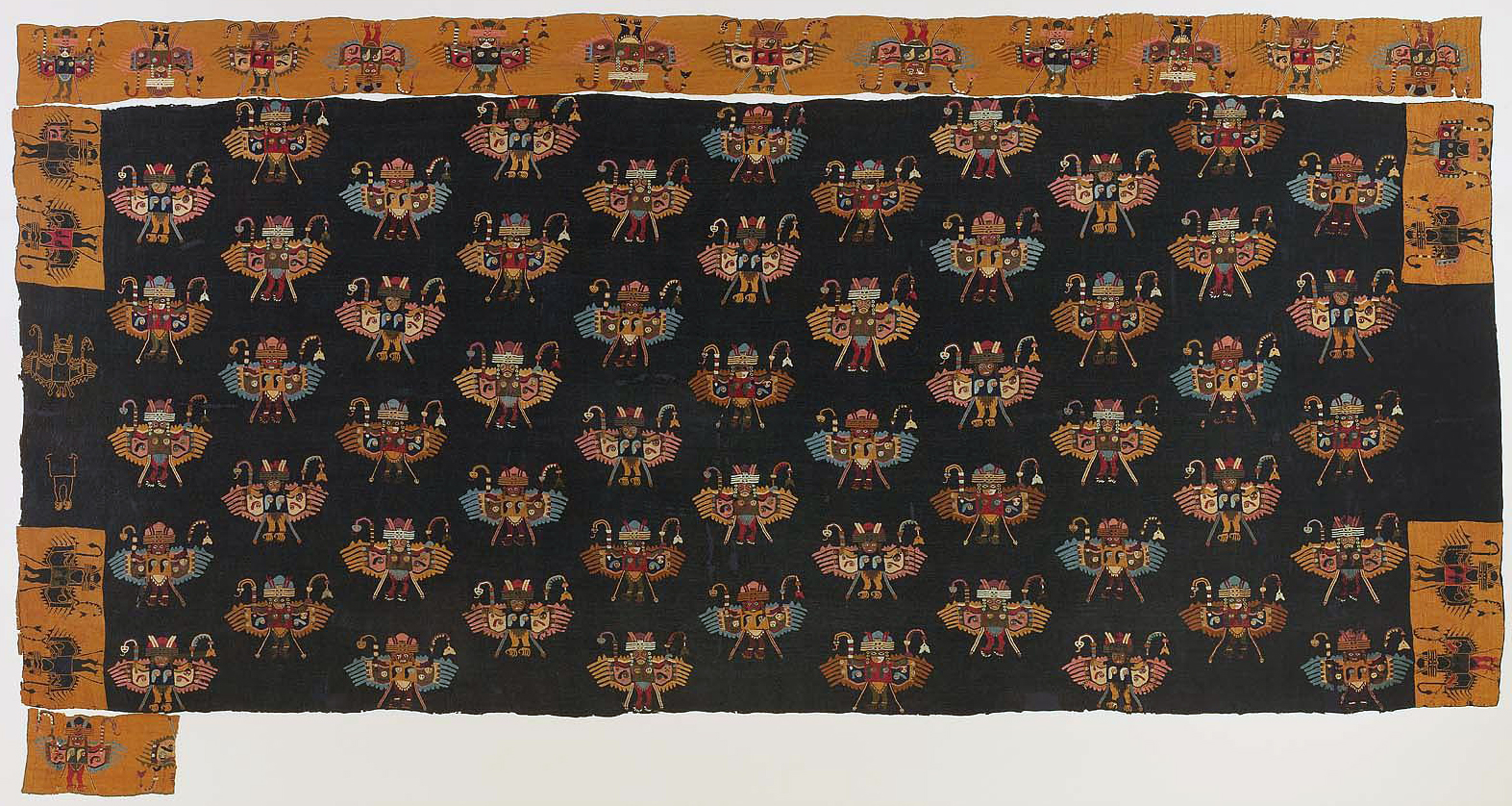

Man’s mantle and two border fragments, Paracas, 50–100 C.E., wool plain weave, embroidered with wool, 101 x 244.3 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The Transcendent Bird

