View from the Semi-subterranean Court, Tiwanaku, Bolivia, 300–400 CE (photo: Danielle Pereira, CC BY 2.0)

From approximately 200 to 1100 C.E., Tiwanaku, near Lake Titicaca in present-day western Bolivia, was the center of a civilization whose influence spread as far as southern coastal Peru and northern Chile.

At its height, the site was home to up to 40,000 people and was centered around a ceremonial center featuring several monumental stone structures, including the Semi-subterranean Court, which is the oldest of these structures, and used for over 1,000 years before the decline of the Tiwanaku civilization.

The experience of entering this court is a bit like entering an architectural time capsule. All its various features are visual representations of the ways the site’s inhabitants drew on older local cultures, adopted those from afar, and created their own variations to establish a unique culture. It is a fascinating window into the worldview and religion of the inhabitants through the centuries.

View of Tiwanaku with the Semi-subterranean Court to the right, Tiwanaku, Bolivia, 300–400 CE (photo: Fellipe Cicconi, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Location

Like most large cities, Tiwanaku had a central “downtown” area where the largest and most important buildings and structures are located. It is most often referred to as the ceremonial core due to its placement at the center of the site and the identification of most of the buildings as sites for important religious and political ceremonies. These buildings were constructed over the course of the site’s history, and some which were not in current use were even partially taken apart so the stones could be used in newer ones.

By the time Tiwanaku began to decline as a state, the ceremonial core had numerous buildings, platforms, and courtyards, the largest and most important being the Semi-subterranean Court, the Kalasasaya and Putuni Complex (a combination of raised platforms and courtyards), the Akapana (a complicated mound structure believed to be a recreation of the Quimsachata mountains), and a later temple complex, the Pumapunku.

Structure and design

The Semi-subterranean Court is a square courtyard approximately ninety-one feet long and eighty-five feet wide, completely open to the sky. Its four stone walls were built approximately six feet down into the earth rather than upwards. Entered via a flight of steps worn down by centuries of use, the space gives the sense of standing at the boundary between the earth and the sky. This feeling is enhanced by fifty-seven large vertical stones extending out of the sunken space and serving as a bridge between the earth and the sky.

Mapping the sky

Foreground: vertical stones and walls of the Semi-subterranean Court, Tiwanaku, Bolivia, 300–400 CE (photo: twiga269 ॐ FEMEN, CC BY-NC 2.0)

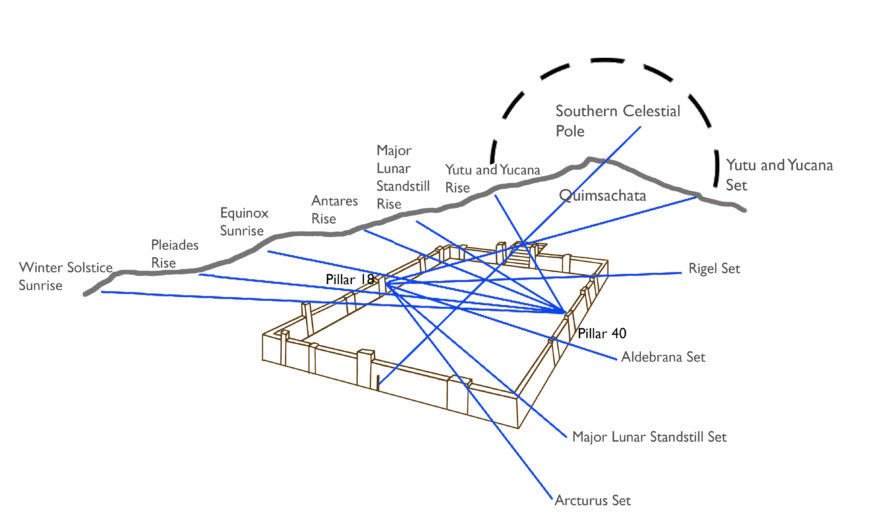

The central stones on three of the walls (north, east, and west) provide more than a physical connection to the sky above. They mark viewing points for various astronomical events such as solstice and equinox sunrises and sunsets, the rising and setting of important stars, and even point the way to the Celestial South Pole, the pivot of the southern hemisphere. The movements of the sun, moon, and stars across the sky regulated the rhythm of life in all Andean societies—used to determine when to plant and harvest crops and conduct religious rituals. As this court has been identified by archaeologists as a gathering place for these rituals, these stones would have helped participants properly orient themselves for the appropriate celestial event.

