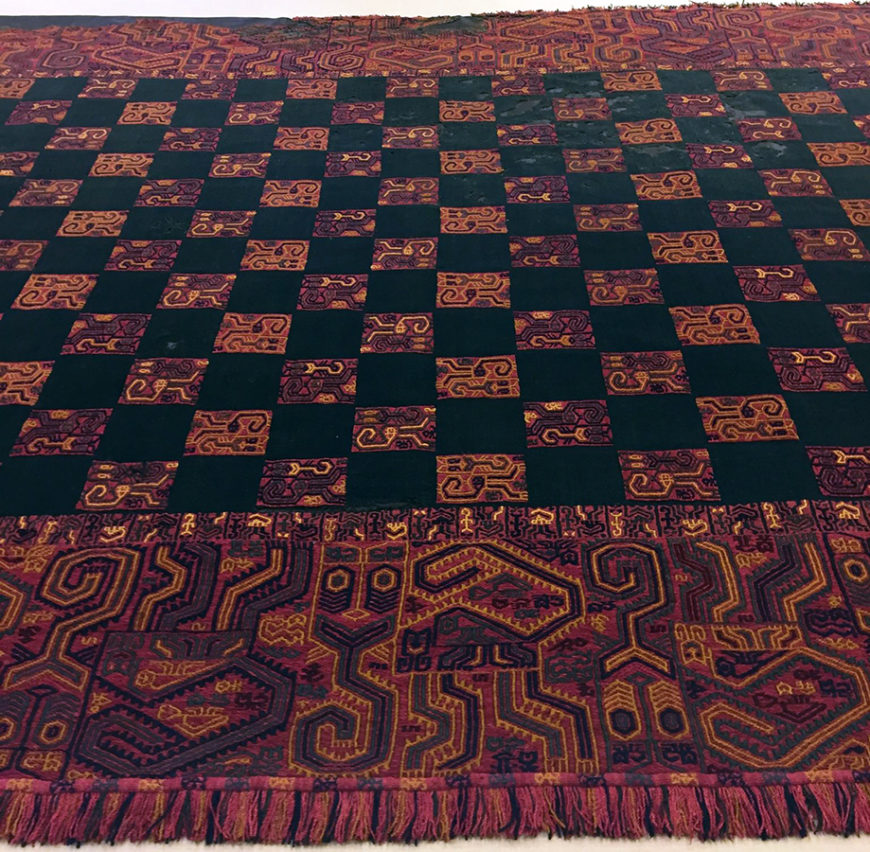

Paracas embroidered mantle, 100 B.C.E.-100 C.E., camelid fiber, 105 1/8 x 51 15/16 inches (267 x 131.9 cm) Brooklyn Museum

The mysterious Paracas flyers

3rd–1st century B.C.E., Paracas, Ceramic, post-fired paint, 5.1 × 17.5 × 17.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Detail, Man’s mantle and two border fragments, Paracas, 50–100 C.E., wool plain weave, embroidered with wool, 101 x 244.3 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

This vessel was made during the later phase of Paracas art (c. 400 B.C.E. into the first centuries of the common era) when flying figures became common in both ceramic and embroidered textile iconography, with many holding knives and heads in the same manner as this painted ceramic image.

Art historians have interpreted the figures in various ways—as spirits taking flight in the afterlife (linking them to the burial context of the art), or as representations of living humans in a state of trance during a ceremony. Many flyers, including the bowl’s flying Oculate Being, carry heads and accessories resembling knives, perhaps a reference to ferrying powerfully symbolic heads to another realm. Whatever their original meaning, these energized, animated beings certainly demonstrate the creativity and technical virtuosity of Paracas artists in all media.

Paracas ceramic trumpet showing a figure grasping a head and a falcon, c. 300–200 B.C.E., polychromed ceramic, Ocucaje-South Coast, Paracas, Peru, diameter of mouthpiece: 3.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)