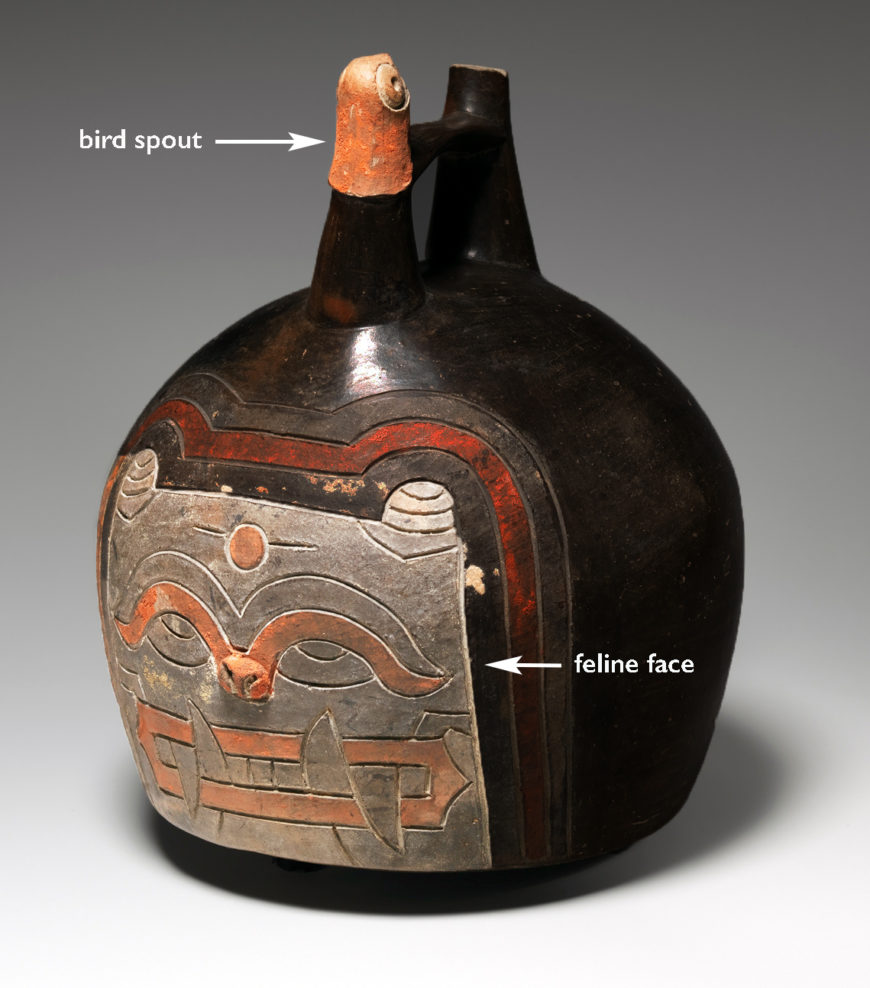

Feline Face Bottle, Paracas, 4th–3rd century B.C.E., ceramic and post-fired paint, 17.8 x 14.3 x 13.7 cm, from the Ica Valley, Peru (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

An animal face in clay

A feline with enormous fangs snarls on the front of an ancient Andean ceramic jar. Two spouts rise from the top, and a small bird’s head is lightly carved into one of them. The stories once told about the feline and bird are long lost to time, but the jar and its animals still communicate insights about the people who created them. In the absence of written texts, material culture such as this ceramic jar is the only surviving record of this ancient culture.

Feline face bottle (detail), Paracas, 4th–3rd century B.C.E., ceramic and post-fired paint, 17.8 x 14.3 x 13.7 cm, from the Ica Valley, Peru (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The jar is from the Paracas culture, a village society that thrived on the south coastal Peruvian desert during and just after the first millennium B.C.E. This vessel was found in the Ica Valley to the south of the Paracas peninsula.

The feline face was created by lines lightly carved into the soft, pre-fired clay surface, a technique called incising. After firing, the jar was colored with a resin paint, a distinctive Paracas technique. Colors, typically four or five but sometimes up to fifteen, were made of pigments and binders from the plants, minerals, and other materials available in the desert coast environment, including reptile urine. [1]

