The Inka, like the Aztecs (or Mexica) of Mesoamerica, were relative newcomers to power at the time of European contact. When Francisco Pizarro took the Inka ruler (or Sapa Inka) Atahualpa hostage in 1532, the Inka empire had existed fewer than two centuries. Also like the Aztecs, the Inka had developed a complex culture deeply rooted in the traditions that came before them. Their textiles, ceramics, metal- and woodwork, and architecture all reflect the materials, environment, and cultural traditions of the Andes, as well as the power and ambitions of the Inka empire.

Along the Inka road system or Qhapaq Ñan today, Pucará del Aconquija, Argentina (photo: Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación Argentina, CC BY-SA 2.0)

An Empire of Roads—and Cords

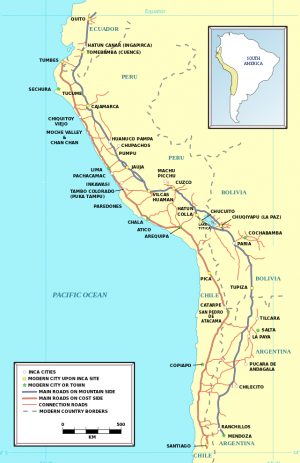

Map of the Qhapaq Ñan (Inka road system) (map: Manco Capac, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Inka empire at its greatest extent sprawled from the modern-day city of Quito in Ecuador to Santiago in Chile. The Inka called their empire Tawantinsuyu, usually translated as “Land of the Four Quarters” in their language, Quechua. At the center of the empire was the capital city of Cusco. The empire was connected by a road system—the Qhapaq Ñan—that was used for official Inka business only. Soldiers, officials, and llama caravans carrying food, ceramics, textiles, and other items used the roads, and so did message runners. These runners were stationed at regular intervals along the roads, so that messages could travel swiftly throughout the empire.

However, the messages that these runners carried were not written in the way we would expect. They were not made of marks on paper, stone, or clay. They were, instead, encoded into a knotted string implement called a quipu. Our knowledge of quipu remains limited. We have been able to determine only some of the ways that the quipu were used. Researchers continue to investigate this unique system of communication. The knots along the various cords recorded numbers, so that a knot with 5 loops could represent the number 5. The position on the cord could then determine what the number meant in a decimal system, so that a 5-loop knot could represent the number 5, or 50, or 500, and so forth.

The cords of quipus are frequently composed of different natural and dyed colors, but the reason or meaning behind those colors so far eludes scholars. The numbers encoded in the quipus helped the Inka keep track of the tax-paying obligations of their subjects, record population numbers, harvest yields, herds of livestock, and other important information. Also recorded on the quipu were stories—histories of the Inka and other social information. However, scholars today still don’t know how that information was encoded into the quipu.

More valuable than gold

Quipus and other Inka fiber objects were made from yarn spun from alpaca fibers. Llamas and alpacas are the domesticated relatives of the wild camelids of the Andes, the guanaco and vicuña, and all of them are related to the camel. Alpacas and llamas were important to the functioning of the Inka empire, but they had been essential to the lives of Andeans for millennia. Llamas provided meat as well as acting as beasts of burden—an adult male llama can carry up to 100 pounds. Alpacas provided soft, strong wool for textiles and rope-making.

All-T’oqapu Tunic, Inka, 1450–1540, camelid fiber and cotton, 90.2 x 77.15 cm (Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C.)

When the Spaniards encountered the Inka, they were confused by the fact that they considered textiles more valuable than gold. Textiles were integral to the structure of the Inka empire. Acllas, or “chosen women,” were kept in seclusion by the Inka to weave fine textiles (called qompi). These textiles mostly took the form of tunics and mantles. Some were distributed as high-status gifts by the Sapa Inka to cement the loyalty of local lords throughout the empire. Others were burned as sacrifices to Inti, the sun god and divine ancestor of the Inka ruling class. This shows us just how highly the Inka regarded textiles: they were fit for a god.

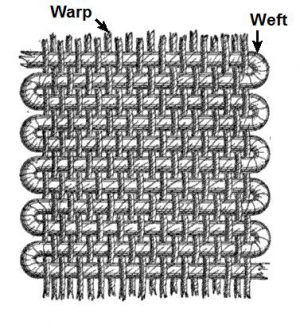

Diagram of warp and weft, (image: Ryj, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The acllas were not the only ones who wove. People of all ages spun, dyed, and wove textiles. The quality of wool, the fineness of its spinning, the relative rarity of the dye, and the skill of its weaving all determined the value of a textile. Some kinds of textiles were reserved for nobility or for warriors. The super-fine wool of wild guanacos and vicuñas was reserved only for the Sapa Inka’s garments.

A textile is created using a grid of warp (usually vertical) threads, which act as the support or skeleton of the fabric, and weft (usually horizontal) threads, which are passed under and over the warp threads. Where the weft threads cover the warp creates the surface design of the textile, somewhat like pixels in a computer image. The “pixel size” is determined by thread fineness. Decoration on Inka textiles was based in this grid structure, resulting in geometric designs.