Birds and winged creatures have often been tasked with duties of great symbolic importance in human culture. From harpies to storks, interfacing with the spirit realm and ferrying precious items and messages are just a few of birds’ mythic and folkloric roles throughout time and place. In the Peruvian south coast, a village culture now known as Paracas (c. 700 B.C.E. to 200 C.E.) created a version of the supernatural bird that demonstrates enduring elements of Andean art—a bird with outstretched wings, composite imagery, and symbolic heads—in a distinctively Paracas visual style.

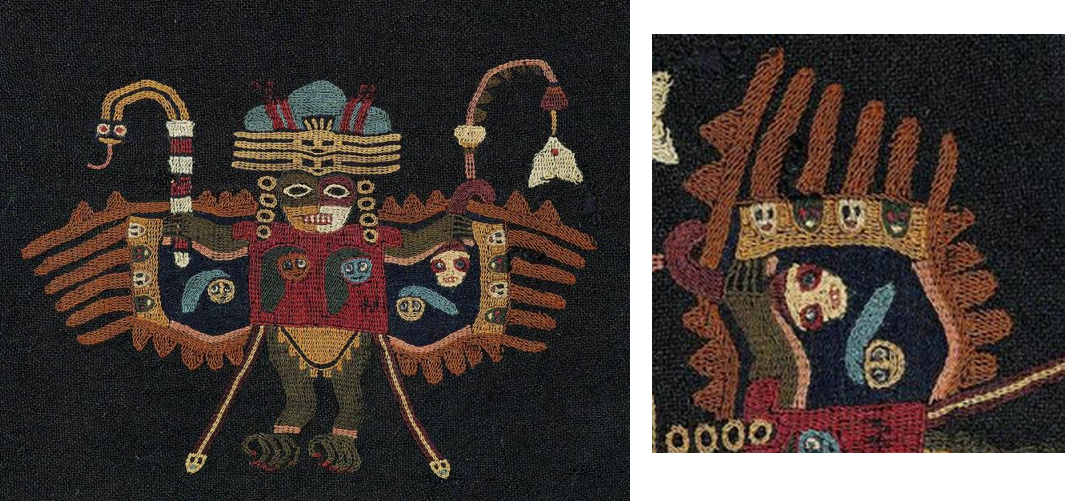

Detail, Man’s mantle and two border fragments, Paracas, 50–100 C.E., wool plain weave, embroidered with wool, 101 x 244.3 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

This being was recorded in embroidered camelid fiber upon a large funeral mantle, one layer of many textiles making up an elite mummy bundle preserved for some 2,000 years in the Paracas Necropolis cemetery on the arid coastal peninsula which gives the culture its name. When discovered and unwrapped, this textile (from the 1st century C.E.) revealed colorful, flying human/bird figures dressed in elaborate costume and possessing of an intriguing array of accessories.

Anatomy and Costume

The avian figures are rendered in the final stylistic phase of Paracas Necropolis embroidery that art historians refer to as the Block Color style. The placement of the figures in a checkerboard pattern across the mantle’s ground cloth and in alternating up/down poses on its border is typical of Block Color compositions. The inherent freedom of embroidery, a technique in which thread is stitched upon the surface of a woven cloth, made it possible for Paracas artists to create complex, multi-colored figures. Four different combinations of red, pink, blue, dark green, yellow, and soft green stitches articulate a headdress with frontal bands and dangling ornaments, colorful faces (possibly wearing masks), and fringed tunics. They carry banded staffs curving into serpents in one hand, curving staffs with fringe ending in floral or fishtail ornaments in another. Fantastical elements, such as avian toe-and-talon feet and snake emanations, place the figure firmly in the realm of the supernatural.