Astronomical alignments of the Semi-subterranean Court (redrawn after Vranich and Smith 2017, figure 6.4)

Connecting past and present

The Semi-subterranean Court served as a way in which the people of Tiwanaku could express their connections to past cultures while creating their own unique architectural and sculptural styles. Completed between 300–400 C.E., it is estimated to be the earliest monumental stone building constructed in the central ceremonial area.

The innovation of the Semi-subterranean Court begins with its size. The sunken court style of building is found in many of the archaeological sites which pre-date the founding of Tiwanaku in the regions surrounding Lake Titicaca such as Pucara and Chiripa, but the Semi-subterranean Court is the largest found to date. Its increased size was likely a statement of growing political power by the emerging Tiwanaku polity.

Tenon heads in a wall of the Semi-subterranean Court, Tiwanaku, Bolivia, 300–400 C.E. (photo: Phil, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The second, more striking change to the older sunken court style is the addition of the tenon heads (sculptures of heads which are set into a wall, anchored by a post called a tenon, but extend out from the surface) to all four walls in a pattern of repeating triangles between the large vertical stones.

Left: Common style of tenon head, Semi-subterranean Court, Tiwanaku, Bolivia (photo: THEOW, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0); right: Less common style of tenon head, Semi-subterranean Court, Tiwanaku, Bolivia (photo: Kevin Jones, CC BY 2.0)

The heads in the best condition display a wide range of variations on two basic compositions. The first and most common is a face with a wide band around the forehead, large deep-set eyes, a T-shaped rectangular nose, and an oval mouth with thick lips. The second, of which few uneroded examples remain, is a face without the forehead band, a more oval-shaped nose, and much smaller eyes. No two heads carved in either style are exactly alike: noses range from broad to narrow, the eyes can be circular or square, some mouths are wide open with clearly defined lips while others are tightly closed.

These are believed to represent the range of ethnicities or communities who were governed by the Tiwanaku polity and attended the ceremonies held in the court. It is still unknown if they were contributed by the groups they represent willingly or by force.

Sculpture and religion through time

Archaeological excavations from the mid-twentieth century uncovered several freestanding sculptures, two of which have compositions that provide a striking visual representation of the cultural changes which occurred in Tiwanaku society through the centuries.

Stela 15 is a four-sided rectangular stone shaft with simple low relief carving on all four sides. The narrower sides contain vertical patterns of snake-like figures running up towards several small mammals with long tails. Although both wider sides were each carved with the image of a large humanoid figure, erosion has virtually erased the carving on one. The other shows a standing figure with a large face containing the T-shaped nose, deep-set circular eyes, and oval mouth seen in some of the tenon heads. A beard-like band encircles the lower face, indicating that it is a male figure. The arm on the viewer’s left is placed diagonally above the one on the right, both raised above a band showing two opposing feline figures.

This imagery is associated with the Yayamama religious tradition that was practiced across the Lake Titicaca region beginning in 800 B.C.E. and declining around 300 C.E. The placement of Stela 15 in the Semi-subterranean Court indicates that, like the other sunken courtyards in considerably older Lake Titicaca sites, this structure was initially used for Yayamama ceremonies. The imagery of better-preserved stelae at other Yayamama sites suggest that some of these ceremonies centered around celebrating the fertility forces of the female-male duality (represented by deified ancestors) as well as those found throughout nature, represented by various animals and a navel-like image thought to represent the center of the cosmos.

Left: A drawing showing all four sides of a Yayamama stela from Taraco, Peru (redrawn after Chávez and Mohr Chávez 1988); right: Stele 15, Semi-subterranean Court, Tiwanaku, Bolivia (photo: Antoine 49, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