Inka metalwork

Despite the value they placed on textiles, the Inka did also create works out of gold and silver, but unfortunately, most were melted down by the Spaniards for ease of transport, or destroyed because they were thought to be idols. Depictions of people, animals, and plants have survived. The plants tend to be quite naturalistic, while the people and animals are more abstracted. Human figures would likely originally have been dressed in miniature clothing. Figurines uncovered at the sites of human sacrifices on remote mountain peaks have been found dressed in finely-woven textiles with elaborate feather headdresses.

Left: Female figurine, 1400–1533, Inka, silver-gold alloy, 14.9 x 3.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Camelid figurine, 1400-1533, Inka, alloys of silver, gold and copper, 5.1 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Vessels for feasting

Ceramics were also important to the Inka empire. Large vessels were used to store foods such as corn and dried alpaca meat in warehouses along the Qhapaq Ñan, which could feed soldiers and imperial officials, or be distributed to the people in times of hardship. Big vessels could also be used to cook food and brew corn beer (asua or chicha) for feasting.

Storage jar or urpu, 15th–early 16th century, Inka, ceramic, 21.9 x 18.8 x 14.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Keru vessel, 15th–early 16th century, Inka, wood, 14.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Feasting (the ceremonial consumption of food and drink) was a method of cementing social and political ties, and the nobility were expected to provide feasts for large crowds on important occasions. Vessels called urpus were used for transport, storage, and asua-brewing. Some are over four feet tall. They have large handles on their sides and a thick protrusion from the base of the neck. A rope could be looped between the handles and over this protrusion, making it possible to carry on the back of a person or llama. The pointed base could be pushed into the ground to hold the vessel steady.

Asua would be drunk out of kerus, flared beakers made of wood, ceramic, or metal, depending on the status of the drinker. Kerus were often made in pairs, reflecting the social implications of drinking asua as a part of feasting. One keru from each pair would be larger than the other. The person of higher rank would drink from the larger keru and offer asua to the person of lower rank in the smaller vessel. By drinking together, they cemented the reciprocal obligations that required nobles to provide asua and food to the people, and those below them to provide taxes and loyalty to the rulers of the empire. The keru shown here is made from wood, and like the urpu vessel, has geometric designs.

Inka architecture

Perhaps the most well-known Inka art is their architecture. The Inka built everywhere they conquered, and their architectural style helped mark areas as belonging to the empire. Inka architecture is based on stone walls, fitted together in a very distinctive way. Instead of cutting stones into blocks and then laying those blocks together in rows, in some cases, the Inka would fit individual stones of varying sizes and shapes against each other, fitting them together like a puzzle. The stones would fit so closely that the Spanish remarked that a person could not even insert a knife blade between them.

Each stone was shaped so that it had a slight bulge or a slight indentation on the side where it would lay against another block. These bulges and indentations would slot together, holding the stones in place. It also allowed the stones to shift if they needed to—and they did need to, because Peru is seismically active and has frequent earthquakes.

Stone doorways, Qoricancha, Cusco (photo: Jean Robert Thibault, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The doorways, windows, and niches placed in Inka walls have a signature vertical trapezoid shape, a recognizable and distinctive aspect of their architecture. Sometimes referred to as a keyhole shape, it is thought that this form is also something that helps stabilize the architecture during earthquakes. The roofs of these buildings were made of wood and thatch.

The terraces of Ollantaytambo, Peru (photo: Ivan Mlinaric, CC BY 2.0)

The Inka also built large architectural ensembles like the site of Ollantaytambo, which was a waystation along the Qhapaq Ñan. It consisted of storehouses, living quarters, and a series of terraces built into the side of a mountain. In most cases, the Inka used terraces as a way to stabilize mountainside soil for farming, but at Ollantaytambo they were planted solely with flowers—a show of the empire’s power through its ability to use stone, manpower, and water to do nothing but create a lavish and pleasant leisure space.

Inka traditions survive

With their defeat at the hands of the Spaniards, the Inka lost their place as divinely-descended leaders of their people. However, Inka nobles petitioned for and often won the right to be treated as elites in colonial Spanish society, and celebrated their heritage at Christian festivals, such as Corpus Christi. The privileges the nobles received did not translate to the rest of the population, though, and many people were deprived of their lands and personal freedom, required to pay taxes through often arduous labor.

Rebellions vying for a return to Inka rule occurred throughout the colonial period, the last of which took place in the 1780s. Peru finally achieved independence from Spanish rule in the 1820s, establishing a republican government. Modern residents of Cusco and its surrounding areas are still proud of their Inka heritage, and modern religious celebrations often incorporate parts of native culture into Christian practices.

Additional resources:

Qhapaq Ñan UNESCO World Heritage Site page

Dualism in Andean Art from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire from the Smithsonian