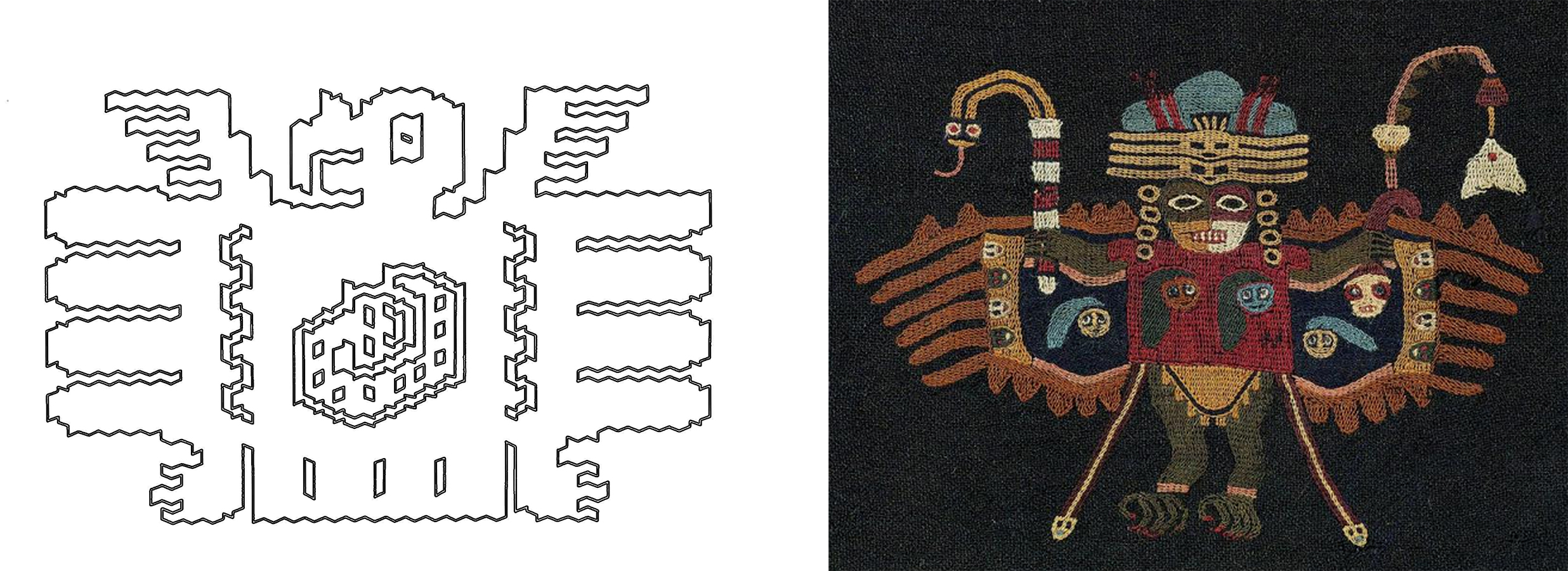

Left: design from a Huaca Prieta textile showing a condor with a serpent or fish in its stomach (redrawn from Bird, 1963); right: detail, Man’s mantle and two border fragments, Paracas, 50–100 C.E., wool plain weave, embroidered with wool, 101 x 244.3 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

While the color and curvilinear style are unprecedented in Andean art, serpent/bird combinations and composite imagery are found in Andean art as early as the Cotton Pre-Ceramic period (c. 3000 B.C.E.–1800 B.C.E.) in the Huaca Prieta twined textile and in stone at the Old Temple of Chavín de Huantar (c. 900 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E.). The Paracas human/bird’s wing feathers also double as heads, another example of characteristically Andean composite imagery.

The Symbolic Power of Heads

Figures clutch a head by its hair, two heads are placed on the front of the body, and one is placed within each wing. Heads are a frequent motif appearing in all phases of Paracas art, and caches of severed human heads have been found within some of their burials. Numerous archeologists, beginning with Julio C. Tello in the early 20th century, believed severed heads were trophies taken in conflict. This interpretation has been supported by the fact that many heads, some of young men, were buried with ropes (presumably for transport and display) still attached to their skulls.

