Artist currently unknown, Crowned Nun Portrait of Sor María de Guadalupe (detail), c. 1800, oil on canvas (Banamex collection, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

One of the most famous types of female portraits in the colonial Spanish Americas are the monjas coronadas, or crowned nuns, so named for the elaborate floral crowns atop their heads. In these portraits, nuns are accompanied by objects such as candles, religious badges (escudos), a ring, dolls, flowers, and crowns. These portraits were made on the occasion of a nun’s profession (literally when she took the veil to officially enter a convent as a professed nun). Why were such lavish portraits of nuns created on the occasion of their profession, and who were they for? To answer this question, this essay looks at a few portraits from the viceroyalty of New Spain.

Convent church of Santa Catalina (painted yellow), Puebla, Mexico

Nuns in New Spain

In New Spain there were 52 convents (22 in Mexico City, 11 in Puebla, 5 in Oaxaca, with the others distributed across the viceroyalty). The first female religious order to appear in the Spanish colony was the Conceptionists, but eventually there were Carmelites, Poor Clares, Jeronymites, Ursulines, Recollect Augustinians, and Capuchins. Nuns were understood to be integral to the health of society since they prayed on behalf of people to help shorten sinners’ time in Purgatory. Nuns lived cloistered in a convent, meaning that once they entered they did not leave (except perhaps on the occasion of creating another convent somewhere else). The four main objectives of a nun’s life were chastity, obedience, enclosure, and poverty (at least for some nuns).

Grills inside the convent church of the ex-convent of Santa Mónica, Puebla

The actual space of the convent, and the nuns who lived within it, became important symbols in urban spaces and emblems of civic pride. A church was often connected to a convent; while nuns did not enter it, their presence could be heard or sensed through a grill that lay people could observe while in church.

José de Alcíbar, Sor María Ignacia de la Sangre de Cristo, 1777, oil on canvas, 180 x 190 cm (Museo Nacional de Historia, Mexico City)

Artist currently unknown, Sor Magdalena de Cristo, 1732, oil on canvas, (Museo ex-convento de Santa Mónica, Puebla; photo: Luisalvaz, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Nuns became increasingly important in the 17th and 18th centuries, and this is reflected in the increase in female religious orders, convent buildings, and objects associated with them. It is likely that the injection of silver into the economy from local silver mines meant more families acquired wealth, allowing them to pay the dowry needed to permit their daughters entry into a convent. A marriage dowry was more expensive than one needed for a convent, so becoming a nun was often a beneficial alternative for young women of elite families. While nuns might never see their families again, many could live a life of comfort inside the convent. Some orders, like the Conceptionists, had servants, could play music, and had libraries. The famous nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz had a large, exceptional library and scientific instruments at her disposal. It was primarily the wealthy orders for which the monjas coronadas were painted—many of them produced by the most famous artists of the day. This genre of portraiture began in the 18th century and continued into the early 19th century. There are also portraits of crowned nuns painted on the occasion of their death.

Artist currently unknown, Sor María Antonia de la Purísima Concepción Gil de Estrada y Arrillaga, c. 1777, oil on canvas, 81 x 105 cm (Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Mexico)

Portraits of crowned nuns

Artist currently unknown, escudo de monja with the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, 18th century, Oil on copper with tortoise frame, 5.9 cm in diameter (San Antonio Museum of Art)

In a portrait of Sor Madre Maria Antonia de la Purísima Concepción, the young nun looks out towards us. She wears the long blue mantle associated with the Conceptionist order (which was supposed to mimic the Virgin Mary’s blue mantle). Her white blouse is crimped into pleats, which was time consuming—suggesting the importance of this moment in a nun’s life. Fastening her habit is a circular disc, called an escudo de monja. Her religious badge (most of which were painted on copper and were often in a tortoiseshell frame) shows the Virgin of Guadalupe on it, surrounded by saints. It was common for the escudo to show Marian imagery (imagery related to the Virgin Mary), most often the subject of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception. Nuns were meant to model themselves on Mary and to also become the spiritual brides of Christ. Nuns were required to be chaste and pure (virginal), as Mary was.

Artist currently unknown, Sor María Antonia de la Purísima Concepción Gil de Estrada y Arrillaga, c. 1777, oil on canvas, 81 x 105 cm (Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Mexico)

Sor (Sister) María also holds in her right hand a doll of the Christ Child, elaborately dressed, and in her left hand she holds a floral bouquet (which includes a heart, within which is the Christ Child). In other portraits, nuns might carry a candle decorated with flowers and jewels. Atop her head, she wears a black veil embroidered with gold and an ornate floral crown. The flowers were often made of wax or fabric.