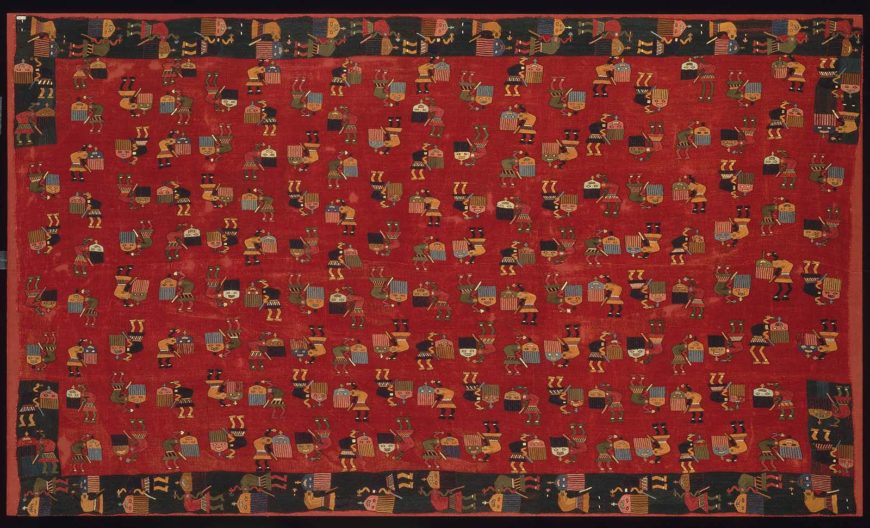

Embroidered textile found with a mummy bundle. Mantle, Peruvian (Paracas), 0-100 C.E., wool, plain weave, embroidered with wool, 142 x 241 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The jar’s survival can be credited to the culture’s reverence for their ancestors and concern with furnishing the realm of the afterlife. This resulted in the creation of mummy bundles (wrapping the dead in layers of textiles) and burying them with grave offerings in the arid Paracas peninsula and neighboring river valleys. The desert climate, the driest in the world, fortunately also preserved a large quantity of ancient textiles, fragile materials that are usually lost forever when buried.

Background: Chavín and its influence on Paracas

Examining the vessel’s technique, imagery, and style have revealed clues about cultural interactions between Paracas and another culture from the highland (mountainous) region, known as Chavín (pronounced Cha-VEEN). Comparing ceramics from the two cultures reveals how the Paracas ceramic tradition, once heavily influenced by Chavín, began to develop its own characteristics. One of the notable ways this occurred was by changing the style of a Chavín feline, among the most important highland animal images, and putting a bird on it.

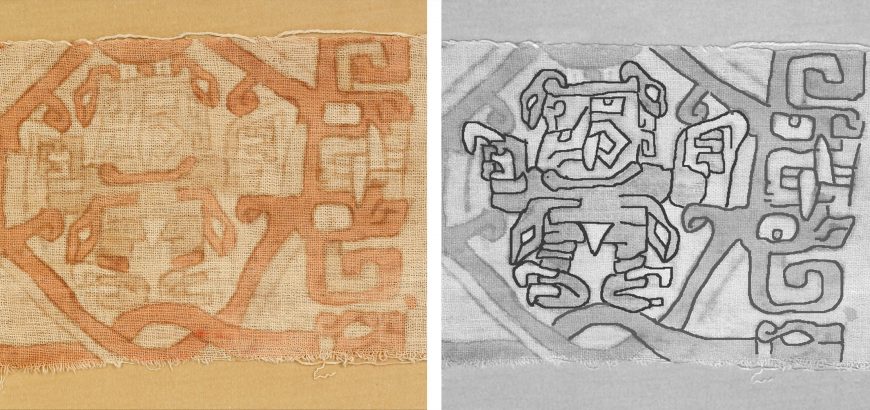

Textile fragment with the Staff God, 4th–3rd century B.C.E., Chavín culture, Peru, cotton, refined iron earth pigments, 14.6 x 31.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The highland culture of Chavín was one of the key cultures in the Early Horizon Andean interaction sphere (c. 900 B.C.E.–100 C.E.). Its influence is apparent in the highlands and the coast by the widespread use of a strikingly distinct visual art style. Chavín images are abstract and composite, with multiple animals appearing in one body, such as we see in a textile fragment showing the Staff God. Here, the Staff God is shown with its head in profile, with snakes emerging from the top of the head, a feline-fanged mouth, snake belt, and taloned hands and feet.

Animals in Chavín images often appear aggressive, with over-sized, interlocking fangs and long claws. The eyes feature pendant irises (where the iris hangs from the top of the eye), and an upturned, “push-face” nose resembling the features of certain canine breeds.