Detail showing feather/heads, Man’s mantle and two border fragments, Paracas, 50–100 C.E., wool plain weave, embroidered with wool, 101 x 244.3 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Other heads were buried intact and wrapped in cotton cloth before burial, suggesting they were not trophies, but the heads of ancestral elders. Art historian Anne Paul observed that there are far more heads depicted in Paracas art than are actually found in burials, and there is little evidence to suggest that Paracas was a particularly aggressive culture. She believes the presence of so many heads in their art may be a stronger reflection of their symbolic power than a frequent practice of head collection.[1]

Ladder-tailed nightjar, Rio São Manuel, South Amazon, Brazil (photo: Charles J Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0)

These heads intersected with conceptions of birds in a number of ways. Birds may have been seen as aids in the act of headhunting (for those that were likely trophy heads), as vehicles for transporting them to the spirit world, and as mirrors of their ritual consumption. An association between the nightjar bird and decapitation is documented in narratives from village cultures of eastern Brazil.[2]

Left: Detail of a textile fragment with a head-tasting figure (circled in red), probably Paracas, 200–600 C.E., cotton and camelid fiber, 10 1/4 x 6 11/16 inches (Brooklyn Museum); right: Double spout-and-bridge vessel depicting a head-tasting bird deity, Nasca, 100 B.C.E.–600 C.E., ceramic (British Museum, London, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Some Paracas Block Color figures are shown with tongue-like appendages probing clutched heads, or small birds and other animals possibly substituting for heads.[3] Further, Paracans would have observed carrion-feeding birds such as Andean condors, who visited the coast, and the local turkey vultures consuming carcasses. These activities would have strongly resonated with their attunement to the cycle of life from death. As the Nasca culture (c. 100 C.E.–800 C.E.) arose to the south of the Paracas region, this imagery persisted in their art. One Nasca ceramic vessel very clearly depicts a winged supernatural with a headdress, masked face, avian feet, and faces within its wings; it is clutching and connected to a head by a shared mouth band.

Left: Turkey vultures, Paracas Reserve, Peru (photo: Dr. Mary Brown, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Andean condor, Arequipa, Peru (photo: Pedro Szekely, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Avian Ritual Performance

The fringed tunics, headdress ornaments, and staffs depicted on the figures illustrate actual found objects within certain mummy bundles, revealing that they are more than symbols, they reflect a number of items used in Paracas ritual life.