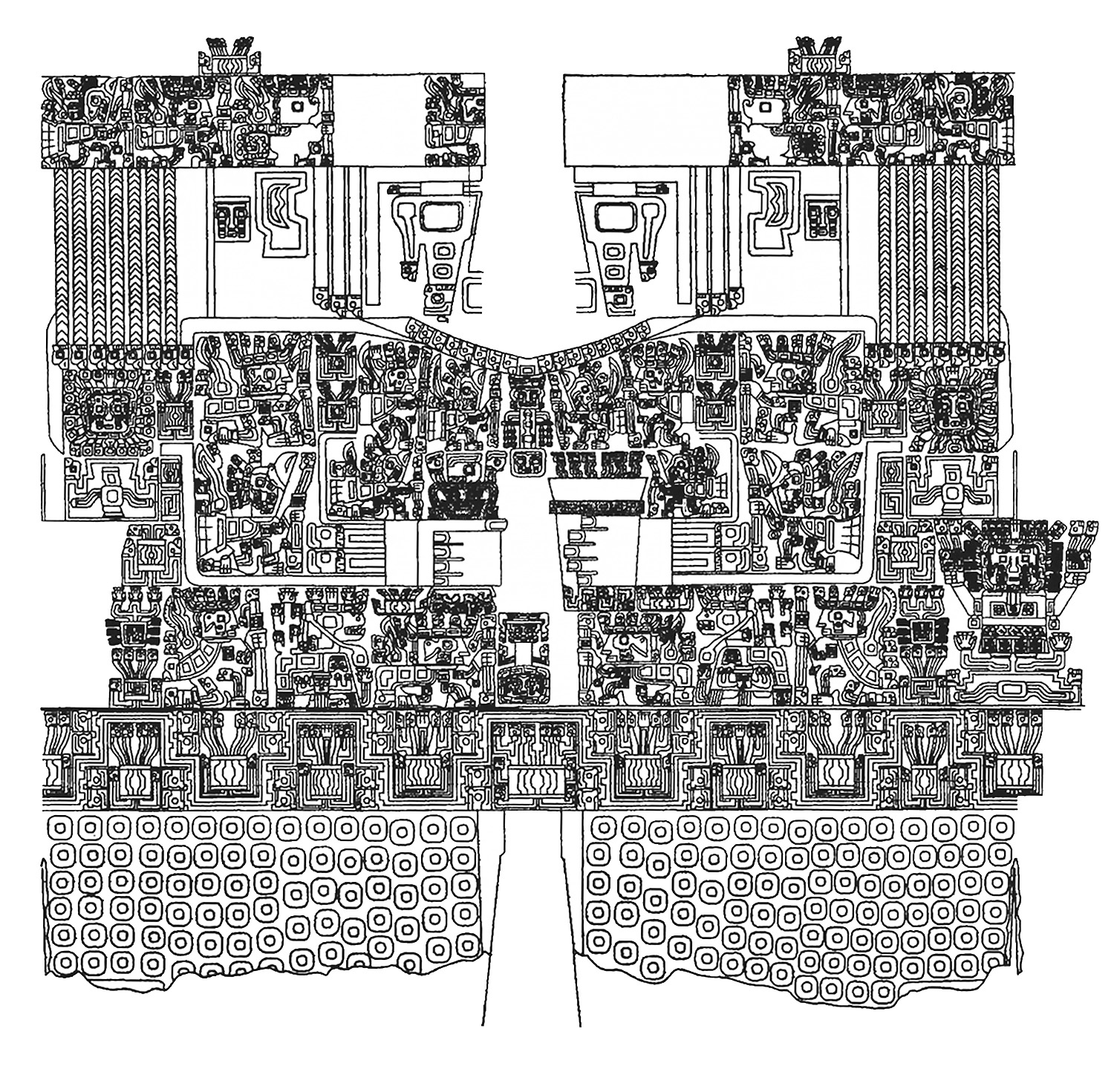

The wealth of realistic detail and iconography of the Bennett Monolith, built several centuries later, are the result of a dramatic change both in artistic styles and religious traditions. Here, the male figure (a towering twenty-four feet tall) is carved in the round and shown wearing elaborate clothing carved with extreme attention to detail. The figure’s torso and arms are covered with images of running bird-headed figures holding staffs and llamas sprouting sacred cacti. On the back there is also a rendition of the frontal-facing deity shown on the Sun Gate, identified by its large square face surrounded by rays ending in animal heads and circular shapes. Instead of holding two staffs, this version of the deity holds a flowering cactus plant in each hand.

The Bennett Monolith (photo: JoAnn Miller, CC BY 2.0)

In contrast to Stela 15, the figure depicted in the Bennett Monolith holds both arms against its sides with the hands facing forward rather than placed on top of each other. Like the deity of the Sun Gate, each hand holds an object, the left a cup similar in shape to a kero and the right a snuff tray used to ingest trance-inducing substances during ceremonies.

Drawing showing the carved decoration of the Bennett Monolith (redrawn after Posnansky 1945, Vol. II, Figs. 113 and 117)

The Bennett Monolith, with its references to Chavín de Huantar iconography, suggests that Tiwanaku gradually moved away from the Yayamama religious practices to those imported afar. Its presence in the Semi-subterranean Court, where it was originally placed near older sculptures like Stela 15, perfectly demonstrates how the inhabitants maintained ties with the past traditions of the Lake Titicaca region while continuing to innovate and adopt new ideas.

Overall, the Semi-Subterranean Court marks the rise of Tiwanaku’s importance as a regional center. Its large size, innovative architectural sculpture, and changing free-standing monuments demonstrate the inhabitants’ desire to create a unique version of the older regional culture and those from abroad to express their power and influence.