Due to contact with the Amazon rainforest on the eastern slopes of the Andes, their imagery also featured tropical animals such as the spotted jaguar, harpy eagle, and possibly a caiman (a small crocodilian). Jaguar images are particularly emblematic of Chavín art style, as they are typically shown with exaggerated, exposed incisor teeth that give the animals a permanently aggressive demeanor. The spotted jaguar is recognized in their art by large, concentric circles included on its body and on the bodies of hybrid feline/human/avian beings. The Chavín art style is best demonstrated by their stone carving tradition at the highland site of Chavín de Huantar, and was carried throughout the highlands and to the coast by way of portable arts such as textiles and ceramics.

Chavín ceramics (left) influenced early Paracan ceramic vessels (right). Left: Stirrup-Spout Vessel with Feline and Cactus, 900/200 B.C.E., Chavin, North Coast, ceramic, 26.7 × 17.8 cm (Art Institute of Chicago); right: Feline face bottle, Paracas, 800–100 B.C.E., ceramic and post-fired paint, from the Ica Valley, Peru, 19.2 cm high (Fowler Museum)

Chavín ceramics were mostly dark brown, red, or black in color. Flat-based, spherical vessels typically featured raised, sculptural imagery and handles in a horseshoe shape connected to a vertical spout, called a stirrup-spout. The earliest Paracas ceramic vessels show a marked Chavín influence, and they are believed to be some of the first appearances of Chavín art style in the region. In the image above, we see a Chavín vessel on the left and a Paracas vessel on the right. Both have flat bases, dark colors, stirrup-spouts, and felines with oversized, interlocking fangs in faces protruding from the surface of the vessel.

Feline face bottle, Paracas, 4th–3rd century B.C.E., ceramic and post-fired paint, 17.8 x 14.3 x 13.7 cm, from the Ica Valley, Peru (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Paracas innovations: new forms, colors, and a bird

The Paracas vessel at The Metropolitan Museum of Art demonstrates how new ideas were changing the way Chavín imagery was used in Paracas art. While the vessel body retains the dark tones characteristic of Chavín, it also shows a number of changes. Its base is slightly more rounded than earlier vessels.

The face is confined to the surface, except for the small protruding nose. Instead of a stirrup-spout, the vessel has two spouts connected by a handle, known as the double-spout-and-bridge. This handle will become characteristic of ceramics of this region in the centuries after Paracas.

Pampas cat (photo: ZooPro, CC BY-SA 3.0)

One spout on the Paracas vessel has been rendered as a rounded bird’s head, with large, round eyes and a dot for a pupil. Under the bird spout, the feline face retains the interlocking fangs of Chavín imagery that are seen in their ceramics and stone imagery; however, the irises hanging from the top of the eye have been softened to resemble an upward gaze. The eyes are crowned by curving brows that have lost the angry ferocity of Chavín prototypes.

The rounded ears have incised lines that might reference the stripes of a small, coastal pampas cat rather than the spotted jaguars depicted in the highlands. The design was originally colored by post-fire paint in bright white and red.

These changes will later give way to some vessels that are entirely in the shape of birds, with colorful, interlocking abstract bands and circles illustrating abstract, dappled wing feathers.

The Bird Whistle Spout

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s vessel, the Paracans connected sound to the bird’s head. The spout became a sound-maker when liquid was poured, as the fluid’s movement pushed the air inside through a whistle chamber. This effect animated the vessel and added to the sensory experience when it was put to use in a living ceremony, or conceptually in the afterlife. There is abundant material evidence of the importance of music in all areas of the Andes, from the earliest times through the conquest. Flutes made of bird bones were found in the ancient coastal site of Caral.

Shell trumpets appeared in highland Chavín. Ceramic trumpets, gourd rattles, and drums were in use throughout the south coast. Panpipes and whistles appeared on the north coast and throughout the pan-Andean Inka empire (among other instruments). The range of instruments and their extensive use indicate how music, with its ability to alter states of mind, helped create a bridge to the numinous (supernatural or divine forces) in Andean life.

Feline face bottle, Paracas, 4th–3rd century B.C.E., ceramic and post-fired paint, 17.8 x 14.3 x 13.7 cm, from the Ica Valley, Peru (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Lessons of the Feline Face Vessel

Ceramics were one of the principal ways Andean cultures recorded their ideas. Further, their techniques, imagery, and form—made possible by easily molded and incised surfaces—are all clues for better understanding cultural exchange and changes within a culture. In the early stages of their ceramic production, Paracans incorporated a foreign ceramic style and feline into their own ideology, yet ultimately modified the image to match both their unique art style and the new ideas emerging in Paracas culture. The bird spout and whistle are particularly notable Paracas innovations. This vessel helps underscore that in the latter part of the first millennium B.C.E., Paracas broke further away from a formerly dominant influence and would continue to develop along a more independent path.