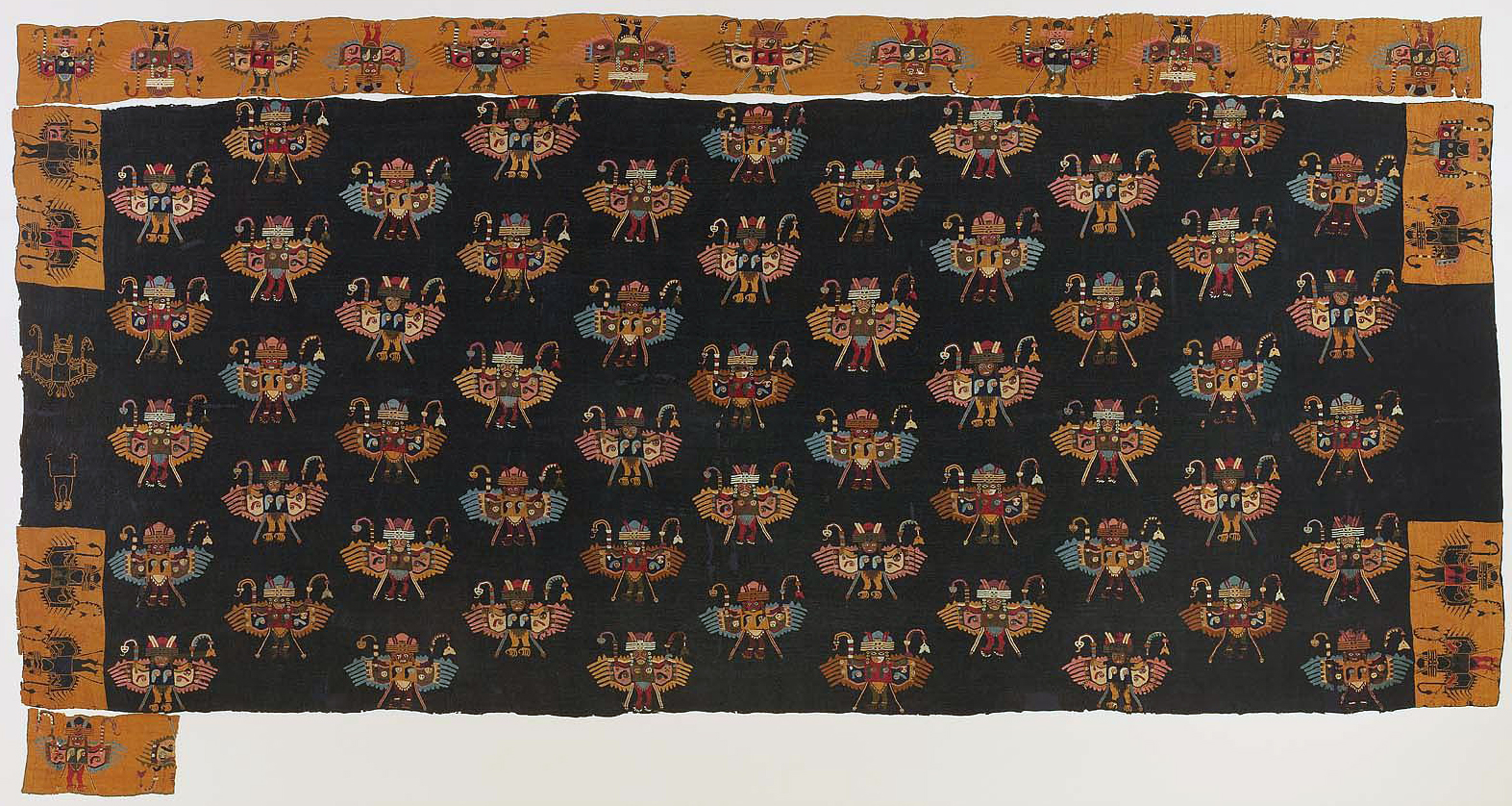

Detail, Man’s mantle and two border fragments, Paracas, 50–100 C.E., wool plain weave, embroidered with wool, 101 x 244.3 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Prior to the appearance of Paracas culture, there is very little evidence for the use of avian costume in the Andes. This imagery suggests that Paracas society may have been the first in the Andes to engage in avian-inspired ritual performance. These performances might have involved a state of trance during which an individual takes a psychological journey to another realm, generally to acquire knowledge and skills needed in the human world, often aided by an animal companion or symbolically becoming an animal in the process. As flyers and divers, birds are able to access realms unavailable to humans, and have thus been associated with ritual journeys and spiritual transformation worldwide. In the Andes, however, prior to Paracas culture the jaguar was the animal more closely associated with shamanic transformation, as demonstrated by the monumental stone art of highland Chavín culture.

Man’s mantle and two border fragments, Paracas, 50–100 C.E., wool plain weave, embroidered with wool, 101 x 244.3 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Reading the Mantle

These fantastical avian beings reveal noteworthy elements of Paracas cultural life: the symbolic role of birds, heads, and the possibility of avian-inspired rituals. The flying figures may be illustrations of humans who engaged in ritual performance during life and were believed to transform into supernatural birds in the afterlife. The mantle may have been created as an aid to this transformative process, helping to incubate an individual within a bundle so that he would emerge in the afterlife as a bird/human hybrid. The imagery demonstrates an ongoing Andean interest in birds, bodiless heads, composite visual systems, and the importance of the afterlife, expressed in a unique Paracas art style.