José de Alcíbar, Madre María Ana Josefa de Señor San Ignacio, 1795, oil canvas, 104 x 84 cm (Szépmüvészeti Múzeum/Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest)

Nuns also often wore a ring on one of their fingers. Many of these objects represent the actual objects used in the profession ceremony when a nun took her vows as a bride of Christ. The ring, for instance, symbolizes a nun’s mystical marriage to Christ, and the floral crown signifies the glory of immortality won by female chastity and thus relates to a nun’s virginal status. Interestingly, the statue of the Christ Child suggests that the nun will perform the role of a “mother”—she is at once bride to Christ and caretaker of his young self.

Artist currently unknown, Crowned Nun Portrait of Sor María de Guadalupe, c. 1800, oil on canvas (Banamex collection, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Patrons and viewers

Nuns themselves were not typically the viewers of their own portraits, so these images did not serve as models for their behavior after entering convent walls. Portraits of crowned nuns were typically commissioned by a nun’s family as a last act of vanity before their daughter joined the convent. The extravagant clothing and paraphernalia would have been costly, and a portrait like this advertised a family’ wealth.

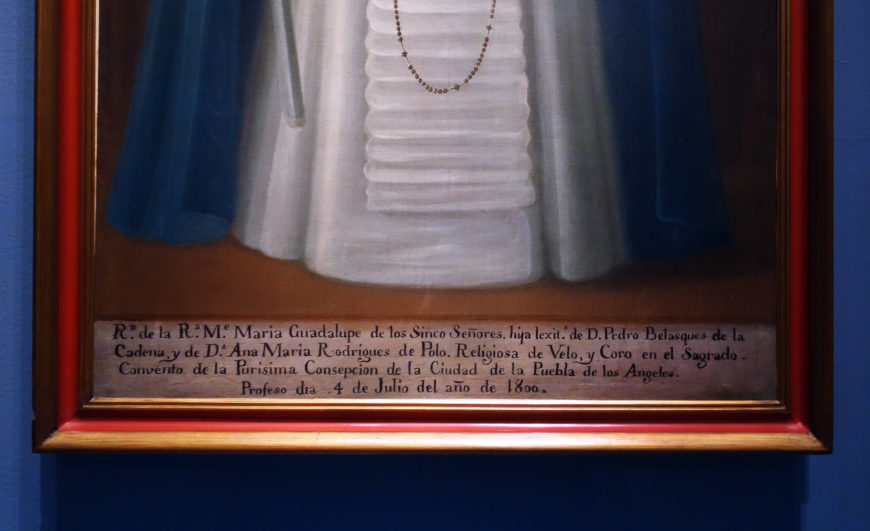

Inscription with details of the nun’s lineage and profession details. Artist currently unknown, Crowned Nun Portrait of Sor María de Guadalupe, c. 1800, oil on canvas (Banamex collection, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

These representations also functioned as official documents recounting their daughter’s lineage. They often include lengthy inscriptions noting the name of the recently professed nun, her parents’ names (and that she is their legitimate daughter), the date of her profession, the name of the convent that she entered, and sometimes the date of her death. In a portrait of Sor María de Guadalupe, the inscription at the bottom of the painting lists her name, that she is the legitimate daughter of Don Pedro Belasquez de la Candena and Doña Ana Maria Rodgrigues de Polo. It also notes that she was a nun in the Convent of the Immaculate Conception in the city of Puebla, and that she professed on July 4, 1800.

Nuns’ portraits did not only serve as biographical documentation and a memento for the young woman’s family. They also functioned as potent symbols that these sitters were performing a necessary duty to the community at large: they prayed for the broader community’s redemption and salvation. Additionally, the crowned nuns reminded viewers that the sitters, by remaining pure and virginal in an enclosed paradise (the convent), became new Eves to populate a Garden of Eden. Such messages increased a family’s social status because in such a painting their daughter was shown forever performing her role as a faithful, chaste bride of Christ who aided in the salvation of New Spain’s population.

Additional resources:

Watch a video about a nun portrait

Virginia Armella de Aspe, and Guillermo Tovar de Teresa, Escudos de monjas novohispanas (Mexico City: Gusto, 1993)

James M. Córdova, The Art of Professing in Bourbon Mexico: Crowned-Nun Portraits and Reform in the Convent (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014)

Martha J. Egan, “Escudos de monjas: Religious miniatures of New Spain,” Latin American Art Magazine, Inc. 5, no. 4 (1994).

Kirsten Hammer, “Monjas coronadas: The Crowned Nuns of Viceregal Mexico” in Retratos: 2,000 Years of Latin American Portraits, ed. Elizabeth P. Benson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004)

Monjas coronadas: vida conventual femenina en Hispanoamérica (Mexico City: Concaculta, 2003)